My quest for Remdesivir in Mumbai: Who has the antiviral drug?

I managed to procure six vials for my father, but outside the normal channels. Private hospitals say their supplies from the administration fall far short of the requirements.

It was the night of April 17. My father had tested positive for Covid and had been isolating. He had been feeling breathless since evening and checked his oxygen saturation levels on an oximeter.

At around 11 pm, 86 flashed on the tiny screen. A reading of 94-95 is usually considered normal – and this wasn’t.

For the next 30 minutes, we made frantic phone calls to hospitals across Mumbai. We finally secured a bed that had just been vacated at Niramaya Hospital, a private Covid facility in Kharghar near Navi Mumbai.

At 11.45 pm, we were huddled in the open-air waiting area at the hospital. Covid patients sat on long benches, keeping a good distance from each other. Their families watched anxiously as a doctor in a PPE kit checked their oxygen levels. My father’s reading was 77. He was rushed to the ICU.

As I filled an admission form at the reception, the son of a patient, who had been admitted that morning, was handed a prescription to procure six vials of the drug Remdesivir.

“Do you know where I can get it?” he asked the receptionist. No, the receptionist said, their in-house pharmacy had run out of stock and the hospital was having a hard time procuring it, too. When I was handed the same prescription the next morning, asking the same question seemed futile.

Remdesivir is an antiviral injectable drug which is reported to have had some success in the treatment of Covid. India’s Drug Controller General approved it for emergency use last June. Though studies have not shown concrete evidence of its efficacy in treating the virus, it’s being widely used in India to treat hospitalised patients with moderate to severe symptoms in the early stages of their hospitalisation. Dr Randeep Guleria, the director of AIIMS in Delhi, said it was “no magic bullet” but it “may be able to reduce hospital stay”.

The drug has been in short supply across states, including Maharashtra, for the past few weeks. It’s now priced between Rs 899 and Rs 3,490 by the seven manufacturers in the country, and can sell for Rs 8,000, even Rs 12,000, in the black market.

Maharashtra has a daily requirement of 70,000 vials, according to chief minister Uddhav Thackeray, who has requested the central government to increase the state’s allocation. Alongside its scarcity, Remdesivir has also found itself at the centre of a political tangle, with politicians found hoarding and distributing it on multiple occasions.

‘Sorry, we’re out of it’

On the morning of April 18, prescription in hand, I began the search for six vials of Remdesivir. Family members, friends and neighbours joined me, heading to pharmacies and hospitals while I sat down with huge lists of Remdesivir distributors that were being circulated on WhatsApp. Thirty phone calls later, I had nothing: the numbers were either busy or switched off, or the voice on the other end said, “Sorry, we’re out of it.”

I then tried the helplines of Cipla and Hetero, two of the half a dozen manufacturers of Remdesivir in India. Both said the drug would next be available in only four or five days.

When I called the Panvel Municipal Corporation, under which Kharghar falls, I was told that the supply of Remdesivir was routed through the district collector’s office only to hospitals. The corporation did not have the drug and was not authorised to help people procure it. The state government’s recently launched helpline to facilitate the procurement of Remdesivir was unreachable.

Equipped with the prescription and a form required to procure the drug from a government facility, my uncle then stood in a queue outside a Mumbai hospital’s pharmacy. An hour later, the stock ran out. My uncle was not able to buy it.

Finally, the director of Niramaya Hospital requested an emergency stock of 20 vials from the district administration and divided it among the most critical patients. This included my father, who was administered two vials of the injection as recommended.

But we weren’t out of the woods yet. We needed four more vials, and I spent the next day on the phone. One vial came to us from an acquaintance who had just been discharged from hospital after recovering from Covid and had one dose of Remdesivir left. The other three finally came from a family friend working in the pharmaceutical industry; he pulled strings to get them for us at a higher price.

But my story is just one among thousands being shared and posted on social media, of people struggling to respond to SOS calls while an overstretched healthcare system reels under shortages.

Private hospitals run around for ‘crumbs’

After facing a relentless dearth of the drug first-hand, I decided to try and figure out why Remdesivir was not available even in hospitals, the only institutions allowed by the government to make the drug available to patients.

Under a new allocation system introduced by the Maharashtra government about a week ago, Remdesivir can be allocated to private hospitals only through the district collector’s office and not directly through manufacturers. Each hospital will get doses proportional to 10 percent of their active cases through a distributor decided by the district administration.

I spoke to doctors at multiple hospitals under Panvel Municipal Corporation in Raigad district. All of them said the stocks they received were inadequate for their daily requirements.

Dr Amit Thadani is the director of Niramaya Hospital in Kharghar, which has a daily requirement of over 50 vials of Remdesivir to treat patients on life support. He told Newslaundry that his hospital was allocated just five vials on April 23, after receiving 20 doses on each of the preceding two days.

“We are not getting Remdesivir to the amount that is required,” he said. “Instead we’re just being told [by the district administration] that it does not decrease mortality so don’t use it.”

From his experience, Thadani said, Remdesivir has been found to decrease the duration of a patient’s stay in hospital. “These people are playing with patients’ lives,” he said. “Every single bed is important during a pandemic and you would want to get patients well fast so that the beds are vacated for the next lot of patients, isn’t that equal to saving lives?”

Adding to the confusion was that distributors assigned to hospitals were changed every day. Some of them were located far away, so it was not feasible to deploy manpower to procure small quantities of the drug. “It’s like they’re throwing crumbs here and there and we’re running about helter-skelter trying to collect them,” he said.

Dr Philomena Isaac, the medical administrator of MGM Hospital in Panvel, echoed some of Thadani’s concerns. MGM Hospital has 250 Covid beds and currently requires between 80 and 90 vials a day. They received only 10-30 vials a day last week, which Isaac described as not “adequate at all”.

Isaac agreed that Remdesivir is not a life-saving drug and that in its absence, other drugs are used to treat patients. However, she said, it does play a role in reducing the length of hospital stay. With low supplies, MGM Hospital has to prioritise patients while administering the drug, asking other patients to procure it themselves from outside.

“Some patients do manage to get it,” she said, “but we don’t know how.” On why supplies are low, she said, “They haven’t told us. We read things in the newspaper...It is possible that it’s all going into black.”

At Asha Multispeciality Hospital, Criticare Hospital, and Om Navjeevan Hospital, all of which fall under the jurisdiction of Panvel Municipal Corporation, doctors said the stocks they receive fall short of their requirements. Om Navjeevan Hospital added that they had not received any Remdesivir for three days last week.

Nidhi Chaudhary, the district collector for Raigad district, whose office oversees the allocation of Remdesivir, told Newslaundry that allotments are made based on the total number of oxygen beds in the hospital and the total number of active patients on life support.

When asked about shortages faced by hospitals, Chaudhary said, “When doctors talk about shortage, they should be 100 percent sure that there is no other medicine available for patients apart from Remdesivir.”

She argued that when it was known that there is a shortage, it was a doctor’s “moral responsibility” to save patients' lives with the available medicines. “I have, in fact, appealed to doctors to not recommend it when it is in short supply and give it only to the cases that could probably have some impact because of Remedesivir,” she said, adding that it was being recommended “blindly”.

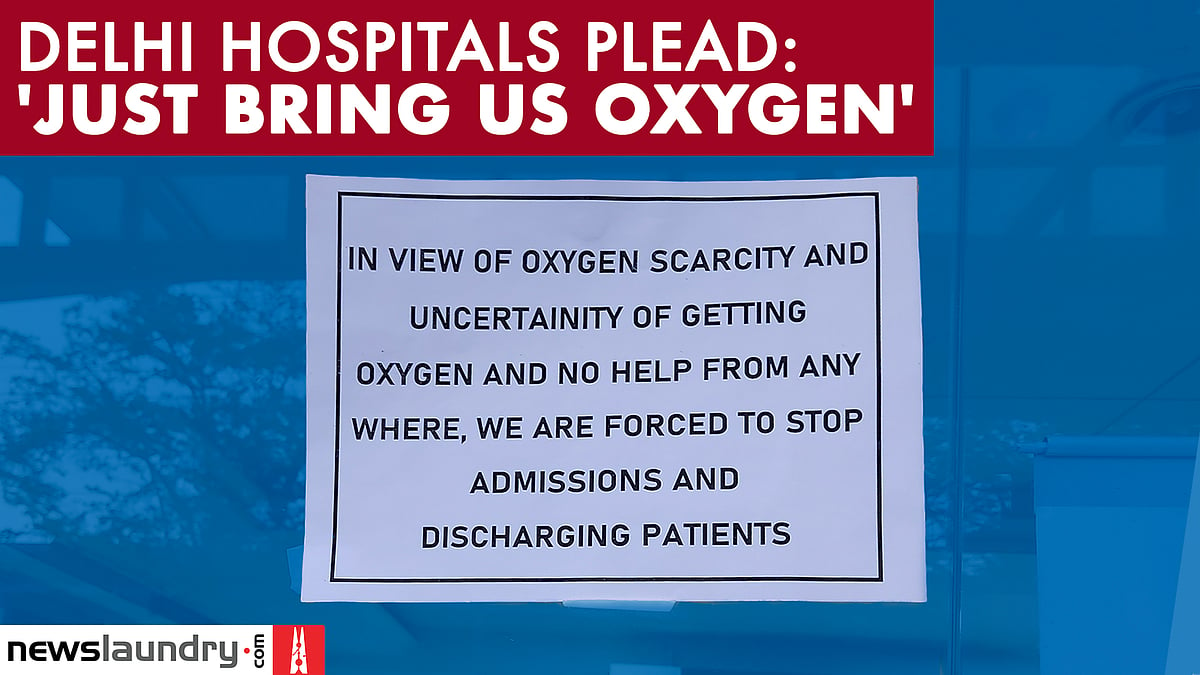

'Just bring us oxygen': North Delhi hospitals plead for help

'Just bring us oxygen': North Delhi hospitals plead for help