BJP’s David vs TMC’s Goliath: Why the TMC was the lesser evil

Amit Shah, Yogi Adityanath and Modi himself were identified as leading a force whose ascent to power would lead to 'gondogol', meaning trouble.

From the beginning of the epic eight-phase election schedule to the exit polls a month later, the talk was on whether the BJP would successfully topple the Trinamool Congress, led by incumbent chief minister Mamata Banerjee, and come to power in West Bengal.

Large sections of the media, from their headquarters in Noida near Delhi or Lower Parel in Mumbai, had built up the expectation that this was going to be it: the Bengalis, and especially the Muslims and sickular, libtard “bhadralok” among them, were going to be shown their place, which was at the feet of the Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan brigade.

The great and glorious leader of Hindu India, prime minister Narendra Modi, was himself leading the charge with an army of cabinet ministers and chief ministers led by Amit Shah and Adityanath. They had the money, muscle and means, the full control of key government institutions and the media.

What could possibly go wrong?

Plenty, it seems. Now that the results are in, it’s clear that this was a wave election. The TMC won 213 seats and the BJP just 77.

Other parties are wiped out. The Congress and CPIM, which fought the poll together, have zero seats. These two parties – which between them had reigned over Bengal from 1947 to 2011 – have fared more poorly than their new ally, the Indian Secular Front led by Muslim cleric Abbas Siddiqui, which managed to win its first seat in the constituency of Bhangar where Abbas’s brother, Nawsad Siddiqui, representing the Rashtriya Secular Majlis Party, was the winner.

The only other seat in the 294-member assembly to have gone to someone not from the BJP or TMC was Kalimpong in the Darjeeling hills which was won by Ruden Seda Lepcha of the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha’s Binay Tamang faction. He had contested as an independent.

The high-voltage BJP campaign, with its rhetoric aimed at religious polarisation along Hindu-Muslim lines, did polarise the electorate – just not to the end that the BJP and RSS (which has become increasingly involved in political campaigning in the past seven years) would have intended. The BJP’s appeal for votes on the basis of “Hindu khatre mein hain” (Hindus are in danger) – expressed through statements such as the one by its Nandigram candidate Suvendu Adhikari that Mamata would turn West Bengal into “mini-Pakistan” – did not find purchase with a majority of the population, including a significant percentage of Hindus.

The attempts to polarise Muslim votes away from the TMC by bringing in Muslim parties also backfired. The AIMIM has drawn a blank and the ISF has been largely rejected by Muslim voters of Bengal.

The TMC ended up increasing its vote share to 47.9 percent, up from 44.9 percent in 2016. The BJP vote share has increased from 10.1 percent to 38.1 percent. The CPIM vote share has shrunk from 19.7 percent to 4.7 percent and the Congress’ from 12.2 percent to 2.9 percent.

A large chunk of the Left-Congress losses were the BJP's gains. However, the TMC clearly held on to its vote share and was further bolstered by a section of the Left and Congress vote migrating to it. Faced with an imminent threat from what increasingly looked like an invasion rather than an election, many Left and Congress voters who traditionally disliked or even despised Mamata for one reason or another chose to side with her.

The resulting increase of vote share accounts for the double century that TMC scored. Had those votes gone the other way, as the BJP – which had garnered 40.7 percent of the vote in Bengal in the 2019 Lok Sabha poll when the TMC got 43.3 percent – had hoped, the race would indeed have been a lot tighter.

There are certain typical Bengali words that express the apprehensions that voters, including fence-sitters, had about the BJP that caused them to prefer TMC. One could hear them in conversations all the time. The word “gondogol”, meaning trouble, was a key one. The BJP, led by an array of tough-talking leaders with past criminal cases against them, starting from Amit Shah, Adityanath and Modi himself, was rightly identified as a force whose ascent to power would lead to “gondogol”.

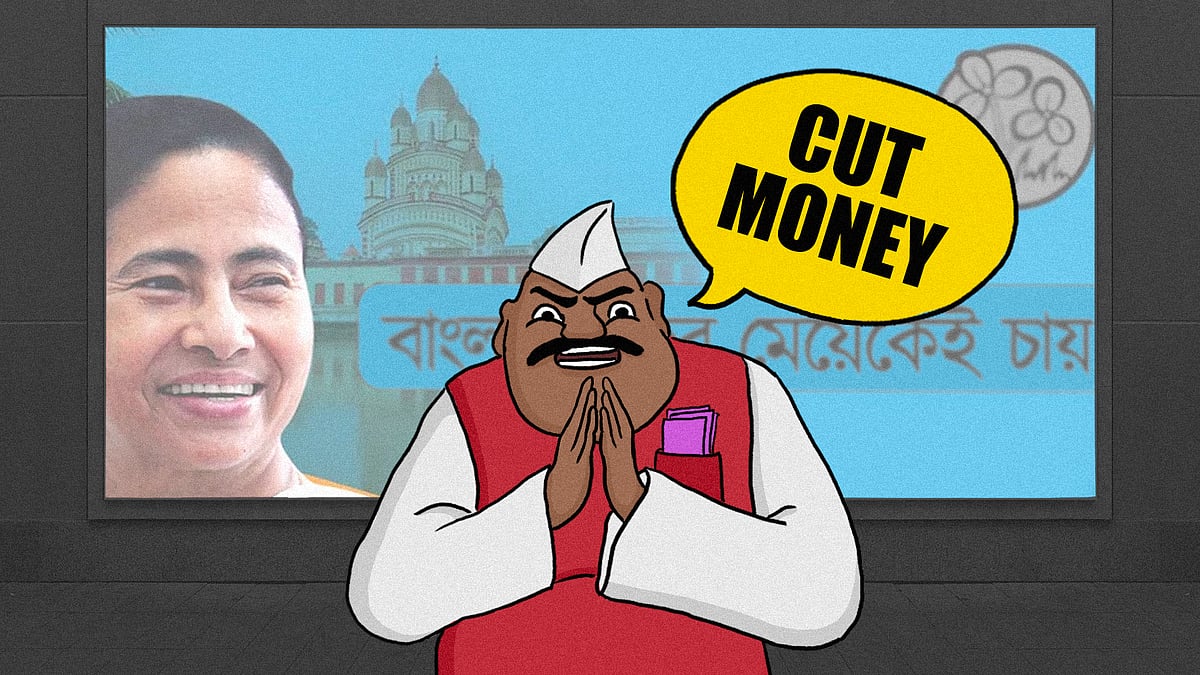

People don’t like gondogol; they like to get on with their ordinary lives, even if they are angry that the local TMC man is a small-time thug who extracts cut money from welfare schemes. At the end of the day, despite that, people live in peace and harmony, and they usually get at least some benefits from the welfare schemes.

Bengal’s election result is Narendra Modi’s personal failure

Bengal’s election result is Narendra Modi’s personal failure

Cut money and tolabaji: How deep is the anger against Trinamool?

Cut money and tolabaji: How deep is the anger against Trinamool?The TMC thus appeared as the lesser evil. Kolkata civil society and intelligentsia (who in earlier polls were generally dismissive of TMC), fearing a return of communalism in Bengal for the first time after Partition, also rallied and launched campaigns such as “No Vote to BJP”. Singers and actors did songs and music videos. Artists created artwork. Diverse sections of society came together.

The absence of a local BJP leader as a face against Mamata was also a big minus for the saffron party. The BJP hoardings showed Modi. The contest was billed as Modi vs Didi.

Well, Bengal has chosen Didi.

The TMC projected Modi and the BJP as outsiders, and this rang true. There was no sign of any local BJP leader having any role beyond genuflecting before Modi and Shah. Dilip Ghosh, votary of cow urine and beating up Jadavpur University students, who leads the state unit of the party, did not even contest the election. The BJP’s old guard, including Rahul Sinha and Tathagata Roy, had already been sidelined. BJP union minister Babul Supriyo and the party’s Tarakeshwar candidate Swapan Dasgupta were Delhi-based and had no connection with people even in the constituencies where they contested, and lost.

It was finally left to TMC turncoats who joined the BJP in recent months and years, people like Mukul Roy, Suvendu Adhikari and Arjun Singh, to make a fight of it for the BJP. The battle in the end was not between TMC and BJP; it was between TMC and ex-TMC, or TMC A-team vs TMC B-team. In that battle, TMC A-team prevailed, even if captain Mamata Banerjee herself, somewhat surprisingly, lost from Nandigram.

That defeat does nothing to dent her appeal. On the contrary, it rallies more sympathy in her favour. Her decision to take a risk, lead from the front, and boldly challenge Adhikari in his home turf had set the tone for the electoral battle that was to follow.

The slogan of "Khela Hobe" (game on) had caught on. The accident or attack that led to her fighting the entire election from a wheelchair sharpened the sense of a doughty underdog battling a big bully. In the context of Bengal, she was the big leader, and TMC for many was the big bully, but the BJP with its army of union ministers and chief ministers arriving practically every morning from Delhi (Amit Shah held more than 60 rallies and roadshows while Modi held 15), the open hostility of sections of the Noida media, and the deployment of more than one lakh paramilitary soldiers in combat fatigues armed with automatic rifles increased the sense of a David vs Goliath battle with TMC cast as David.

Goliath has been felled. Despite the ongoing tragedy of the Covid second wave, the news of BJP’s juggernaut being halted has brought a ripple of joy for secular and liberal forces in West Bengal and across India. It has demonstrated that one woman in a wheelchair can stand up to the might of all the BJP and its entire ecosystem, and win.

The country and its Constitution, and the lives of its people who are dying from misgovernance, can be saved.

Khela Hobe.