Should Indian media constantly call out the powerful for peddling falsehoods?

It can’t be otherwise.

How does a half-truth or an outright lie become a "fact"? When it is uttered by a politician or a celebrity and amplified unquestioningly by the media.

That is one of many challenges facing India's media. How often should you call out the powerful when what they are saying is patently untrue?

The media in the United States did not spend much time debating this when they regularly fact-checked every utterance of former president Donald Trump, who had a habit of being rather liberal with facts. Leading newspapers and TV channels regularly ran fact-checks to inform readers and viewers of the exaggerations and lies that were routinely mouthed by their president even as they had to report what he said. In some instances, television networks chose to stop live relays of his speech when what he said was particularly problematic during the height of the coronavirus pandemic.

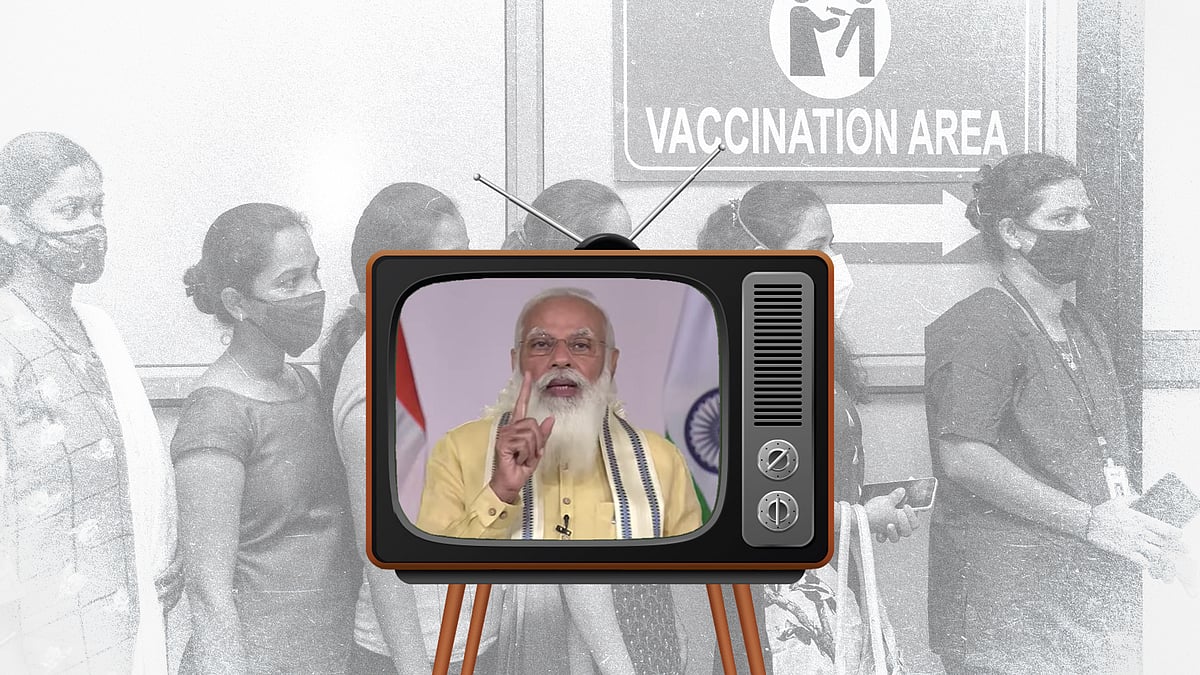

We have not seen the media doing this in India. The pronouncements of the powerful are routinely telecast or reproduced in print. The next day, an opposition politician might point out that what was said was untrue. If that is reported at all, it will pass without notice. Or an expert could write an article on the edit page contradicting the politician. This again would be read only by the converted, so to speak. Thus, what lives on in public memory is what the powerful person has said.

Does fact-checking the public pronouncements of the powerful even matter?

According to Prof Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University and author of the recently released 2021 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, many Indians thought that much of the misinformation about the pandemic often came from the top. In an edit page piece in the Hindu, he writes, "Study after study around the world has found such 'network propaganda', where misinformation is spread by some top politicians, nakedly partisan news media who cheer them on, and well-organised communities of political supporters active on social media and messaging applications."

Nielsen's advice to the Indian authorities if they want to check misinformation is to " take a cue from the fact that much of the Indian public clearly recognise that misinformation often comes from the top", and "spend less time worrying about activists, journalists, and Twitter".

Indians already paid a heavy price for believing the messages that "come from the top" earlier this year when we were told that the coronavirus crisis was behind us. The media ought to have been more vigilant and could have amplified the voices of those advocating caution and pointing out that even countries with good healthcare infrastructure in the West had been hit by a second and even a third wave of the pandemic. Given the poor state of India's health infrastructure, there was simply no place for the message of Indian exceptionalism that was being propagated.

The impact of the second wave was horrific and sudden only because the warning signs were not heeded. For the media, the story was so stark that it could not be ignored. From the oxygen crisis in Delhi to the half-buried corpses along the Ganga, no self-respecting media house could look the other way and ignore what was going on. As the editors of Dainik Bhaskar, one of the largest Indian newspapers, told Newslaundry, you had to report what you saw.

The paper's Gujarati edition, Divya Bhaskar, was one of the first to track the discrepancy between the official death toll and what its reporters saw on the ground. Since then, apart from Dainik Bhaskar, several mainstream English language papers such as the Hindu have been doing the data crunching to put forward the real number of deaths. Experts and biostatisticians had been predicting that the real numbers would be at least 10 lakh and not the 3.9 lakh officially acknowledged by the government. The persistent stories in different media have not just reiterated these projections, they suggest the total could be even higher.

Yet, there has been no acknowledgment so far from the different state governments, or the central government, that the death data needs drastic revision.

The Reuters Institute report focuses on misinformation with regard to the pandemic. But in the last month, we have seen other forms of misinformation such as about India's vaccination policy. We still have to estimate how much the union government's constantly changing vaccination policy has cost the country in terms of avoiding hospitalizations and deaths and also contributing to vaccine hesitancy.

We are constantly being told that this government has been exceptional in its vaccination policy and if there have been hurdles they have been placed by the obduracy and unreasonable demands of the opposition-ruled states.

We are also told by none other than the prime minister that this is the first time India is producing vaccines. On June 7, in his televised address to the nation, Narendra Modi said, “If you look at the history of vaccinations in India, whether it was a vaccine for smallpox, hepatitis B or polio, you will see that India would have to wait decades for procuring vaccines from abroad. When vaccination programmes ended in other countries, it wouldn't have even begun in our country.”

Is this true? As Jacob Koshy politely points out in the Hindu, this view of India's vaccination policy is "at odds with the facts”. He goes on to list the smallpox vaccine and the polio vaccine as examples of how India manufactured vaccines even before Independence.

That is not all. In his speech, Modi also said that since 2014, that is, since his party came to power and he became the prime minister, under the Indradhanush programme launched by his government, the percentage of children being vaccinated had increased from 60 percent to 90 percent. Yet, this too flies in the face of facts as according to the latest National Family Health Survey, none of the 17 states and five union territories surveyed had touched 90 percent in child vaccination. In fact, reports Koshy, only five states – Himachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka, Goa and Sikkim – exceeded 80 percent and only Himachal Pradesh touched 89 percent.

Why should this embroidering of history and facts matter? Because if they are not called out, this is what millions of Indians will believe, that only now is India "atmanirbhar", is producing vaccines indigenously and that the current government has given a boost to routine vaccinations too.

All this then flows seamlessly onto June 21, when India is supposed to have broken a "world record" in vaccinating over 86 lakh people in a day. Actually even this so-called "fact" is not true. But the reality of how this even happened is what makes the apparent achievement that the government boasted about more interesting.

For even as various ministers were busy crediting the prime minister and thanking him profusely for this achievement, the story of how it came about was already unravelling in the media. Supriya Sharma in Scroll exposed how the vaccination numbers were noticeably low in the states that hit a high mark on June 21 and that most of these states were ruled by the BJP. For instance, on June 20, Madhya Pradesh had vaccinated only 692 persons. Yet on June 21, it administered 16.9 lakh doses only to sink back to under 5,000 the very next day.

Although initially most mainstream newspapers ran uncritical frontpage stories on this “achievement”, in the days that followed many of them, including the Hindu and the Times of India, were more sceptical. They ran the data of the vaccine shots administered in the days before and after June 21. The figures spoke louder than words: the one-day miracle was only possible because stocks had been hoarded in previous weeks in some states.

The media also pointed out the huge discrepancy between the availability of vaccines, which will not exceed 40 lakh even if the Indian manufacturers operate at maximum capacity, and the requirement to maintain a daily target of 80 lakh or more. Where is the rest of the supply coming from? The government has yet to answer that question.

Then there is the myth of the "free vaccines". Unless constantly reminded, people forget that all vaccines have been free in India, from the smallpox one to BCG to polio. So providing Covid vaccines free to Indians is neither new nor an exceptional achievement of this government.

The reason such fact-checking is even noticed today is because it did not take place sufficiently in the past, and particularly over the last seven years. This has contributed to myth building, to the belief of one leader being not just invincible but also infallible. This myth has helped him and his party ride through multiple mistakes and bad policies that have placed such an enormous economic burden on Indians, especially the poor, apart from mismanaging the ongoing pandemic.

Calling out those who get free airtime merely because they are in power is the duty of a free press. It cannot be otherwise.

Are the reasons Modi gave for his vaccine policy reversal valid?

Are the reasons Modi gave for his vaccine policy reversal valid?