The larger loss of Sushil Kumar’s fall from grace

His double Olympic wins led many to believe that he had finally redeemed the lost glory of a misunderstood sport.

The first wrestling match I watched in Delhi was almost two decades ago. It wasn’t in a stadium, but not far from one. The bout took place at a ground in Vijay Nagar and ended with the defeat of a promising young wrestler; he was undone by a deft move from his opponent in the closing moments.

He broke into tears, much to the bemusement of the crowd. The moment belied the sturdy frame and the measured skills that had defined him until then. In a few minutes of mud-clay akhara kushti, his practised agility and trained muscularity were not prepared for the heartbreak of a loss.

As a tribute to the great sport, the moment revealed the range of emotions at work beneath the placid mien and the fierce will to win. I never knew the wrestler’s name, nor how he went on to pursue the sport.

Barely three kilometres from the ground stands the Chhatrasal Stadium in northwest Delhi’s Model Town. It’s here that two-time Olympic medallist Sushil Kumar began training as a 14-year-old, graduating from mud pit bouts to mat-wrestling at the highest level of international events. Early this week, the crime branch of the Delhi police brought Sushil to the stadium to recreate the crime scene as part of its investigation into the murder of Sagar Dhankhar, a 23-year-old junior wrestler.

Along with his aides, Sushil is accused of being part of a group that thrashed Sagar to death in the parking lot located outside the stadium premises. The probe has so far hinted at a turf battle for dominance within the wrestling circuit and the underbelly of a wrestler-gangster nexus in the national capital region.

It might not be news for long-time watchers of the wrestling scene in the capital. But it still touches a raw nerve because of how far it strays from the cultural imagination of wrestling in the native milieu. Even with all modern amenities of mat practice and world-class coaching, Chhatrasal still blends the traditional ethos of wrestling with its modern form.

Akhara, for instance, is still the preferred word for the training ground. The touching of feet of senior wrestlers and regarding trainers as gurus persist as time-honoured mores. It’s even seen in how iconic wrestlers like Sushil are addressed.

“He's something of an icon now, never referred to as Sushil Kumar but with the honorific Sushil Pehelwan (wrestler) or just Pehelwanji,” as Jonathan Selvaraj wrote in ESPN.

Almost three decades ago, anthropologist Joseph Alter, who in his youth was also a part of an akhara in India, gave an ethnographic account of how, in North India, a wrestler’s body could mirror identity and ideology. The training seeks to attain goals of physical strength and skills as much as it seeks to nurture a moral personality.

Alter’s work, Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India (1992), showed that in some cultural settings, wrestling is meant to develop as a way of life: a way of seeking character through purity and self-discipline, even celibacy in some cases. Moreover, even while using modern food supplements, most wrestlers stick to traditional dietary practices and rural ideas of strength-enhancing food. Sports journalist Rudraneil Sengupta’s work Enter the Dangal: Travels through India’s Wrestling Landscape (2016) has a few glimpses of the pattern.

The ideas of reverence for a pehelwan’s training and conduct, and the resultant expectation of loyalty from the younger wrestlers, is somewhere embedded in its old-world appeal, more so in the akhara ethos. The clear distinction between a demonstrative activity like bodybuilding and a competitive sport like wrestling isn’t merely technical. It could be traced to how kushti had a philosophical life much beyond the arena. Alter’s work gave more reasons in seeing this difference. The themes of character-building and values of guru-shishya traditions still find resonance in the current crop of leading Indian wrestlers like Bajrang Punia.

In this backdrop, the crime-wrestler nexus and the fight for fiefdoms seem far more odd. But in the national capital, the linkages between wrestlers and intimidation activities run deep, and so do perceptions. From gangsters and land-grab mafia barons to even banks seeking loan recoveries, the imposing presence of wrestlers has been used for different purposes. It has been normalised to the extent of a stereotype, much to the disadvantage of a number of wrestlers who have never been part of this seedy world. It has also reinforced a rural-urban bias in how the wrestlers are seen in city’s fitness training circuits.

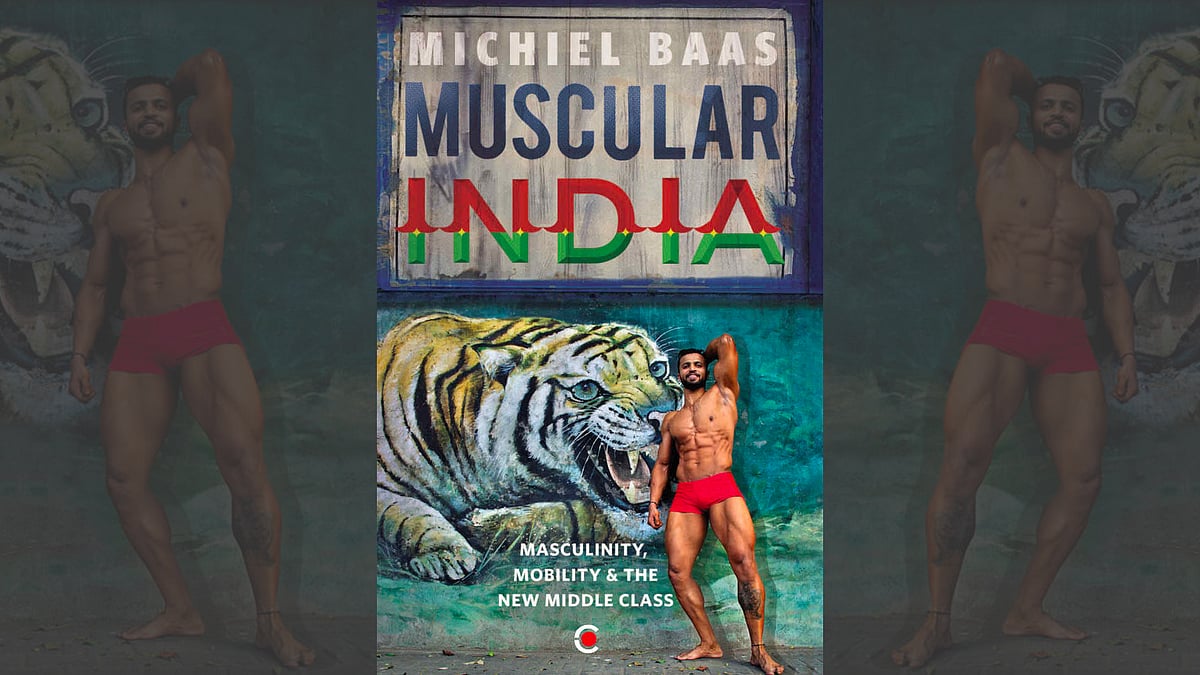

In Michiel Baas’s book, Muscular India: Muscularity, Mobility and the New Middle Class (2020), a sociological study of fitness industry in different Indian cities, this aspect was observed in Delhi-based gyms.

“Within Delhi-based gyms, the wrestler’s body was rarely appreciated,” he wrote. “The association with village backgrounds, rural masculinities and the potential of encountering ‘such men’ as ‘rowdy types’ and ‘who make their living as bouncers’, sets wrestlers apart from the trainers that clients encounter in the gym. The latter are men they trust with providing guidance in terms of workout routines and diets, and who would often even function as lifestyle coaches.”

Michiel Baas’s Muscular India is an important contribution to the understanding of urban India

Michiel Baas’s Muscular India is an important contribution to the understanding of urban IndiaTo an extent, the international laurels won by Indian wrestlers challenged such stereotypes in the national capital, or at least the generality of it. The latest accusations against the biggest name in Indian wrestling doesn’t do that image makeover any good. Although the Wrestling Federation of India is itself a body riven with feuds and factions, it was quick to grasp that the deadly brawl has badly hurt the image of Indian wrestling. It might give a new currency to long-held stereotypes of a Delhi wrestler.

This comes at a time when despite the global acclaim won by Indian wrestlers, the sport isn’t adding a wider pool of wrestlers. In his book, Baas talked about learning that many akharas in Delhi have given way to commercial gyms. Newspaper reports from different parts of the country sometimes tell the same story about akharas; some even talk about an ageing generation somehow trying to keep a tradition alive.

One such report in the Times of India, on old wrestling enthusiasts struggling to keep the sport alive in the city, carried the headline “These could be the last wrestling bouts in Madurai”. A 2019 photo essay in the Guardian talked about passionate mud-wrestlers in an austere akhara in Mumbai. “No one here cares if you are Hindu or Muslim or what caste you belong to. If we worship anything, it is the body,” a 23-year-old wrestler was quoted as saying. The essay observed that besides their dedication to the sport, one incentive that drove young wrestlers was the prospect of getting a government job under the sports quota.

A two-time Olympic medallist, Sushil had no such anxieties about securing a financial future. He was already employed with the Indian Railways, and was also serving on deputation as a sports officer on special duty in the Delhi government. As the most successful individual Olympian from India, fame could have opened many doors of access and earning for him. He was one of the rare wrestlers who endorsed products too.

At the multipurpose Chhatrasal stadium, as the ESPN report detailed, he had his share of admirers, and a group of women athletes lauded him for ensuring safety. Steeped in the traditional guru-shishya mould of Indian wrestling, he never missed the honorific of “mahabali” in addressing his coach Satyapal. Sushil went on to marry his coach’s daughter, making his ties with the former ace wrestler personal too.

However, a group of admirers at the stadium seems only a part of the larger story. The fear of the wrestler’s clout and the brewing resentment against it are also talked about; the reactions to Sushil varying widely with different sets of athletes.

In the last few years, Sushil could be seen in two parallel worlds. One was inhabited by an ace Olympian still practising hard, and that’s how he improved upon his bronze at Beijing with a solver at the London Olympics.

The second was inhabited by a stalwart often finding himself on the wrong side of a controversy. In 2016, he was at loggerheads with the Wrestling Federation of India about his claim to represent India when Maharashtra’s Narsingh Yadav had won the quota for the category. In a dramatic turn of events, Yadav failed a dope test and the needle of suspicion pointed towards Sushil. The conspiracy theories gained a lot of currency. One year later, within minutes of the completion of an “ill-tempered bout”, Sushil’s opponent Parveen Rana and his brother were allegedly assaulted by Sushil’s supporters. The FIR lodged in the case had named Sushil as an accused in the assault.

Sushil’s eagerness to have unquestioning sway over Chhatrashal was seen by many as his way of ensuring dominance in the Delhi wrestling circuit. The emerging details about either Sushil hobnobbing or swinging his affiliations between rival Kala Jatheri and Neeraj Bawana gangs seem like another sordid tale that was waiting to be told. To add to that, the maze of property and eviction disputes, and the resultant ego clash with a defiant young wrestler training at Chhatrasal, sums up everything that can go wrong with a sport fighting hard to shake off disrepute in the capital.

A grainy video of Sagar’s death purportedly shows Sushil beating the junior wrestler with what seems to be a hockey stick. In a way, the switch from grappling skills of a world class wrestler in the arena to the thuggish certitude of inflicting pain with a stick captures the seedy side of the sport in the national capital. Ironically, not long ago, many believed Sushil had redeemed wrestling’s lost glory in the country. That wasn’t to be. Far from any international win, that heartbroken, tear-filled and defeated wrestler in that mud pit of Vijay Nagar was much more edifying in his passion for real contest.