Project Pegasus: Why didn’t diplomats’ surveillance cause a stir? Because it’s taken for granted

There’s anger over surveillance of an alleged sex abuse victim, journalists, and an epidemiologist, but snooping on diplomats is no surprise.

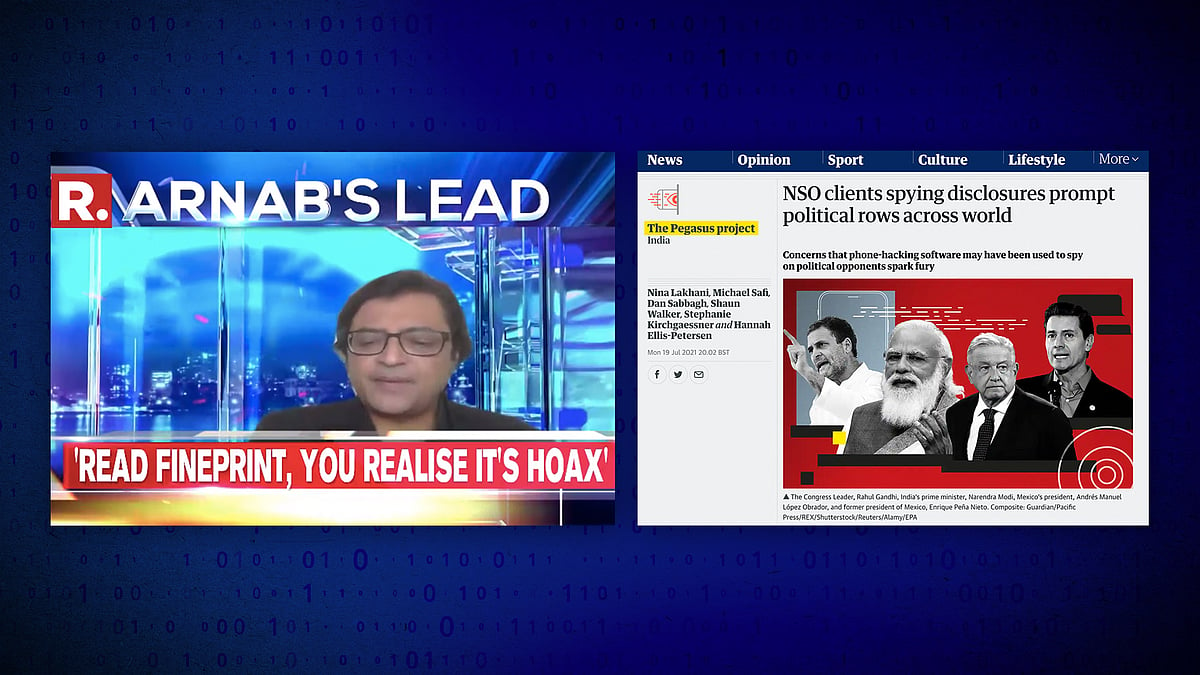

Horror at the scandal over the use of high-cost Israeli technology to snoop on journalists and others appears to have petered out in just a day or so in some sections of the media – at least in India.

The speed and sophistry with which that happened is ironic. It demonstrated that the government’s control on some of the media is so strong that allegedly targeting the phones of a handful of journalists was more or less superfluous. This is because most of those journalists only reach sections of society that are pretty much opposed to the government in any case. That was even more true in 2017-18, when surveillance is supposed to have been attempted.

Many others in India’s chattering classes not only believe the government’s version of things, they often revile the sort of journalists who were targeted as motivated, or agents, or anti-national, or all of the above. The strongest criticism of the Indian establishment over the Pegasus scandal came up on news platforms published abroad.

As for the alleged snooping on ambassadors and even a neighbouring prime minister, there was another layer of irony. Many of the journalists who had themselves been potentially targeted did not mention it. They argued that they had left out names and phone numbers of those whose phones might have been targeted for state security reasons.

They seemed to have accepted such surveillance as legitimate.

Phones or names associated with Kashmir were not mentioned in the stories that exposed the surveillance. That was intriguing, for it defies credibility that phones in Kashmir would not have been targeted.

And it was left to Suhasini Haidar to write in the Hindu that several New Delhi based ambassadors, including some of friendly countries, had been targeted for surveillance using the Pegasus software. She cited the French daily, Le Monde, extensively for that report. Some other news organisations also picked up the bare bones of the story.

Par for the course

Conversations with retired intelligence officers made it obvious that the surveillance of diplomats is par for the course. It has always happened, and since long before the telephone was invented.

One intelligence man even said that it was impossible to imagine embassies and diplomats without surveillance and information gathering of one sort or another. Diplomats too apparently take it for granted that this sort of thing is bound to happen, one way or another.

An intelligence man claimed that no country has surveilled other countries’ leaders and strategists as much as the US. He pointed to huge German anger when it was revealed that a US installation in Germany had surveilled several leaders, including German chancellor Angela Merkel.

Compared with that sort of scandal, he seemed to suggest, this was minor. Asked what the diplomatic fall-out of the Pegasus scandal might be, a retired intelligence officer said, without batting an eyelid: “They’ll give a demarche. The ministry will deny it. It’ll be forgotten.”

Indeed, there seemed little sign of a reaction from foreign diplomats in Delhi. Some in Pakistan raised concerns about the alleged surveillance of prime minister Imran Khan’s phone, but not about the country’s New Delhi based high commissioner.

Whodunit

In fact, each intelligence man I spoke to was more concerned about how these names and phone numbers got out. That was the only thing that seemed to surprise them about the entire issue. Each asked what I knew about how it came to light.

One top-ranking former intelligence chief expressed doubts about the theory that someone based in France had accidentally discovered it on the dark web. Although he is not a backer of the government, he seemed convinced that some powerful forces wanted a scandal publicised at this juncture.

All the intelligence men with whom I spoke emphasised that the set norms for surveillance – written authorisation by the union home secretary in each specific case – were strictly followed, at least as long as they had been in service.

(One retired security force officer, however, said that the authority to sanction tapping was delegated in some situations, such as Kashmir. He was sure a large number of phones there must be surveilled.)

This raises a huge question mark over how sanction could have been obtained to surveil constitutional functionaries and the family of a victim of alleged sexual abuse – if government agencies used Pegasus.

If the government was not involved, it raises questions over how such surveillance could have taken place in the country without the knowledge of agencies and forces meant to protect the constitutional and legal rights of citizens.

Amit Shah says ‘facts’ of Pegasus snooping are there for ‘entire nation to see’. What did we miss?

Amit Shah says ‘facts’ of Pegasus snooping are there for ‘entire nation to see’. What did we miss? Project Pegasus in media: 'Unacceptable', 'attack on democracy'...and a 'hoax', according to Arnab

Project Pegasus in media: 'Unacceptable', 'attack on democracy'...and a 'hoax', according to Arnab