‘Inhuman and illegal’: The battle over media layoffs in the Supreme Court

Last week, the News Broadcasters Association and the Indian Newspaper Society responded to a PIL challenging layoffs by media companies.

On April 16, three journalists' associations joined hands to file a public interest litigation in the Supreme Court of India. The National Alliance of Journalists, the Delhi Union of Journalists, and the Brihanmumbai Union of Journalists moved the apex court to halt the prevailing layoffs, furloughs and pay cuts in the Indian media after the imposition of the nationwide lockdown to tackle the coronavirus pandemic.

The PIL was filed as a writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, which gives individuals the right to move the Supreme Court if they feel that their rights have been “unduly deprived”.

The tremors of the dreaded “cost-cutting measures” hit Indian newsrooms soon after the lockdown on March 25. By mid-April, English dailies like the Indian Express, the Hindu and Hindustan Times had announced pay cuts; news website the Quint had rolled out furloughs; and there were layoffs at the digital arm of News Nation, a TV news channel. The Times Group handed out pink slips to employees of Times Life and Economic Times, and over a dozen employees at the Marathi daily Sakal Times were sacked.

The trend is global. American websites Buzzfeed, Vox, Quartz and Vice have together furloughed and fired more than 400 employees in the last 30 days. Ninety employees at the London-based The Economist were handed pink slips last week. Condé Nast, the group that publishes magazines like Wired, GQ, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, laid off about 100 staffers and furloughed another 100. Dozens of newspapers in the US have also announced pay cuts and layoffs.

In the Supreme Court, the petitioners were represented by senior counsel Colin Gonsalves. Solicitor General Tushar Mehta appeared on behalf of the Centre.

On April 27, a bench of Justices NV Ramana, Sanjay Kishan Kaul and BR Gavai admitted the petition and notified the Centre, the Indian Newspaper Society, and the News Broadcasters Association, asking them to reply within two weeks.

The News Broadcasters Association filed its counter-affidavit in the Supreme Court on May 11, and the Indian Newspaper Society on May 13. The Centre is yet to submit a reply.

The case against layoffs

The petitioners crutched their case against the “inhuman” and “illegal” layoffs upon two main arguments: that they went against advisories issued by the Centre and state governments to refrain from layoffs and retrenchments during the lockdown period; and they violated existing laws like the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, and the Working Journalists Act, 1955.

“The nature of injury caused to the public is that this is an affront to the rights of journalists and also impedes their ability to perform their duties and provide independent journalism as a pillar of democracy,” the petition said.

The document began with quoting speeches made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in March and April this year, where he spoke about the importance of mediapersons and asked his audience to be compassionate towards “people who work with you in your business or industry” and to not “deprive them of their livelihood”.

It cited a March 24 order by the Ministry of Home Affairs which exempted “print and electronic media” operations during the lockdown to argue that print, electronic and digital media were carrying out essential services.

The petitioners added that a March 20 advisory from the Ministry of Labour and Employment had asked states, union territories and the “All Employers’ Association” to “extend their coordination by not terminating their employees, particularly casual or contractual workers from job or reduce their wages.”

The petition continued: “The termination of employee from the job or reduction in wages in this scenario would further deepen the crisis and will not only weaken the financial condition of the employee but also hamper their morale to combat their fight with this epidemic.”

According to the petition, retrenchment by media outlets went against Sections 25O and 25N of the Industrial Disputes Act. Section 25N states that an industrial establishment must fire a worker only after serving a three-month notice along with written reasons. It should also take prior permission from the government for such a call. Section 25O legally bars an establishment from closing down without the government’s permission.

Section 16A of the Working Journalists Act, the petitioners said, also prohibits a newspaper from retrenching any employee over his wages.

“What media establishments/employers are prohibited from doing by law, they are trying to achieve by subterfuge taking the excuse of the lockdown due to [the] spread of coronavirus,” the petition said.

It further pleaded that the court suspend all firings, furloughs and pay cuts of journalists and non-journalists at media outlets.

‘Survival is at stake’: NBA’s counter-affidavit

In a counter-affidavit filed on May 11, the News Broadcasters Association challenged the fundamental claim that the petition was a writ petition and a PIL in the first place.

It held that the petition concerned personal contractual rights between an employer and its employees, and therefore was not maintainable under Article 32, as proscribed in judgements of Ramesh Sanka v. Union of India & Ors (2019) and KK Saksena v. International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (2015).

It added that the petition did not have the essential requirements of a PIL: “Nowhere in the entire petition has it been brought out that the issue raised and the relief prayed is in the interest of [the] public. Rather, the petition is in self-interest of the petitioners and clearly the employment and economic interests of the members of the petitioners are involved.”

The organisation argued that the Industrial Disputes Act is not applicable to news broadcasters, especially Section 25N, which purportedly only covers factories, mines and plantations. Similarly, it claimed that the Working Journalists Act too does not cover electronic media, which the News Broadcasters Association claims to represent.

It added that the advisory by the Ministry of Labour and Employment cited by the petitioners “is merely an advisory and hence not mandatory in nature”.

The most interesting revelation in the counter-affidavit is the association’s response to the prime minister’s speech and the appeal by the petitioners that journalists are engaged in an “essential service” during the lockdown.

Pointing out that the pandemic has put it in a dire financial situation, it argued: “Since businesses are barely operational and consumer demand is at an all-time low, Advertisers are not interested in advertising during this pandemic period and advertisement volumes and revenues have drastically reduced since the advent of Covid-19.” It added that the News Broadcasters Association has “suffered huge financial losses and their very survival is at stake”.

It said: “The exemption from lockdown is no ground for seeking prohibitions on the right of the employer to take the necessary action within the framework of the applicable employment laws.”

‘Advisories are vague, arbitrary, illegal, unconstitutional’: INS’s counter-affidavit

In its counter-affidavit filed on May 13, the Indian Newspaper Society argued that the respective advisories by the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Labour and Employment were “vague, arbitrary, illegal, unconstitutional and violative of Article 14 of the Constitution of India”.

The advisory by the labour ministry, it noted, did not “differentiate between the workers who report to work and the workers who refuse to work,” and therefore goes against the principle of “equal work, equal pay”. It added that the advisories were excessively invasive, and that the petitioner’s prayer could shut newspaper outlets, who have been “hit very hard by the outbreak with advertisement revenues taking a hit and circulation revenues too going down”.

The counter-affidavit said that government advisories can be treated only as a “moral or humanitarian obligation”, adding: “It is a settled principle of law that a moral obligation cannot be converted into a legal obligation.”

Like the News Broadcasters Association, the Indian Newspaper Society also highlighted the supposed plight of the print media, claiming that not just employees, but employers too are in trouble.

The counter-affidavit claimed: “Journalism forms the fourth pillar of democracy, and letting these establishments run into the ground could lead to horrible ramifications. The lack of business due to the lockdown, the impact on business due to Covid-19 and the continued payment of salaries and wages could potentially drive the private establishments into insolvency, unless suitable economic policies and financial measures are brought in by the government to safeguard the industry and economy.”

The affidavit said that advertising revenue is the “lifeblood” of a newspaper. Since the lockdown, it claimed, there has been a decrease of approximately 80-85 percent in government advertisements and a drop of approximately 90 percent in “other advertising”.

“In a situation like this, mandating these establishments to keep on paying the same amount of salaries, while the revenues are dropping, would effectively mean that all of these establishments will have to close down,” the Indian Newspaper Society continued.

In a broadside to the government, the body pointed out that the government should pay newspapers the money it owed them for advertisements. It claimed that the Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity owes Rs 800-900 crore to print media outlets.

With respect to the Industrial Disputes Act, the organisation retorted that Section 25M of the Act recognises that employers are permitted to lay off their employees as a result of a “natural calamity”. It added that the petitioners had misread the Working Journalists Act, and that the affected parties should approach the “appropriate forum” provided under the act. This, it said, had been laid out by the Supreme Court in Premier Automobiles Ltd v. Kamlekar Shantaram Wadke of Bombay and Ors (1976).

It added that a writ remedy under Article 32 can be invoked only in the most extraordinary circumstances.

***

The media industry is in crisis. Journalists, more than ever, need your support. Support independent media and pay to keep news free. Because when the advertiser pays, the advertiser is served, but if the public pays, the public is served. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

To learn more about the economics of the news ecosystem, sign up for Stop Press, a weekly newsletter.

For newspapers battered by the economic slowdown, Covid-19 is the final blow

For newspapers battered by the economic slowdown, Covid-19 is the final blow

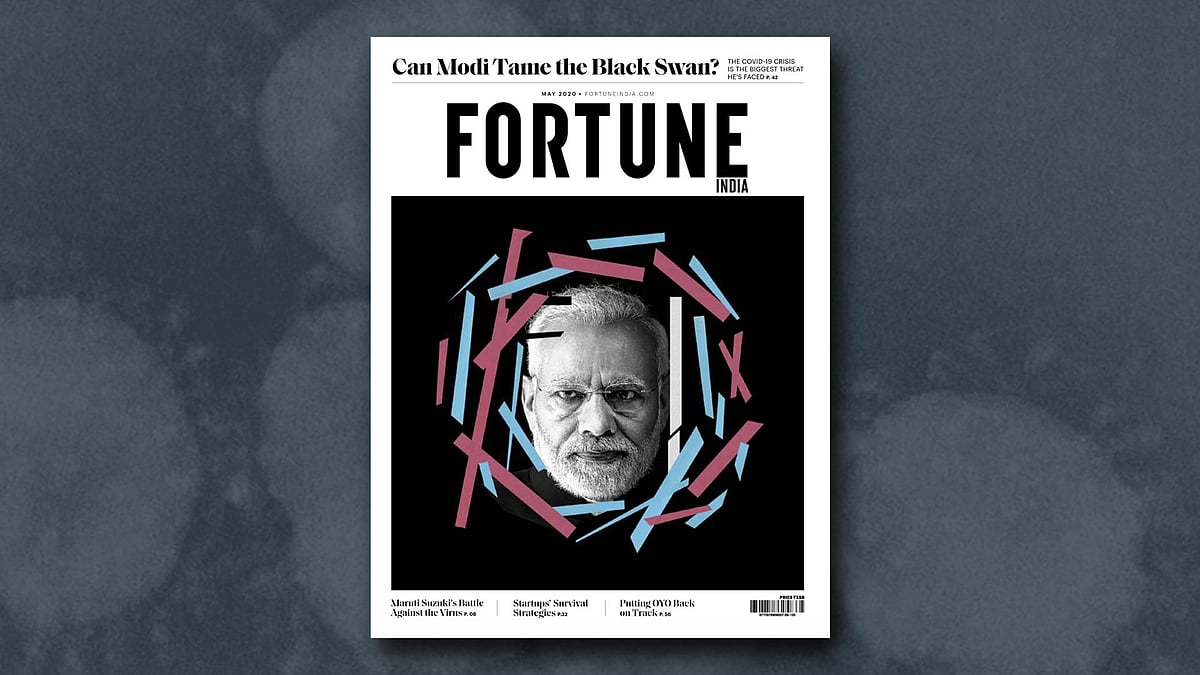

'They plan to sell the magazine': Why Fortune India staffers are refusing to take 'voluntary' furlough

'They plan to sell the magazine': Why Fortune India staffers are refusing to take 'voluntary' furlough