Ithu oru pon maalai pozhuthu: How I learned about my mother through the music of SPB

For a 21-year-old living far away from home in the 1970s, SPB was the vehicle that gave her life.

I don’t know anything at all about the neuroscience or psychology in relation to the power that the memories of sound exert upon us. I can only tell you that few things fill me with more happiness and joy than Tamil film music of the late 1970s and early 1980s. It is perhaps almost entirely down to the fact that it made my mother happy.

In 1976 at the age of 21, her wagon was hitched by horoscope to a man whose work life had forced her into exile, far away from her beloved Madras, to the small towns of central India. A combination of homesickness, the drudgery of domesticity in distant lands that offered no familiar distractions, the derision of being labelled a Madarassi and the exclusion from immediate social life, and household finances always in a state of permanent distress if not disarray, shaped her disdain for life in general and All India Radio in particular — the state broadcaster and my father’s employer.

But some mood-altering magic occurred every evening at around sundown. The elaborate evening ritual of combing her long, coconut-oiled hair, that made north Indian neighbours envious, was accompanied by the crackling voice of the radio presenter introducing the Chennai vaanoli nilayam’s Vividh Bharati service.

Her eyes lit up. She didn’t hum; she sang along, out loud.

At age four, I couldn’t quite figure out why the announcer’s words — “Isai Ilaiyaraja, paadal SP Balasubrahmanyam, S Janaki” (Music Ilaiyaraja, voice by SPB and S Janaki) — had such an effect on her. Perhaps it took her mind off the banality of grinding idli batter or pounding roasted coffee beans to satisfy a husband who expected her to recreate Kumbakonam for tiffin in Chhattisgarh. I felt the music of this troika formed a kind of key to unlock a small window of happiness for her.

Ever since, the combination of these three names has had a special place in my life. For instance, the superhit song Ithu oru pon maalai pozhuthu in SPB’s voice from the 1981 dud Bharathiraja-directed film Nizhalgal was played so frequently on the radio during those times that I can imagine it being 5.30 pm somewhere whenever I listen to it.

The other high point of my mother’s life was the preparation for which sucked in most of her energy and the family’s savings. It was the annual summer trip back home to Madras, from Itarsi — the nearest railhead no matter where we lived — on the Grand Trunk Express’s 40-hour, “superfast”, 2,100-km snaking journey from Delhi, the heart of India, to Madras, on the country’s shin.

Upon arrival at Madras Central, my mother usually headed to her mother’s place in Perambur, then in the industrial northern periphery of the city. Perambur provided easy access to the cinema halls she was familiar with. Ega and Abirami in Purasawalkam were pretty much her home territory. A 30-minute bus ride took her to Shanti and Devi and many other theatres around Mount Road. She could watch two films a day, sometimes even three, if things went to plan.

An exhaustive mental-list of must-watch movies would have already been made in Raipur or Jabalpur, based on the songs of the films she’d fallen in love with, or influenced by the reviews in Ananda Vikatan or Kumudam.

Of the 200-odd Tamil films that released every year, my mother managed to watch at least 30 in those few summer weeks. She would come back humming SPB’s voice lent to a romantic Kamal Haasan, “Mike” Mohan, a dashing Rajinikanth, or nobodies like Rehman (the actor, not music director), Suresh or Sudhakar. She was so much in thrall of the song Enna sattham inda neram that she saw the film Punnagai Mannan god knows how many times.

I began to suspect SPB was more important to her than my father.

SPB’s photographs in Tamil magazines were reassuring. This overweight man was no match for my father with a better moustache, whom I had heard my aunt describe as a mixture of Guru Dutt and Kishore Kumar. But not entirely convinced, I demanded to be taken to a show of Punnagai Mannan. My mother fobbed me off saying it was “for adults only”.

I waited.

In any case, I was in a sort of music coma until I turned 18. In the meantime, super-duper musicals had come and gone by the time we relocated to Chennai, bag and baggage, such as Karakattakaran, Vetri Vizha, Thalapathi and Gunaa in Ilaiyaraaja’s music, and Roja, May Maadham and Gentleman (in Rahman’s music).

I discovered the transcendental power of music when forced to report on Carnatic classical music and dance sometime around 1999. My discovery of Ilaiyaraaja, and the contribution of SPB to his stellar output, was in some ways a result of reverse osmosis. Ilaiyaraaja had been conducting unprecedented experiments in building a bridge between “high” and “popular” forms of music. SPB had not merely been the voice of superstars Rajinikanth and Kamal Haasan for all of their “introduction” songs, but an inseparable part, along with S Janaki and KJ Yesudas, of such experiments in creating a new musical paradigm for cinema.

SPB’s untrained voice was the veritable vehicle for Ilaiyaraaja and many other music directors’ attempts at innovation. He was an essential part of the gilded age of south Indian cinema of the 1980s when it was difficult to lose money if Ilaiyaraaja composed the music with SPB singing some of them.

Sripathi Panditaradhyula Balasubrahmanyam was born to a family of amateur singers in the bhajana sampradaya, or traditional Brahmins who specialised in singing Telugu and Sanskrit songs during temple festivals in Andhra Pradesh. His first big break arrived in 1969 in the form of Aayiram Nilave Vaa in the film Adimai Penn featuring MG Ramachandran and Jayalalithaa.

Like most fresh singers, by SPB’s own admission, he tried to imitate the singing stars of his time, TM Soundarrajan and Mohammad Rafi. Just as Rafi had tried to copy Talat Mehmood. But big-time national recognition came unexpectedly with his Carnatic-based song Sankara nada sarirapara for the Telugu film Shankarabharanam, directed by relative K Vishwanath and music composed by a classical music-oriented relic of the past, KV Mahadevan. If you ask me, SPB’s singing in the film and Mahadevan’s music are an affront to Carnatic music. I cannot find it in me to forgive the mangling of Broche Va, a great Carnatic classical composition, in this filmy version by SPB and Vani Jayaram. But we shall let that pass.

Beyond such aberrations, he was faultless. In music and personal conduct.

When I first fell in love, the only song I wanted to sing to my subject of affection was Idhazhil kadhai ezhudum neram from the K Balachandar film Unnal Mudiyum Thambi, even if she couldn’t understand the lyrics. When that endeavour bombed, I moved on. I found someone who would be a bit more impressed by my imitations of SPB in Tamil. During a rainy October evening in 2004, blinded once again by love, when we were, to use one of Private Eye magazine’s famous euphemisms, “tired and emotional”, I summoned the SPB song Andhi Mazhai Pozhigiradhu to good effect.

I’ll leave you with one last SPB song called Vandhaal Mahalakshmiye in the superlative Carnatic raga Kalyani, which sustains the bond of love that’s turned into the covenant of marriage. It can help you too, whether you are a millennial or GenZ.

Thank SPB, and grieve not a life that was lived to the full which gave us more than 40,000 songs for all moods.

***

The media must be free and fair, uninfluenced by corporate or state interests. That's why you, the public, need to pay to keep news free. Support independent media by subscribing to Newslaundry today.

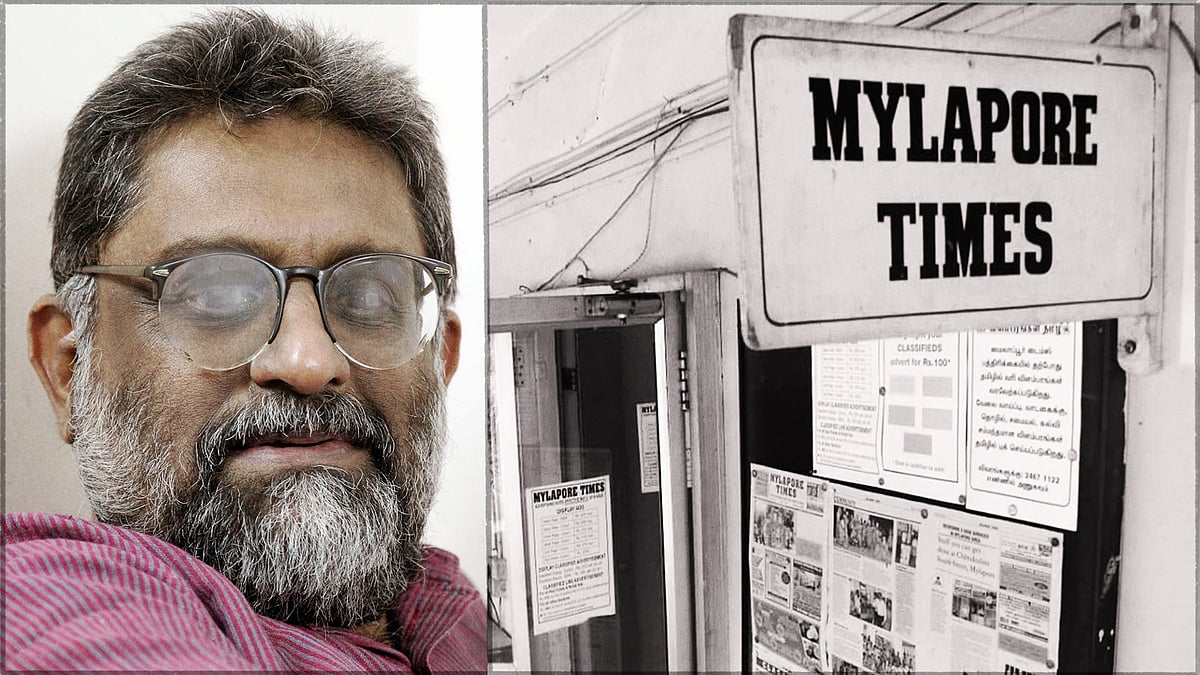

Mylapore Times: In times of Covid, this community newspaper holds lessons for Big Media

Mylapore Times: In times of Covid, this community newspaper holds lessons for Big Media

TN Seshan: The crusader and newsmaker India needed in the 1990s

TN Seshan: The crusader and newsmaker India needed in the 1990s