New digital media rules ‘go far beyond what’s permissible in a democracy’: Plea in Delhi HC

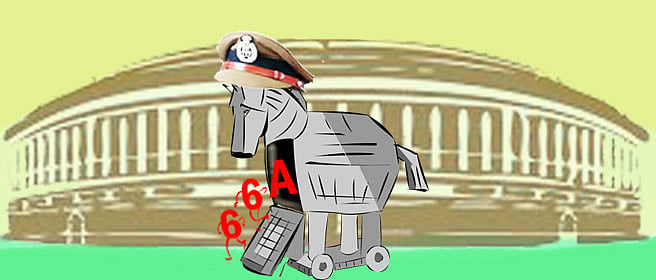

The plea argues that the government is trying to do through the new rules what it couldn’t with section 66A of IT Act.

“We see these rules as undermining the very essence of freedom of the press as far as digital media is concerned,” Siddharth Varadarajan, editor of the Wire, said on Monday after the Delhi High Court issued a notice to the Modi government on a plea challenging its new rules for digital media.

He was explaining why the Foundation for Independent Journalism, the trust which runs the Wire, along with MK Venu, a founding editor of the Wire, and Dhanya Rajendran, editor of the News Minute, had gone to the court against the Information Technology Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code Rules, 2021.

“The rules are creating a whole mechanism for government intrusion that is not envisaged by the constitution, and it is necessary to take a stand against this,” Varadarajan added.

Rajendran said, “These rules give the executive much more power than envisaged in the constitution. I think the government is working to spread this narrative that digital news media organisations do not have any kind of code of conduct or any kind of control which is not true.”

She explained that digital news organisations are already covered by defamation and penal laws. “We also work under any restrictions placed on press freedom under Article 19 of the constitution,” she added.

Appearing for the petitioners, advocate Nithya Ramakrishnan told the court that the new rules, particularly as they regulate digital news media, "go far beyond anything that is permissible in a democracy”.

She alleged that the government was trying to achieve through these new rules what it could not with section 66A of the IT Act, which was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015. The scrapped provision empowered police to arrest a person and jail them for up to three years for posting "offensive" content online.

After issuing the notice, a bench of Chief Justice DN Patel and Justice Jasmeet Singh listed the petition, filed on March 6, for hearing on April 16.

When the petitioners expressed their concern that the government might take coercive action before the next hearing, the court said they could approach the court in that case.

‘Misuse of IT Act’

The petitioners have argued that these new rules go beyond the remit of the Information Technology Act, 2000 under which they have been issued. They have pointed out that provisions of the IT Act don’t in any way seek to regulate or control digital news media, unlike the new rules. In fact, even section 69A of the IT Act doesn’t provide for regulating electronic content except when put out by a “government agency” or an “intermediary”.

In the court today, Ramakrishan said there was no dispute that intermediaries were different from news publishers. The court asked for examples of “intermediaries”, to which she replied that according to the government’s own categorisation, they included tech companies like Google, Facebook, Twitter. They don’t include digital news publishers, she added.

“We have faith that the judiciary will hear our point that 69A has been wrongly used to bring digital media organisations under the guidelines,” Rajendran told Newslaundry after the hearing. “We have explained to the court how upon merest complaint, central government’s interference is triggered on all manner of content, far beyond what is mentioned in 69A.”

‘Curbing press freedom’

Speaking to Newslaundry, Varadarajan argued that the government had formulated the new rules by “misusing” the IT Act, “which was never designed to deal with digital news media in any form”.

He said the new rules “completely” go against freedom of the press. Article 19 of the constitution does impose reasonable restrictions on press freedom, but they are defined by statutes. “The government doesn't have discretionary authority to decide what is acceptable and what is not,” he added.

Releasing the rules at a press conference on February 25, union I&B minister Prakash Javadekar had declared, “Press freedom is the spirit of democracy, but let me tell you that all freedom has to be responsible freedom."

The petitioners have further argued that Part 3 of the new rules seeks to impose government oversight on digital news media and a code of ethics under vague conditions like “good taste”, “decency”.

The rules prescribe a code of ethics for digital news media and prescribe a “three-tier structure”, including self-regulation and the appointment of a grievance redress officer, to ensure that it is adhered to. The third tier, which is the most contentious, is a committee of government officials tasked with overseeing the code’s implementation. It has the power to block content or order the publisher to modify or delete it.

“The government committee is the apex of the process. Not only is it the final stop for any so-called grievance that is escalated through levels 1 and 2, the government can also act suo moto,” explained Varadarajan. “So it doesn’t even need a real grievance, the government may just decide it doesn’t like certain content.”

He noted that the recent instance of a Manipur journalist being issued a notice under these new rules showed how they can be used.

Paojal Chaoba, editor of the news website Frontier Manipur, was issued a notice under the new rules on March 2, less than a week after their introduction. The notice, which objected to a weekly show on the website, Khanasi Neinasi, was withdrawn following an outcry by the media fraternity.

Afterwards, Javadekar issued a clarification on the notice sent to Chaoba, which the editor had described as “intimidation”. “The rules are very clear that a district magistrate does not have the power to issue such a notice,” the minister told Hindustan Times. “The mechanism is mostly self-regulatory and only in very serious cases can they complain to the ministry.”

Varadarajan said their petition was driven by the apprehension that these new rules would have grave implications, on digital news media and beyond. “We fear that this is going to have a chilling effect across the board, on freedom of press and the right of the ordinary citizens to express ourselves through the digital format,” he said.

Is Section 66A coming back?

Is Section 66A coming back? All you need to know about Section 66A

All you need to know about Section 66A