Mylapore Times: In times of Covid, this community newspaper holds lessons for Big Media

The newspaper has been a staple in south-central Chennai since the 1990s. With the pandemic, it adapted to turn every Covid question from its readers into a story.

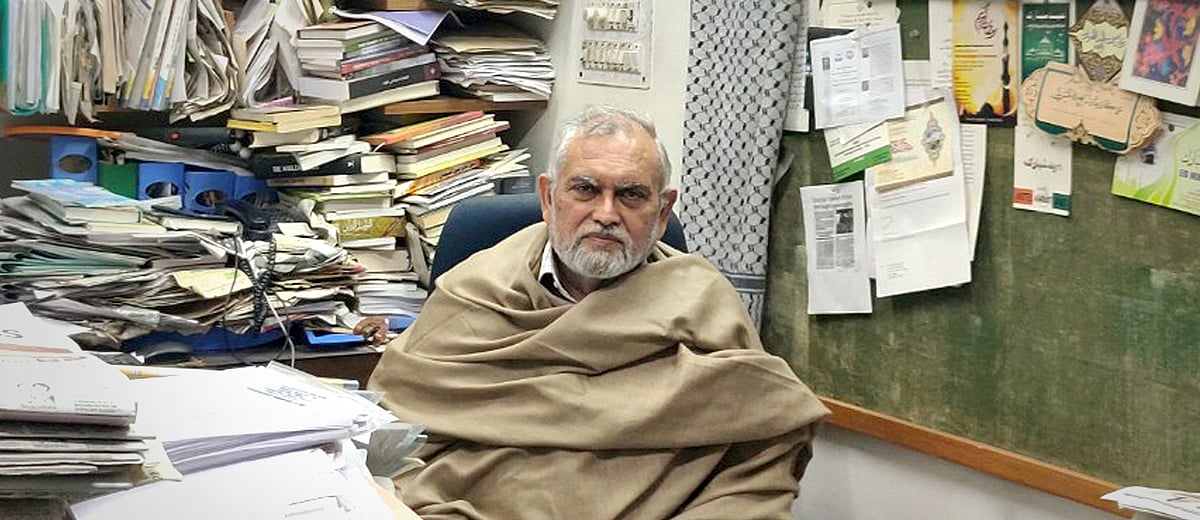

Vincent D’Souza, 60, the owner-editor of Mylapore Times, has the beard and belly of a middle-aged St Nick, the energy of a Duracell bunny, the mind of a bean-counting businessman, and the ticker of a hustling city reporter. In times of Covid-19, he fancies himself as the agony aunt of Mylapore’s residents.

And there is plenty of agony around: the “R Naught” of agony and anxiety in not just Chennai’s Mylapore, but all of the Covid-battered city today, is far higher than that of coronavirus.

The readers of Mylapore Times expect D’Souza to have the answers for questions the civic authorities, police, or assorted arms of the government don’t. A man living in the US wants to know how his 70-year-old father living alone in an apartment in a designated containment zone in the neighbourhood can get some urgent plumbing done. The residents’ welfare association won’t let workers in, and the water supply is fast running out.

A young woman in her twenties, recently laid off by a BPO firm, is desperate for a job. Since the Chennai Corporation is the only organisation hiring, she calls D’Souza up to ask after the procedure to become a Covid-19 volunteer. The volunteers, paid Rs 15,000 a month, are deployed to conduct door-to-door health checks. Another US resident is stricken by panic because his 76-year-old mother back home is experiencing dizzy spells. It’s impossible to get a doctor’s appointment. Can D’Souza help? He posts the SOS message on the publication’s Facebook page and soon enough, a doctor at a large Chennai hospital chain is ready to consult via video call.

Mylapore, a four sq km neighbourhood in south-central Chennai, is arguably the oldest extant non-agrarian settlement in the city. Tiruvalluvar, preeminent among ancient Tamil poets, is believed to have lived here some 3,000 years ago. It is home to the 7th century Kapaleeshwara temple and the 16th century Santhome basilica built by the Portuguese. Its real estate is among the most expensive in Chennai and some of Chennai’s most affluent live here; yet in spirit, it remains firmly middle-class.

Like many such vibrant urban settlements with a hoary past, Mylapore’s residents too lay a credible claim about it not merely being a prized pin code, but a state of mind.

In the early 1990s when D’Souza was toying with the idea of starting a community paper in Chennai, he was convinced that if it didn’t work in Mylapore, it wouldn't work anywhere else.

“The place had a certain cohesiveness and community pride that you couldn’t find anywhere else in Chennai at the time,” says D’Souza. With support from the Research Institute for Newspaper Development, an organisation promoted by a consortium of large newspapers to develop better publishing standards, D’Souza quit his job at the Week magazine and set up Mylapore Times in 1994. A small grant from a German fund helped him buy a couple of computers for the new paper.

Mylapore Times started off as an eight-page weekly tabloid published on Saturdays. The response was such that the newspaper soon became a 16-pager with colour printing. Until March 23, 2020, when the printer refused to roll it out with the Covid-19 crisis worsening, the paper had a weekly print run of 30,000.

The success of Mylapore Times forced even the big newspaper groups to try their hand at neighbourhood-specific supplements. It also spawned many copycat community newspapers in Mylapore and elsewhere in Chennai, but not many have survived. Some were fly-by-night operations. They simply could not match Mylapore Times’ organic connect with the community and its professional journalism driven by D’Souza.

A disclosure and bit of a personal backstory: I started my journalism career in 1998 at a new community newspaper that D’Souza had started, aimed at the fast developing neighbourhoods in western Chennai. The weekly editorial meetings with D’Souza were dreaded affairs. They were interminably long and involved several rockets fired up the backside. A taste for masochism developed in D’Souza’s newsroom is perhaps a reason why I remain a journalist.

At one such meeting, there occurred a post mortem of a big story I’d written that week on the murder of a housewife in the neigbourhood. Ten minutes into a monologue about how terrible the piece was, D’Souza threw on the desk the latest issue of Time magazine, with John F Kennedy Jr’s death in an air crash on its cover.

“Why the hell couldn’t our coverage be like this,” he barked. At the time, I thought this was either world-class mickey-taking, or the man needed psychiatric help.

A crisis needs more reportage

The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated the meltdown of big media business models. While the stories of large-scale layoffs, shabby treatment of journalists by media owners, and shrinking newsrooms may only find a place in publications such as Newslaundry, they’ve generated plenty of debate on social media about societal and democratic consequences.

But what about small, independent hyperlocal media organisations such as Mylapore Times? They too speak truth to power, perhaps more often and more meaningfully, and offer as much service to the cause of democracy, if not more, than the mainstream media. They have sustainable business models without the need for philanthropic grants or venture capital funding. The response of a tiny community newspaper like Mylapore Times in times of Covid-19, and its approach to business in general, holds many lessons.

Given its readership and purpose, it didn’t make sense for Mylapore Times to spend money on online operations. It had a functioning website, but the paper got all the attention. Forced to stop printing, the first thing D’Souza did was to ramp up reportage and use the website and social media like never before.

“A crisis like Covid-19 is when we have to stand up and be counted. This is when you know what your paper is worth,” he says. “We decided to think and act like a daily newspaper.”

Used to the rhythm of a weekly production cycle, the three-member team of reporters (that includes D’Souza) and two photographers (the ad sales executive now doubles up as a cameraman) file a much higher number of stories now, and as they happen. There’s plenty to report, even if it is an unending stream of bad news.

Mylapore Times’ pages these days are full of obituaries of Covid-19 victims. D’Souza records a two to three minute audio bulletin on his phone twice a day with updates on new containment measures, testing labs, and even obits of well-known citizens in the community.

“People now have a diverse range of doubts,” D’Souza explains. “Can I get an auto outside the fever clinic? When will the traffic police release my vehicle which was seized during the lockdown? Can I get a caregiver for my 80-year-old parents who live alone? Are the markets open today, is it safe to step out and buy vegetables? The messaging from the government is overall so poor that no such questions are too small.”

But for Mylapore Times, every question is a story. “This is a role big newspapers refuse to play. Our newspapers keep telling us that this pandemic is monumental and has changed everything but somehow, their pages and the approach to journalism remain the same. They’ll tell you about how bad the World Health Organisation’s response to the pandemic is, but not where to go if you have Covid-19.”

There hasn’t been any income for nearly three months but Mylapore Times has managed to retain its nine-member staff on full salary, thanks to the prudence of the past. There may be enough in the bank to last a few more months and not pare down its monthly salary bill of Rs 2 lakh.

Community immunity

A typical 16-page issue of Mylapore Times would have stories on civic issues (broken canals, potholed streets, encroached pavements, unresponsive officials), local temple festivals, uplifting human interest stories such as a group of seniors training for marathons, reports of alumni meetings of 100-year-old schools, the opening of a new Chettinad takeaway, the arrival of maavadus (baby mangoes used for pickling) in the market, admission updates at local schools, or a neighbourhood girl making it to the state or national football team.

The stories are short and crisply edited. Almost every story ends with the address and phone number of the person or service written about.

There’s no space to spare for grandiloquent editorials. Instead, there’s a sunny 400-word column by D’Souza usually on something related to Mylapore or Chennai. On Saturdays, nearly 70 percent of the print run of 30,000 is door delivered and the rest stocked at prominent drugstores and department stores. The paper disappears in less than an hour.

“TV and the big newspapers can tell us about what’s happening on the border with China or the Black Lives Matter protests halfway across the world, but how do I get to know what’s happening in my immediate surroundings? That is equally important to me. That’s why Mylapore Times has become a habit and a part of community life,” says CS Bhaskar, 61, a car battery seller and a lifelong resident of Mylapore.

“You can’t underestimate its importance especially for women and senior citizens, whose engagement and dependence on the community around them is very high,” Bhaskar adds. “In fact, I often tell Vincent that he should print at least 50,000 copies of the paper.”

This sense of kinship with the community has been Mylapore Times’ insurance against the big consumption shift to digital media. “Social media has only added to the relevance of neighborhood journalism. In fact, I consistently increased my circulation and advertising rates in the last 10 years,” D’Souza says. “Information on people, local events, utilities and space for grievances remain relevant in this age. Not many big media organisations can claim to know its readers as well as we do.”

Keeping the paper free eliminates the hassle of newsstand sales, agent commissions, and tracking circulation receivables. The revenue comes from advertising and classifieds that are hugely popular. A classified ad can cost as little as Rs 300, while an advertising column centimetre is Rs 220. Though not entirely comparable but to put it in perspective, the ad rates at the Chennai edition of the New Indian Express, with roughly similar circulation numbers, could be about 25 times higher.

The advertising in Mylapore Times is almost entirely from local businesses — neighbourhood boutiques, catering services, tuition centres, small real estate developers. There’s no credit; ads are booked only upon payment. D’Souza refuses to deal with ad agencies who might get him ads from much bigger brands. With the tight ship he runs, he can’t afford the 60- or even 90-day credit period it involves (and a lot of chasing up thereafter too).

By any measure, media enterprises are hard to start and sustain. If media entrepreneurs don’t have big, hairy, ambitious goals (or BHAG, in investor-speak) built into their proposals, a seed fund would not even give them a look in. Mylapore Times may not have BHAG, but its balance sheet is firmly in the black. Before it stopped printing, the paper had an average weekly net profit of Rs 1 lakh.

D’Souza has evaded the media business death traps of irrational quests for size and influence, unwieldy operations, and political or ideological partisanship. His ambition is not to expand into a chain of neighbourhood newspapers or a maze of online properties and apps, but to find ways to make Mylapore Times more useful to the community.

If anything, such commonsense and humility seems irrational in the media market.

***

The media industry is in crisis. Journalists, more than ever, need your support. You can support independent media by paying to keep news free. Because when the public pays, the public is served and when the advertiser pays, the advertiser is served. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

The curious case of ‘The Milli Gazette’

The curious case of ‘The Milli Gazette’