From India's hope to 'political poison': How the Economist has covered Modi since 2014

The publication didn't back Narendra Modi for prime minister, but agreed that he might do great things for India's economy.

"Intolerant India". That's the latest cover of the Economist, the issue dated January 25, 2020, and devoted to decoding how Narendra Modi "stokes divisions in the world’s biggest democracy".

"Alas, what has been electoral nectar for the BJP is political poison for India," the story says. "By undermining the secular principles of the constitution, Mr Modi’s latest initiatives threaten to do damage to India’s democracy that could last for decades. They are also likely to lead to bloodshed."

A separate piece says Modi has "taken his gloves off" after winning the Lok Sabha election in May 2019. "Yet even if Mr Modi and Mr Shah do get their way, and if India’s Supreme Court overlooks the plainly contentious aspects of the CAA, the costs of the citizenship row to Mr Modi and his country are high. From a financial perspective, the outlays would be prohibitive even if India’s economy had not slowed in the past year to its lowest level of growth in four decades."

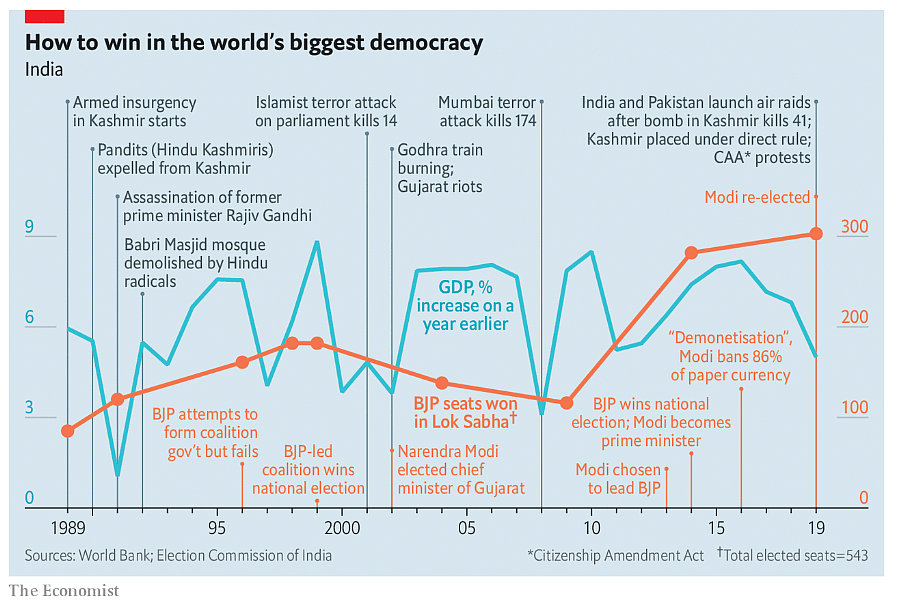

The piece, which says Modi has "united a broad coalition against him", also has this helpful graph.

The magazine's cover story comes days after it released its annual Democracy Index for 2019, on which India dropped 10 places. India's rank was also the lowest on record since the Economist began compiling this data in 2006.

The Economist has always been cautious about Modi while lauding his focus on "growth".

In its issue dated April 5, 2014, when the BJP was poised to win the Lok Sabha election, the Economist said it "cannot bring itself to back Mr Modi for India’s highest office".

It cited the "Hindu rampage against Muslims in Gujarat in 2002", calling it an "orgy of murder and rape", and how Modi "helped organise a march...to Ayodhya" in the 1990s, along with his speeches that "shamelessly whipped up Hindus against Muslims".

The piece minced no words: "But for now he should be judged on his record — which is that of a man who is still associated with sectarian hatred. There is nothing modern, honest or fair about that. India deserves better."

Yet when Modi won a few weeks later, the Economist said his victory "gives India its best chance ever of prosperity".

"Now, for the first time ever, India has a strong government whose priority is growth. Narendra Modi, who leads the Bharatiya Janata Party, has won a tremendous victory on the strength of promising to make India’s economy work. Although we did not endorse him, because we believe that he has not atoned sufficiently for the massacre of Muslims that took place in Gujarat while he was chief minister, we wish him every success: an Indian growth miracle would be a great thing not just for Indians, but also for the world."

Its February 19, 2015, cover was devoted to India's economy, saying it needs "more than a lick of paint".

Yet it remained hopeful in a second piece: "If India could only take wing it would become the global economy’s high-flyer — but to do so it must shed the legacy of counter-productive policy...Mr Modi and Mr Jaitley have a rare chance to turbocharge an Indian take-off. They must not waste it."

Its May 23, 2015, issue took a deep dive into Modi's politics and policies. "Sit with him and you come away impressed by an intensely driven outsider determined to leave his mark on national affairs. He can sound arrogant, vainglorious or hubristic. More than any Indian prime minister since Indira Gandhi, he personally embodies power."

But, "The big worry about Mr Modi is his history of allowing, and exploiting, disharmony. In Gujarat pogroms on his watch in 2002 killed over 1,000, two-thirds from the small Muslim population, as police stood by. After that Mr Modi campaigned for election by stirring more hostility to Muslims, saying they had too many children. Gujarat has otherwise remained calm, but is more polarised than most of India."

Then came demonetisation in 2016, and the Economist was not impressed. Modi returned to its cover on June 24, 2017, where demonetisation was criticised as "counterproductive, hamstringing legitimate businesses without doing much harm to illicit ones. No wonder the economy is starting to drag."

The piece continued: "India’s prime minister, in short, is not the radical reformer he is cracked up to be. He is more energetic than his predecessor, the stately Manmohan Singh, launching glitzy initiatives on everything from manufacturing to toilet-construction. But he has not come up with many big new ideas of his own..."

It also said Modi is more of a "chauvinist than an economist".

Modi only returned to the Economist's cover nearly two years later, after the February 2019 attack in Pulwama. "In the long run, stability depends on Pakistan ending its indefensible support for terrorism...But in the short run Mr Modi shares the responsibility to stop a disastrous escalation. Because he faces an election in April, he faces the hardest and most consequential calculations. They could come to define his premiership."

If Modi's on the cover, can a piece on Hindu nationalism be far behind? This issue had a story on "orange evolution" and the "struggle for India’s soul". "Under Mr Modi, the project to convert India into a fully fledged Hindu nation has moved ahead smartly...how far would Mr Modi be able to push the Hindutva project, even if he does get a new mandate? And if he loses, can a secular India be rebuilt?"

The latest issue minces no words on Modi's politics, even quoting a "seasoned politician who compares Modi's era to a "Second Reich".