Comparing Modi and Vajpayee eras of coalition politics is misplaced. Here’s why

There’s a tendency to fondly remember the ‘sensitive handling’ of allies by previous NDA governments, but this ignores historical context.

Following the examples of the Telugu Desam Party and the Shiv Sena in recent years, the Shiromani Akali Dal’s decision last week to walk out of the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance over the farm legislations has engaged political commentators.

One line of evaluating the decisions of estranged allies has been by seeing these moves as a result of the lack of coalition management and consensus-building in the current BJP leadership. This particular view tends to juxtapose the current approach with what it recalls as the more accommodative and sensitive handling of allies by former NDA governments, comprising a total of six years, at the centre under Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

However, such a prism is often blurred with flawed historical context and blinded by nostalgic exaggerations. In the process, such comparisons reveal the lack of historical understanding of the imperatives of alliance politics in the NDA governments of two different periods. More significantly, they fail to grasp the difference in the very nature and scale of the electoral mandates of the two governments and its implications for terms of engagement in the alliance.

To begin with, the severely fractured poll mandates that paved the way for the coalition era in Indian politics in the late 1980s, and more definitely in the ‘90s, reopened some of the BJP’s old wounds. The party had anxious memories of its political ostracisation when it came to the question of partnering with other political parties. The leaders of the Jan Sangh, the party to which the BJP owes its origin, had voiced their disappointment with this attitude of other parties of a potential anti-Congress front. In 1967, in the Jan Sangh’s party plenary meeting at Calicut, Deendayal Upadhyay talked about political untouchability practised against the party. However, he also alluded to the possibility of political permutations and poll numbers making some parties agree to partner with the Jan Sangh.

In his work, The Saffron Tide: The Rise of the BJP, Kingshuk Nag noted that while referring to such a scenario emerging, Upadhyay gave the example of the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal governments that were formed in many states in 1967 after the general election. In a rare coming together of the Right and Left streams of Indian politics, the Communist Party of India allied itself with the Jan Sangh in states like Bihar and Punjab to form governments.

While a strong imperative of anti-Congressism again made it possible for Jan Sangh leaders to find a place in the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party government in 1977, the spell of isolation came back to haunt them over the question of the dual membership of the new government and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Once they decided to walk out of the government and revive and rename their party in 1980, the BJP braced itself to go it alone until it had the electoral numbers to become a decisive voice. It only lent outside support to the anti-Congress front in 1989, the short-lived VP Singh government.

However, in the first half of the 1990s, the party’s strategic thinking took note of the further diffusion of political support centres in the country in the form of regional parties, which had forced even the Congress to cling to a precariously slender majority at the centre, being either ousted from many state governments or fiercely challenged. The BJP’s projection of Vajpayee as a prime ministerial face was as much shaped by LK Advani’s decision to wait out the period for clearing his name as it was by the higher probability of the former’s acceptance by potential alliance partners at the centre. This clearly wasn’t enough, as was proved by the party’s failure to get allies for its short-lived 13-day government following the 1996 Lok Sabha poll.

Two years later, it was eventually the higher probability of stitching together more poll numbers, as Upadhayay had predicted, that enabled the BJP to form a pre-poll alliance with a number of parties. Far from having an all-India footprint, the BJP hoped the new alliance would help it make a foray into different regions and gather resources and parties around the glue of anti- Congressism. The newly-formed combine, named the National Democratic Alliance, did win a simple majority under Vajpayee.

However, bereft of a majority of its own, the BJP was forced to rely heavily on its allies, somehow coping with all their pulls and pressures. The first NDA experiment at the centre was cut short by its ally, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, withdrawing its support and pulling down the government by merely one vote in 1999. Clearly, for all all the talk of a Vajpayee model of consensus-building, the basic objective of running a full-term government was subjected to the vagaries of political behaviour.

When voted back to power in 1999, the more cautious approach of the Vajpayee-led NDA towards its allies was obvious. Its imprint of survival mode at the time was clear. Along with this, political scientists like Suhas Palshikar have talked about two ways in which the NDA stood in good stead for the BJP of that period. He wrote:

“It ensured an electoral front that could help the BJP become a critical player nationally and form the government in Delhi. Secondly, it allowed the BJP to obtain a foothold in states where it did not have a presence. If one looks at the growth of the BJP in Karnataka, Maharashtra or Bihar, between 1996 and 2004, this latter purpose was admirably served at the cost of state parties. Therefore, it was for the state parties to take a call on how long to go with the BJP.”

However, for the core voting groups of the BJP, talks of a consensual approach and coalition duty were euphemisms for compromise. These voting groups wanted the imprint of Vajpayee’s party on the government, and perceived that the NDA was either too cautious or tied down by coalition compulsions to be identified as the party that the core supporters had endorsed. So when the party president at the time, Venkaiah Naidu, said “BJP ka jhanda, NDA ka agenda (BJP’s flag, NDA’s agenda),” the core voter wished the slogan could be reversed to say, “NDA ka jhanda, BJP ka agenda.”

Almost a decade and a half later, the landslide victory of the Narendra Modi-led BJP in the 2014 Lok Sabha poll, and even more emphatic win in the 2019 poll, gave the party the chance to rewrite that slogan because its own numerical strength makes all its allies dispensable in the short term. After almost three decades, the single party majority is a historical moment which can’t be evaluated with the yardstick of the intervening phase of coalition politics. We can’t know how the celebrated consensual leaders would have treated allies once the latter weren’t needed for the very survival of their government.

However, we can’t lose sight of one important aspect. For three very important reasons — and despite the perceived domineering political style of the Modi-Shah duo — the top BJP leadership today realises that for three important reasons, the BJP cannot quit clinging to its allies.

First, it still needs regional allies to spread and consolidate its footprint in different corners of the country, as Palishikar had remarked. The association of the regional outposts of the BJP with its entrenched regional allies remains relevant for it. Second, the support of its allies in getting legislation passed in the Parliament, particularly given its uncomfortable position in the Rajya Sabha, continues to be significant. Third, the swing in electoral fortunes must always be considered in crafting party strategy, and keeping allies intact is still important for this objective.

Perhaps it’s the realisation of the last factor that was evident in the run-up to the last Lok Sabha poll, especially as the BJP had been facing the possibility of a tough challenge at the time. The BJP leadership showed flexibility in accommodating alliance partners in seat allocation. In Bihar, for instance, out of 40 seats in the state, it settled for five seats less than it won in 2014, deciding on an equal share of 17 seats each with the Janata Dal (United), and leaving six for the Lok Janshakti Party. In less challenging times, the BJP’s current strategy with its allies, as journalist Arun Sinha noted in his book The Battle for Bihar, is to let the allies bake in their own heat till they come to the table.

The approach of the current BJP leadership to its allies is likely to seek the logic of its own time and, to put it more expediently, the rationale of its own numbers. However, it’s aware of the important place that allies continue to occupy in its scheme for all-India power and also as a bulwark against adverse future political developments.

However, seeking parallels with how the coalitions worked in NDA governments at the turn of the century is an exercise in political anachronism.

***

The media industry is in crisis. Journalists, more than ever, need your support. You can support independent media by paying to keep news free. Because when the public pays, the public is served and when the advertiser pays, the advertiser is served. Subscribe to Newslaundry today.

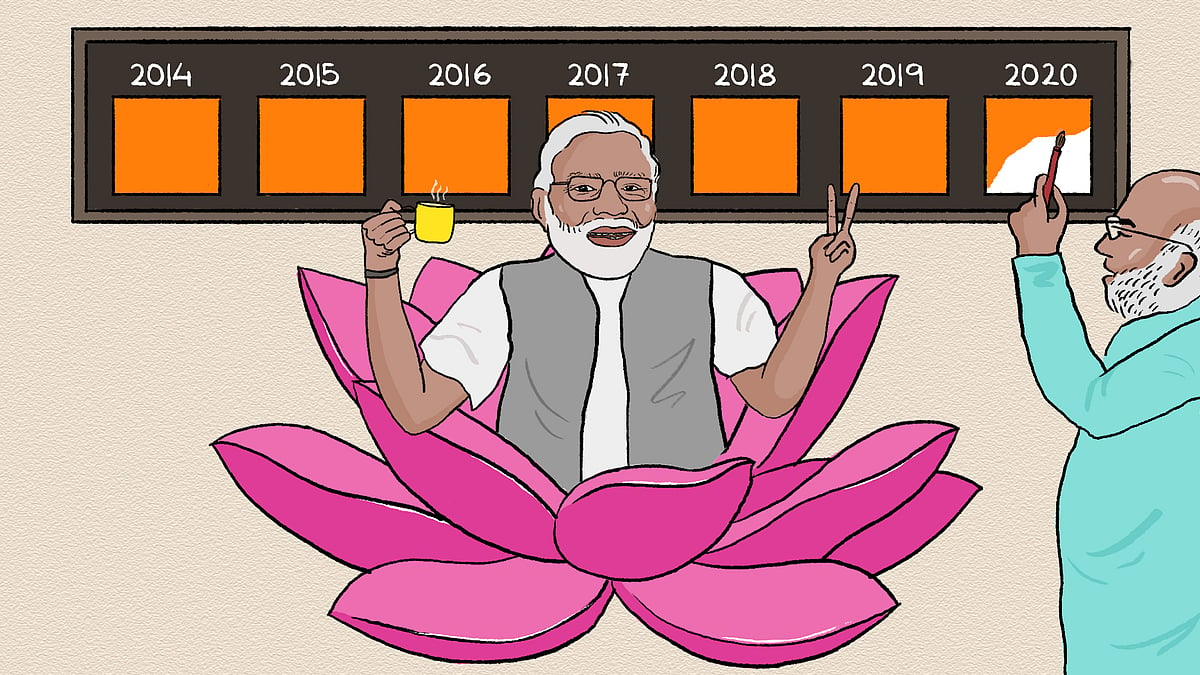

6 years, 2 months, 4 days: Modi’s term marks the longest uninterrupted non-Congress government at the centre

6 years, 2 months, 4 days: Modi’s term marks the longest uninterrupted non-Congress government at the centre