Are top Indian newspapers complying with guidelines on suicide reporting?

The coverage of suicide in the English print media lacks compliance with globally accepted norms.

In September 2019, the Press Council of India, led by Justice CK Prasad, adopted guidelines for suicide reportage. Based on a combination of standards set by the World Health Organization and global best practices, it set norms for newspapers and news agencies to follow.

However, assessing the effectiveness of the guidelines yielded mixed results, with experts suggesting measures to better augment the role of the press in suicide prevention.

According to recommendations put forth by the WHO and the International Association for Suicide Prevention, media professionals must avoid the following: language which sensationalises or normalizes suicides; prominent placement and undue repetition of stories about suicide; explicit description of the method and the suicide note used; and detailed information about the site of a completed or attempted suicide.

The recommendations specify that the media should educate the public about suicide, word headlines carefully, exercise caution in using photographs, take particular care in reporting celebrity suicides, provide information about where to seek help, show consideration for the bereaved, and recognise that mediapersons themselves may be affected by stories about suicide.

These recommendations are based on the accepted policy of sensitive coverage being an essential aspect of suicide prevention strategies.

The Press Council’s guidelines state that the media “must not place stories about suicide prominently and unduly repeat such stories; use language which sensationalises or normalises suicide or presents it as a constructive solution to problems; explicitly describe the method used; provide details about the site; use sensational headlines; use photographs, video footage, or social media links”.

In India, 1,34,516 suicides were reported in 2018, as per the National Crime Records Bureau. Maharashtra had the highest number of suicides (17,972) followed by Tamil Nadu (13,896). The rate of suicide, per 1,00,000 people, was the highest in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (41.0) followed by Puducherry (33.8). Family problems and illnesses were reported as the major causes for suicides, followed by marriage related issues and drug abuse.

Given these statistics, how have national newspapers fared in their coverage of suicide in the context of the Press Council’s guidelines?

Some hits, many misses

We looked at over 25 articles each from the Times of India, Hindustan Times, Indian Express, Telegraph, New Indian Express and Hindu, from September 2019 to April 2020, to base our inferences. In case of four of these dailies, suicide-coverage norms were breached in varying extents.

The country’s most widely read English daily, The Times of India, was found to be in violation of the spirit of the Press Council’s guidelines. While the paper maintained compliance and uniformity in terms of the use of representational images in the stories, in some cases these arguably dramatised and glamourised the incident, something that norms issued by the IASP and others have cautioned against.

Additionally, it tended to report the method and items used in a little too much detail. Where suicide stemmed from family troubles or financial constraints, the stories contextualised the justification for the victim’s actions.

For instance, a report dated April 4, 2020, read: “Police said he had an argument with his wife following which he hanged himself from the ceiling fan using a dupatta.” Another dated March 25 read: “A 34-year-old businessman from Tirupur committed suicide by jumping off the sixth floor of a hotel on the Avinashi Road in Coimbatore on Tuesday due to losses he suffered in business.”

Specifically, when stories were centred around urban areas or involved officials in administrative posts, circumstances of family as well as tools used for hanging or shooting oneself were dealt with at length.

The Indian Express specifically violated the “method” guideline most of the time, going into details such as the floor the person had jumped from, or the metro train in front of which the individual leaped.

A report from Vadodara on February 1, 2020 specified the floor from which someone jumped and described his last moments as he entered the building. In the same report, a case of a runaway girl hanging from a tree was mentioned. Going by the recommendations, what is problematic here is the mention of the exact floor and the place of hanging.

Some pieces, even though written formally, explained suicide as a means to escape debt. For example, a story from Ludhiana dated October 29, 2019, read: “While two bodies were found hanging from grills in the lobby, the third was found hanging in a room from the ceiling fan. Police said that in an eight-page suicide note, the brothers had blamed two financiers of duping them of Rs 1 crore.” In stating facts, this particular instance presents the suicide as a solution to their financial woes - a violation of guidelines.

The strapline of a report dated November 8, 2019, which also carried details of the suicide note, read: “...the man claimed that he took the extreme step as he was in debt and due to harassment from loan and credit card recovery agents.”

About suicides in urban apartment complexes, the reports described the method and the condition the bodies were found in.

Unlike other dailies, the Hindu, at the end of almost every article about suicides, lists helpline numbers. While its reporting is more responsible than others surveyed, it did sensationalise suicides in a couple of articles. In a report dated March 29, 2020, where a man attempted suicide and survived, the incident was referred to as “high drama” and an “episode” — words that paint an exaggerated picture in the reader’s head.

This is attested to by a joint study on how the Indian media reports on suicides. There’s a tendency to “oversimplify” the reasons for suicide which, the study said, might normalise it for those with fragile mental health.

Reporting, in this regard, by the New Indian Express was occasionally irresponsible. According to international recommendations, the exact content of suicide notes is not to be shared by the media.

The New Indian Express did not always follow this. In many cases, it described the methods used for suicide, going against the WHO’s recommendations.

In a report dated February 18, 2020, when a playback singer killed herself in Bengaluru, the story was sensationalised. Towards the end of the story, under a subheading, “What she texted her family”, the newspaper reproduced the text messages she had sent her family before killing herself.

What industry veterans and experts say

Only recently has the gravity of sensitising the press to suicide come to the forefront. In 2018, journalist N Ram asked why Indian media houses “fail to comply with elementary norms of responsible suicide reporting”. Last year, a change.org petition urged NDTV to adopt the WHO’s guidelines while reporting on suicide.

A few years ago, the Hindu instructed its reporters to refrain from mentioning the method used for suicide.

“If a man hangs himself, we won’t say that, we will say that the man killed himself,” said Gautam Mengle, a crime reporter with the newspaper in Mumbai. “We’ll say something that vaguely hints at what has happened, but won’t be specific. The assumption is that describing the method might give ideas to someone reading the story, who is in a similar state of mind.”

Copycat suicides are a real phenomenon. The resource manual published by the WHO and the IASP says that 50 investigations into imitative suicides have been conducted. Reviews of these studies draw the same conclusion: that media reporting can lead to imitative suicidal behaviours. In some cases, this imitation is more evident than others. It peaks within the first three days and levels off by about two weeks, but can last longer sometimes, according to the report.

“Earlier, we had to find which helplines were working and then compile them to be added to articles. Now, the desk has a readymade graphic of the helplines they just have to add to the story,” said Mengle. The reporters are required to periodically make sure the helplines are functioning and if they are not, find the ones that are.

Mengle emphasised the need to pay attention to the words one uses in news reports. “If someone is/was treated for depression, we have to say that this person is being treated for clinical depression — not that they were suffering from depression.”

He said that suicide notes are put in news reports when they are very crucial to a story. “This is not just to grab eyeballs, but because it is abetment to suicide, which is a serious crime,” he said. “We cover suicides as incidents, but we haven’t covered it as an issue as much as we should.”

According to Lakshmi Narasimhan, a senior team member of the Banyan, an NGO advocating mental health in Chennai, it is necessary to train journalists to report sensitively on such cases on a large scale.

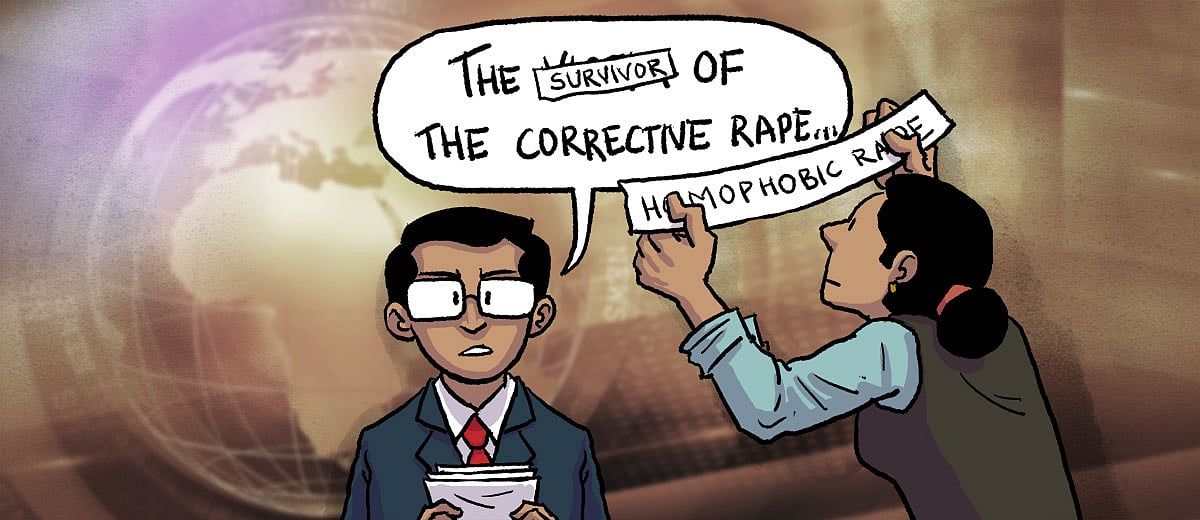

“Sometimes, certain kinds of reporting can trigger feelings in others. Also, one does not want to sensationalise or criminalise it in any way,” she said. “Suicide is not an offence. ‘Committed suicide’ is a phrase that is [wrongly] used quite often, and in that sense, I do think there is a long way to go.”

Narasimhan said that while not all media outlets cover suicides in the same manner, coverage that doesn’t comply with guidelines is predominant in the mainstream media.

“There’s a shift in attitude we need to see. It requires far more dissemination that what we are seeing right now, in terms of journalists understanding suicide and why it needs to be covered in a particular way,” she said.

A former crime reporter with the Free Press Journal and the Mumbai Mirror said there were no formal guidelines on reporting suicide at either organisation when she worked for them a few years ago.

Tabloids are guilty of sensationalising suicides more than broadsheets. “They don’t refrain from putting suicide stories as cover stories; sensationalism is a big factor,” said the reporter, on the condition of anonymity. The Mumbai Mirror has repeatedly run stories about suicides as the cover story.

“It’s really unfortunate how we have to find a sensational angle even when families of the deceased are grieving,” she said. “Sometimes, we had pictures but would refrain from using them, especially if the person was a minor. Also if the person survives, we try to keep the identity anonymous as they have a second chance at life.”

Two NGOs advocating mental health, the Schizophrenia Research Foundation and Sangath, have initiated a course that sensitises journalists on reporting on mental health. According to a lesson in the course, the link between mental illnesses, negativity, shame and violence is promoted by the entertainment industry and news media. The media very rarely covers stories of people who have improved with treatment and recovered.

Mohan Sinha, the former news editor of Hindustan Times, said even before formal instructions came, certain guidelines were implicit in the paper’s editorial policy on covering suicide.

“We did not reveal the person's name and address, or use their pictures. If it was a student suicide, it usually went on page 3,” he explained. “Businesspersons were on page 1. Usually, the more details the better. No directive to sensationalise was given, just that of sticking to the facts.”

A grey area

The guideline asking for suicide to not be given prominence may be problematic in the Indian context, however. Stories involving suicides in the context of farmers or caste oppression cannot be buried in the inside pages of newspapers.

“While the tendency to sensationalise is wrong, the point of featuring the suicide of Dalits or farmers on the first page is to shed light on the larger social scenario driving them to taking their life. In such stories, the identities and circumstances need to be mentioned for a better understanding,” said KS Meenakshisundaram, a professor of journalism and formerly senior deputy editor at The Hindu.

Human rights activist Bezwada Wilson said that suicides across communities, in an unequal society like ours, cannot be generalised. “Each suicide has a unique reason and social factors behind it, and these need to be highlighted to separate it from suicides that stem from individual woes.” He reckoned that while editorial guidelines vary among organisations, common sense dictates that suicides of deprived people be highlighted.

Independent journalist Neha Dixit, who has covered farmer’s suicides, said suicides need to be examined as part of a larger narrative.

“It is important in a country like India with a large number of suicides – of farmers and of women – to talk about the reasons leading to the loss of lives,” she said. “All discussion and debate should happen constructively, to talk about the causes of marginalisation of people taking such drastic measures.”

Given this, it appears that the Press Council’s guideline, based on the WHO’s recommendation about not featuring suicide stories prominently in newspapers, is out of sync with India’s realities.

The way ahead

Experts and media professionals agree that reportage has become more sensitive over the past few years, particularly after the Press Council asked the print media to incorporate the WHO’s guidelines. A cursory look at the nature of reports in the context of the recommendations would suggest that news organisations need to look at suicides from a larger perspective. And in doing so, they would realise that, through irresponsible reporting, they are capable of pushing an at-risk individual over the edge.

Indian media is an upper-caste fortress, suggests report on caste representation

Indian media is an upper-caste fortress, suggests report on caste representation How to report on gender-based violence

How to report on gender-based violence