Journalists in rural Maharashtra still have jobs, but no income. Why?

They don’t get salaries but commission for ads they book for their newspapers. And there are few ads to get in the pandemic.

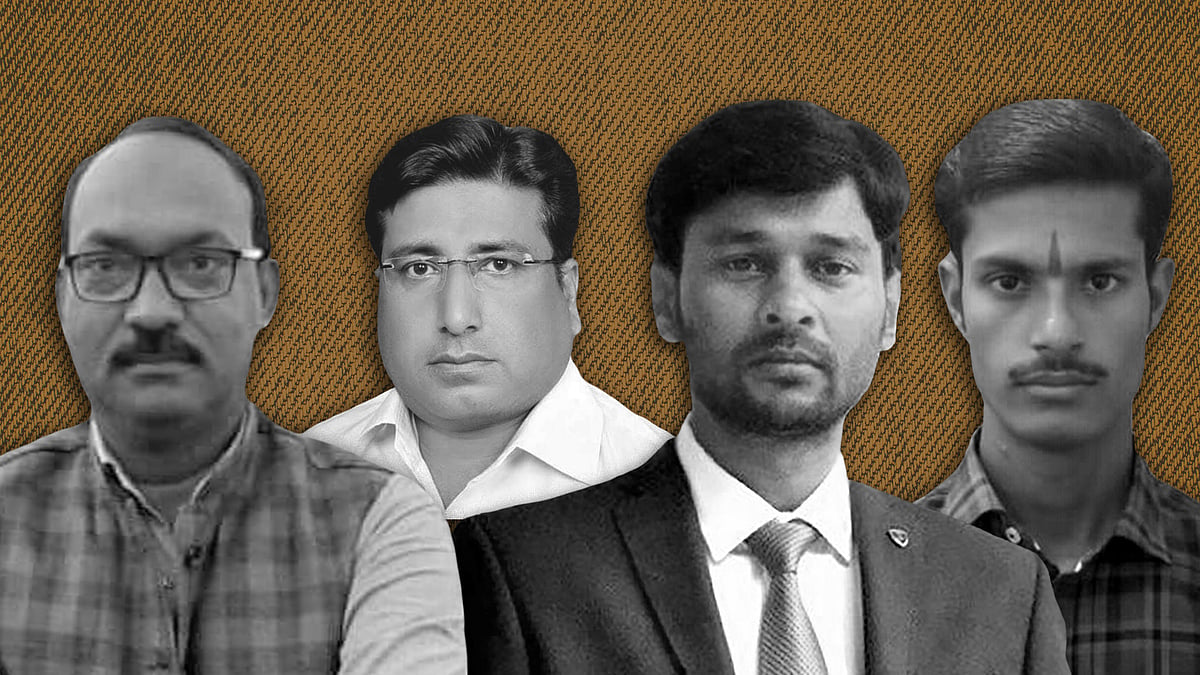

“Can I meet you in the evening?” Mahadev Kale, 45, a journalist with the Marathi paper Dainik Loknayak in Maharashtra’s Beed district, replied when we asked to speak with him one early June morning. “I am out at the farm with my goats.”

Herding goats is Mahadev’s “side job”. He takes out his flock in the morning and gathers news from Beed’s Kaij taluka through the day, that’s how he provides for his wife and three daughters aged 18, 15 and 13. Or did, until a year and half ago when the pandemic hit and his irregular income from the reporting job almost dried up. His precarious situation has only worsened this year: since Beed was locked down on March 24 to contain the spiralling pandemic, he has not been able to sell any of his 12 goats.

Mahadev would likely have been able to cushion the financial blow if he drew a regular income from his newspaper. But he isn’t paid for newsgathering, let alone a monthly salary. He is paid for the advertisements he brings for the paper.

This is a norm in the language press in Kaij, where newspapers don’t retain reporters on their payrolls, but instead pay them a 15-20 percent commission for every ad they bring. It is a practice that has left local journalists across rural Maharashtra struggling to make ends meet in the middle of a pandemic.

The ads are issued mostly by municipal bodies and local politicians, on such occasions as birthdays, anniversaries, inaugurations or festivals such as Diwali, Sankrati, Ambedkar Jayanti, and Shivaji Jayanti.

The pandemic has dealt a hammer blow to this revenue model. A number of newspapers in Beed have stopped their print editions owing to the lockdown. Those still printed struggle with distribution in the absence of transport. At the same time, ads from politicians, hotels and local businesses have decreased in number because of the pandemic-induced cash crunch.

Gautam Bachute, 40, who works for the Marathi daily Pudhari, pulled up outside a temple in Dhakephal village, Kaij, on a bike borrowed from a local police inspector, one of the many public servants, politicians and social workers in his extensive network. He is facing a grim financial situation, despite this network. With no regular ads to book for his paper and no side job, Gautam has had to borrow money from friends to support his family of four.

“We have had to worry about rations and water at home in the recent past,” he said. “Those of us who work solely as journalists have had a lot of problems.”

Before the pandemic began, he would bring his paper ads worth Rs 25,000-50,000 per month. On occasions like Diwali, when ads flourished, this would sometimes go upto Rs 1 lakh.

He received a 16 percent commission for each ad, or Rs 8,000-10,000 per month, but often got the money after a five-six month delay. In May, he didn't secure a single ad. On June 1, booking an ad for a local politician’s birthday earned him a commission of around Rs 2,300.

According to DD Bansode, a reporter with Prajapatra and former president of Sakriya Prakar Sang, one of four journalist unions in Kaij, the local reporters now get only about 10 percent of the ads they did before the pandemic. “Newspaper distribution is shut, no one gives advertisements and there’s no payment,” he complained, “journalists have suffered the most during Covid.”

Pudhari has laid off people on its rolls during the pandemic, but Gautam’s job is “secure”, because they do not have to pay him a salary. “They removed the ones who are paid. They can’t remove us because we earn for them. If we didn’t get them business and just published news, it wouldn't work,” he explained.

In rural Maharashtra, working journalists may be armed with press cards and phones full of contacts, but the unstable ad model means they can’t rely solely on the profession for an income. So, having a “side job” like Mahadev’s is the norm rather than an exception. Teaching, farming, rearing cattle and running small businesses are some of the common “side” jobs, although Covid has disrupted them as well.

“This is my passion, my hobby. But I don’t depend on journalism for my economic needs,” said Bansode, who is also a high school teacher. “Ninety percent of the journalists are in other professions. You cannot depend on your income as a journalist to run your house.”

‘All doors are closed now’

Balasaheb Jadhav, 32, reports mostly on crime and political events in Kaij for the Marathi daily Adarsh Gaonkari. He also juggles with two other jobs, driving an autorickshaw and wedding photography. He has three children to fend for. The money he’d saved for their education went into paying for his wife’s treatment for Covid in two different hospitals.

“All doors are closed now,” Balasaheb said. There are very few passengers to ferry in his auto, and the lockdown has stopped weddings for now. “Jahirat is especially hard to come by these days,” he added, meaning ads, “people haven’t even paid for the Diwali ads I got last year.”

He explained that the system of local reporters booking ads for their newspapers works on “trust and goodwill”, so it usually takes a couple of months for payments to arrive. “We would keep visiting the advertiser earlier to ask for payment but even that’s not possible now,” he said, adding with a flash of smirk and shake of his head, “When we call, some of them give the excuse that they are in quarantine.”

Yet, instead of helping them in these tough times, Mahadev said, their newspaper publishers keep calling them every other hour to ask for the ad money that hasn’t been paid. The full amount for the ad is first given to the reporter, he explained, and then goes to the publisher who disburses their commission back to them.

Mahadev would make a few extra bucks by securing two-three district court notifications for his paper daily, each earning him Rs 150 in commission. Now that the courts open sporadically, if at all, this source of income has dried up as well, but he continues to travel to Kaij after herding his goats each day, gathering news for his paper.

Ranjeet Ghadge reports for Pune Express and Dainik Aattach Express, and works as a farm labourer too. Covid has harmed both his jobs, and the money is not enough to support his family of seven. “I haven't received an ad for three months. When we’d get ads, at least we could manage our households a bit,” he said.

Operating in grey areas

It is an open secret among rural journalists that this dubious and unfair revenue model is quite prone to material and ethical corruption: for kickbacks, unscrupulous reporters and their publishers bat for or against local politicians, officials, and business.

“Of course, there are reporters for whom it is a business,” said Mahadev, “to blackmail officers and get money out of them by threatening to write news that exposes them.”

Balasaheb chipped in, “Sometimes such things have to be done.” He explained that sometimes the only way to get ads from local leaders or officials is to keep writing about their inaction. He recalled writing about a gram panchayat project worth Rs 1,000 crore, work for which had not been completed. “After writing about it five-six times, I got an ad from the panchayat for Rs 5,000 and some of the work for the project was restarted as well.”

Glancing through recent reports by Balasaheb and Mahadev, we found that while they have regularly reported about local politicians giving ration kits to people and patients recovering in government Covid care facilities, they have also pointed out the lack of facilities and resources at rural health centres during Covid.

The ploy of criticising politicians and public servants to get ads out of them doesn’t always work. “If we write news, they will give ads. Advertisement is the soul of these things. But if we write something against someone, they may not give us ads,” explained Gautam, “they may give it to other reporters who write good things about them.”

At the same time, Bansode pointed out, “even if a politician gives you an ad you can’t write only positive news about them. People get to know. You have to write both types of news.”

Why are so many still in the profession?

“If you look at the whole of Maharashtra, the highest number of local newspapers are published in Beed, at least 50,” said Bansode, pointing out that the district is the home ground of such prominent political clans as the Mundes. The majority of reporters we spoke to mentioned securing an ad on the death anniversary of former union minister Gopinath Munde, breaking their dry spell.

Some journalists continue to work in the rural press despite the contrived revenue model and not getting paid for their reports for a sense of power and the label of “patrakar”, or journalist, said Mahadev. “We aren’t officers, but they still call us sahab. Sometimes we don’t have to go through the chain of bureaucracy to get personal work done and we also get it done quicker for those in need.”

For him personally, however, he said, “there is a social angle as well”. Having worked with multiple NGOs focused on relieving farm distress for over a decade he was drawn to journalism to highlight their grievances.

Indeed, every local reporter in Kaij continues to work for their own set of reasons.

“This is my skill. I can’t do anything else,” said Gautam, who is determined to continue working as a journalist in spite of his current situation. “It could get better tomorrow, no?”

Pictures by Tanishka Sodhi and Diksha Munjal.

‘If this is a war, just give us the armour’: Why journalists in Maharashtra are protesting

‘If this is a war, just give us the armour’: Why journalists in Maharashtra are protesting  Missing from headlines: How the Adityanath regime is going after local journalists

Missing from headlines: How the Adityanath regime is going after local journalists