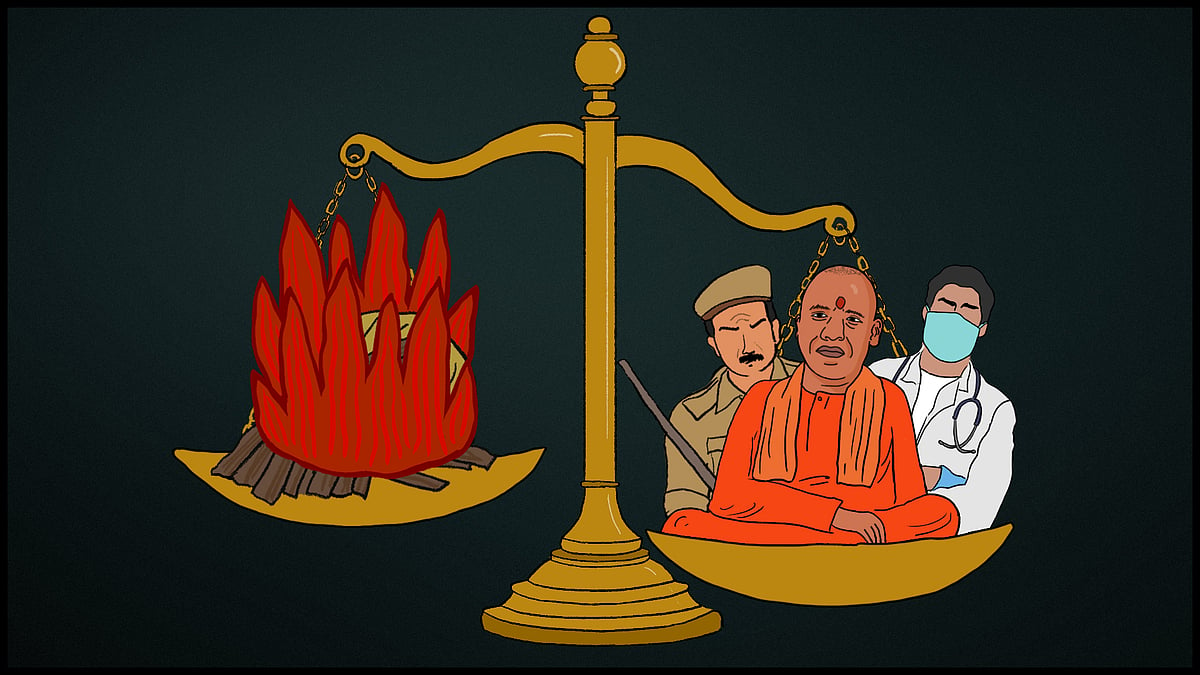

Condemning the Hathras horror isn’t enough. We need to talk about caste and gender in our institutions

If the police and the media are dominated by upper caste men, horrendous levels of injustice will continue.

Deep-rooted misogyny and casteism, in society as well as in the police, have both been on display in the Hathras rape case. Some special investigation teams will be set up, some show of action will take place, and there will be some baying for the blood of the perpetrators.

But this scene is all too familiar. Women’s rights activists are fatigued with writing press statements and articles, and organising protests and candlelight marches.

The blatant discrimination in the media’s reporting of rape cannot be ignored either. The Nirbhaya case, the Hyderabad case, and the Shakti Mills case got far more attention than the Dalit rape cases that take place on a daily basis. The victims in the former were upper caste and middle class women, to whose pain the media and middle classes could relate. The rape of Dalit women showcases the compounded discrimination faced by Dalit communities, especially Dalit women.

India is deeply uncomfortable with talking about casteism. Young professionals claim there is no caste in India. There’s anger when India’s casteism is brought up in the United Nations. There’s a widespread inability to understand the particular realities of Dalit lives, leading to blatant protests against reservations during admission season. All this points to our deep discomfort and denial of the stark caste-based and intersectional discrimination in India.

A lot needs to change. We, as a society, need to change.

Therefore, condemning the brutal rape of a Dalit woman and the subsequent police action of clandestinely, and forcibly, burning her body is not enough. Condemning it is the least we can do. More importantly, we need to underline, again and again, the root causes and what needs to change. We need to acknowledge as a society that we have failed the most marginalised among us, most notably the Dalit communities.

Let us examine two institutions that need to function optimally both for the efficient delivery of justice as well as the accountability of democratic structures.

Take the composition of the police force, which lacks both diversity and gender equality, as pointed out in the 2019 report Status of Policing in India. Across states, there are vacancies in reserved positions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and women; we are still too far from discussing recruitment for Dalits and Adivasis in the general category. Uttar Pradesh fares the worst, with only 40 percent of its reserved positions for the police filled. Women’s representation in the police across India is a mere four percent. Women and SCs in the police are less likely to be officers than general police personnel. The percentage of women officers across states ranges from 2.6 percent in Himachal Pradesh to 27 percent in Madhya Pradesh. In Uttar Pradesh, it is 6.2 percent. Officers among the SCs range from 6.7 percent in Uttarakhand, to 24 percent in Maharashtra, to just 8.1 percent in Uttar Pradesh.

Given the poor social inclusion in the police, it is not surprising that the force harbours biased attitudes. According to the report, one in five police personnel strongly believes that complaints under the SC & ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act are false and motivated. This is the belief held by 83 percent of Uttar Pradesh’s police force; 41 percent believe this is “very much” the case. There is also wide-spread caste bias practiced within the police in the country.

Nearly one in five police personnel believes that complaints of gender-based violence are false and motivated to a large extent. Hostility towards women is also rampant in the police force. It is this lack of social inclusion that leads to delays in investigations into crimes against women and Dalits. It is now known that policing smaller crimes and ensuring certainty of punishment acts as a deterrent, rather than focusing on severity of punishment. Neglecting initial transgressions creates impunity for perpetrators to commit far more heinous crimes.

On the other hand, a majority of undertrials in petty and more serious crimes are from the most marginalised communities. They languish in jails without being convicted for terms longer than what they’d be charged with if they were convicted.

The second institution we’ll look at is the media. A 2019 report by Oxfam India and Newslaundry shows that media houses fare rather poorly in social inclusion. Only about five percent of articles in English and 10 percent in Hindi are written by Dalit reporters, while 72 percent of bylined articles are by upper caste reporters. Just one percent of cover stories in 12 magazines surveyed were about Dalit issues.

There is not a single Dalit person in a leadership position at the surveyed newspapers and media houses. Three out of four anchors in TV news channels are upper caste, and the majority of panellists in 70 percent of TV news debates are upper caste too.

Similar findings were brought out in the UN Women and Newslaundry report Gender Inequality in Indian Media. Of the Hindi and English newspapers, TV news channels, magazines and digital outlets surveyed, the percentage of women in leadership positions are five, 13.6, 21 and 26 percent, respectively. This needs to urgently change if the media is to become an effective watchdog for crimes against Dalit communities and, particularly, Dalit women.

To restore trust in the police and the law enforcement mechanism, swift action needs to be taken to bring rapists and murderers to book, as also the police who colluded to destroy evidence. However, actions taken must go well beyond investigations of the crime to address the structural issues that continue to perpetuate horrendous levels of injustice.

***

The media must be free and fair, uninfluenced by corporate or state interests. That's why you, the public, need to pay to keep news free. Support independent media by subscribing to Newslaundry today.

Hathras girl wasn’t raped, UP police say. Wasn’t she?

Hathras girl wasn’t raped, UP police say. Wasn’t she? ‘Help us get justice, please’: Dalit girl assaulted in UP’s Hathras succumbs

‘Help us get justice, please’: Dalit girl assaulted in UP’s Hathras succumbs