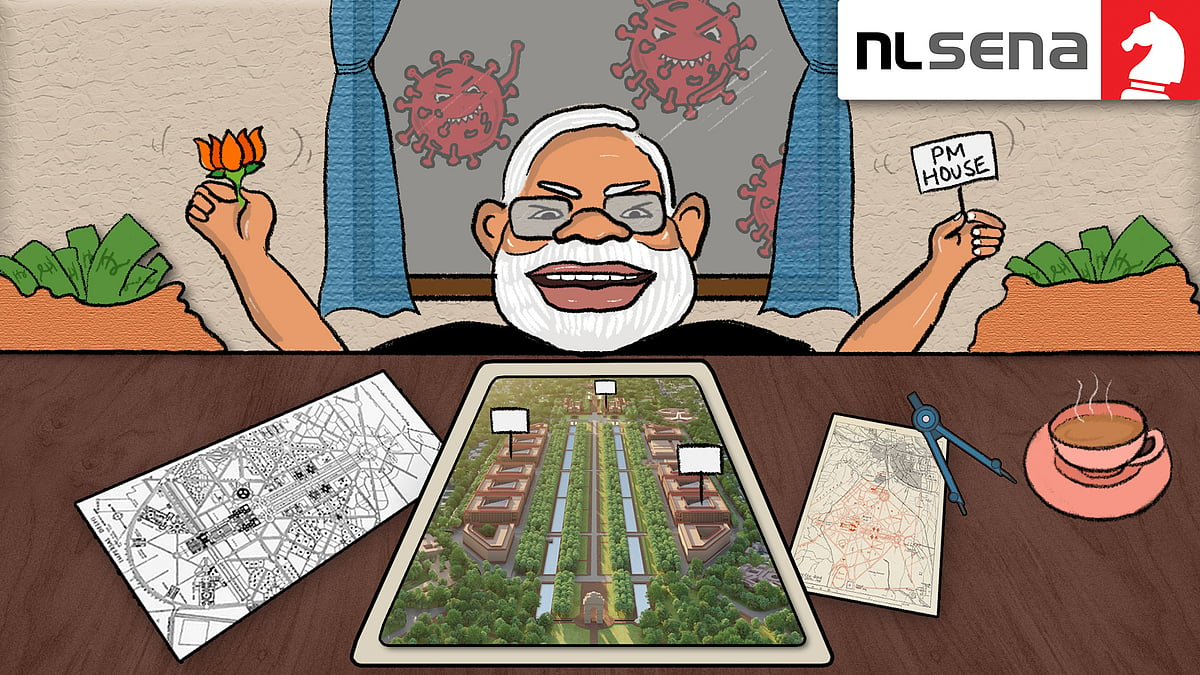

Bit by bit, trick by trick: How Central Vista became a reality

It was submitted for approvals as a series of micro projects to an array of committees brought to heel through cunning and brute power.

The parable of the blind men who visualise only the part of the elephant they can touch but never know the sheer size of the whole is an apt one for the Central Vista project.

By breaking up submissions into micro projects, no one can estimate any idea of the macro project itself or its collective impact on environment or heritage. The only people who know what the entire elephant will look like can be counted on one hand – essentially the architectural firm and the evaluation committee that chose it.

Every part of this project should have been submitted for approval to a standard list of required committees and agencies such as the Central Vista Committee, or CVC, the Heritage Conservation Committee, or HCC, and the Delhi Urban Art Commission, or DUAC. But submitting it in a million moving parts avoids easy tracking of what has been submitted, when or how.

This is why the new parliament has received environmental clearance as an “Extension of Old Parliament” but bizarrely applied for CVC approval as a “New Construction”. This is why the Rajpath lawns that have already been dug up have received CVC approval and heritage clearance but no environmental clearance. This is why only three of the new secretariat designs have been submitted and received CVC approval while all 10 have received environmental clearance. This is why the government has declared that the new parliament was somehow not part of Central Vista to avoid stricter environmental assessment. The list goes on.

As citizens, the objective is to understand the cumulative impact of the Central Vista project. This objective is placed in trust with the expert committees and judiciary to steer it in the right direction on heritage, environment and by-law compliance. By salami slicing the project, information might emerge, for example that 2,000 trees are being cut at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. But no one has the information to calculate how many trees will be cut for the full project. It could be 10,000 or 20,000 but it does not exist as a collective figure of loss.

Getting this collective understanding seems impossible because the sanctioning process, expert committees and constitutionally empowered bodies like DUAC have been damaged beyond repair. Their independence and ability to provide professional inputs have been trampled upon so severely that their certifications have become a robotic exercise in meaninglessness. They no longer possess the ability to act as trustees of citizens.

This is obvious when the Heritage Conservation Committee declares without embarrassment in the Supreme Court that Vijay Chowk is not part of Central Vista! Because if the obvious truth had been revealed that Vijay Chowk has always been a part of Central Vista since it was made 90 years ago, the new parliament would then have been subject to skyline restrictions.

Clearly what lies behind the evasions, opacities and chaotic moving parts are distinct strategies to subvert these committees and urban institutions. It is instructive to see what these strategies are and how they were put together. To do that it is essential to revisit the past.

In January 2016, an opinion piece was written on the need for a new parliament. This was possibly the first indicator of the government’s thinking on the project. Its author was architect Bimal Patel, favoured by prime minister Narendra Modi for several projects in Gujarat. To no one’s surprise, Patel would be awarded the consultancy contract three years later for the Central Vista project in a tender process riddled with enough improprieties to be challenged in the Supreme Court.

The years 2016 and 2017 would emerge as critical years for the Central Vista project.

A flurry of laws that smoothened the path

In these years, a flurry of laws and amendments were passed that would eventually prove critical to the Central Vista project and its chosen strategy of avoiding institutional scrutiny. They would loosen or knock out crucial controls, place key pawns on the chessboard in essential roles, and quietly activate non-operational laws.

August 24, 2016: Government land use FAR increased

The Master Plan 2021 is amended to increase the FAR of government plots across Delhi from 200 to 300 and of those in Central Vista from 120 to 200. However, the FAR of public land in Central Vista remains 120. This means more can be built on a government-use plot (200) than a public-use plot (120).

This immediately creates an imbalance between the two previously equal land use types so pressure is created by a builder-eager establishment to change the land use of more plots.

OPAAS dilutes the scrutiny process

The DUAC adopts an online system of submission called OPAAS. On paper, the move is meant to ‘modernise’ the sanctioning process and make it easier. In reality, these loose protocols start a dismantling of institutional safeguards that protect India’s cities.

In place of detailed models and signed drawings in hard copy that will stay in institutional records as a permanent submission that can always be referred to, only a quick upload of an online plan is required that may bear no resemblance to the final construction. PDF files of any quality can be submitted.

But the expectation that professional assessments can be made with a one-time look at a computer screen is an unreasonable one. DUAC’s minutes speak of the need to create guidelines, as the given submissions are of such poor quality that scrutiny, literally, cannot be done.

Three years later, in 2019, the Central Vista project will also operate under OPAAS. PDFs will be sent directly to expert committees like DUAC and CVC which will give their assent without application of mind (not possible in the absence of detailed drawings). Together with the absence of NDMC by-law scrutiny, it is impossible to know basic details like how large a construction is, how many floors it has, and how many trees need to be chopped. Till date, there is no scrutinizable, technical information in the public domain.

In July 2020, DUAC members will ‘approve’ the new parliament building by watching an online presentation as a shared slideshow.

May 18, 2016: Colonial law activated

The Government Building Act, 1899, was framed by the British empire that feared native rebellion. The provisions of this obscure piece of legislation that the law ministry itself describes as “pre-Constitutional”, allow the central government to build anywhere without permission of the urban local body. Over 120 years ago, it was meant for times of emergency. Today it would be called draconian and anti-democratic.

Despite the government’s much trumpeted abhorrence of colonial rule that made it target Central Vista in the first place, this old colonial law is activated. The only reason for this is to empower the Central Public Works Department, or CPWD, as an elected local body and allow it to sanction its own buildings.

The government makes sure this act is first referred to the law ministry that justifies its activation on the mindless ground that it hasn’t been repealed yet by any state. It is then used to order DUAC and other bodies to treat CPWD as a local body, a provision that doesn’t exist in their rulebook.

June 15, 2016: CPWD becomes local body

The 1899 colonial law does its job. CPWD buildings are “exempt from the regulation of Municipal Building Laws”. While NDMC, MCD and DDA derive their local body status from the 74th amendment and from their own Acts passed by elected assemblies, CPWD has neither. Yet, it starts sending proposals directly to DUAC, bypassing NDMC.

Deeply alarmed, DUAC members raise a red flag at a series of meetings. On May 24, 2017, the minutes detail their unease and specifically state, “It was observed that CPWD is neither a local body nor notified local authority and it cannot send proposals directly to DUAC.” They even add, “The issue is likely to have a ripple effect and, subsequently, other such agencies may also propose to exclude themselves from the purview of the local bodies.” (See picture below.)

August 21, 2017: DUAC ‘recognises’ CPWD as a local body

Nevertheless only four months later, DUAC complies and allows exactly that.

On the basis of the directive by the housing and urban affairs ministry on the 1899 law, DUAC recognises CPWD as a local body (see picture below). This so-called ‘recognition’ will have a huge impact on the Central Vista project’s regulatory journey ahead, making it smooth and comfortable without the ‘irritation’ of by-law scrutiny.

October 17, 2017: Government can build on any land

The Master Plan is amended again to permit land use for ‘Residential’, ‘Government Office’ and ‘State Bhawan’ (a brand new category invented for Modi’s pet project, Garvi Gujarat Bhawan) buildings, on all plots of various types of land, including and especially that marked for public/semi public use.

The state can now build without checks and balances. This blows a hole in the Master Plan. Each of these 2016-17 laws would play a critical role in the Central Vista project’s roll out, giving it a vital ability to achieve fait accompli and ensure no one would be able to delay it, stop it or protest against it!

Land grab of public-use plots by the state

The need for these amended Master Plan laws, faits accomplis, colonial acts, local body bypass and other strategies of evasion was prompted by the grand scale of the Central Vista project’s ambition.

Its first intent was the takeover of almost all public land in Central Vista and some plots of Lutyens’ Delhi – an intention that left planners reeling in disbelief.

Public land is a sacred and inalienable part of a city’s planning scape and occupies the grand spaces of most successful cities. Its prominence and scale is an indicator that prioritises the role of the people in a democratic state. Its shrinkage corresponds to the opposite.

That is why even though Lutyens had earmarked four key plots along Central Vista as ‘Public Use’ for prestigious national theatres, museums and cultural institutions, more plots of Central Vista were made ‘Public Use’ after 1947, to emphasize the public’s importance in the newly independent India.

Palaces became art galleries and three of Lutyens’ Big Four became the National Archives, the National Museum built in 1960 and the Indira Gandhi National Centre of the Arts, or IGNCA, built in the 1980s. Regrettably, it was the last big effort of the state to create premium institutions for the public. In 2000, Jawahar Lal Nehru Bhawan, which houses the external affairs ministry, grabbed the fourth plot.

Since then Lutyens’ Bungalow Zone too has been subjected to the ‘Slow Creep Land Grab’ strategy by the state, perfected by occupying individual public use plots and changing their land use plot by plot. JLN Bhawan along with Garvi Gujarat and Vanijya Bhawan, to list just three, were all built on public/sociocultural land use plots. Together, they make up 11 acres of precious ‘Public Use’ land taken by the state in the last three years.

Of these, JLN Bhawan took six years to even start construction due to “litigation and red tape”, proving that a land use change in a heritage precinct wasn’t always an easy walk in the park. In contrast, Garvi Gujarat was completed at warp speed in 21 months flat in 2016. But Vanijya Bhawan ran into obstacles with DUAC who refused approval, realising its FAR didn’t match its land use. The project had to be delayed until DDA could officially change its land use.

For the Central Vista project, therefore, strategy was upturned. Slow Creep became Knockout Punch!

The HCC was not even consulted on change of land use in a Grade-I heritage precinct despite clearly stated statutory requirements for their approval. HCC’s Clause 1.12 states that “change of use of such Listed Heritage Buildings/Listed Precincts is not permitted without the prior approval of HCC. Use should be in harmony with the said listed site.”

Instead a fait accompli was presented before anyone could object. It took only seven days in December 2019 for DDA to decide on the required call for objections on the land use change of 100 acres of ‘Public Use’ land to ‘Government Office’ use (including Lutyens’ Big Four, where all public institutions will be razed to the ground). By February 2020, it had already mindlessly, and in the face of public outcry, rammed through this conversion of land in one fell swoop to prep the Central Vista project for the path ahead. As many as 1292 objections were dutifully heard and fully ignored.

Unlike standard practice for global projects of this size and importance, it gave absolutely no impact assessment, no transport projections post change, no maps, no environmental consequences or any rational information to explain why it was essential to take away this massive chunk of public land.

A very casual count, therefore, shows about 120 acres of public land in Delhi’s smallest, most precious zone had been transferred to the state in the last three years. If JLN Bhawan is included, the total is around 128 acres. The prime minister’s new residence is on a plot that was ‘Recreational’ land use, meant for sports, parks, etc, and the new parliament will be built on what was once a park.

The point is not that land use can never be changed (with due process), but that over the last three years the balance has tilted aggressively against the public who have never been consulted before being stripped of their rightful space in the most precious zone of the city. Public land only in Central Vista is down to 15 acres today from 115!

Key strategies for the Central Vista project

At some point, key decisionmakers possibly understood that the normal sanctioning process would be too much democracy for the unprecedented ambitions of the Central Vista project.

Its requirements included demolishing iconic buildings, chopping down thousands of trees, building above the legally permissible skyline, imposing a new parliament, and grabbing almost all the ‘Public Use’ land in Central Vista.

There was no way it could be accommodated within the limits of existing law, especially in a Grade-I Heritage Zone. The risk of scrutiny and public damage would be too great.

Therefore, the critical strategies would be:

Use OPAAS to do away with detailed scrutiny.

Empower CPWD as a local body to avoid the real local body by-law scrutiny.

Salami slice ‘Out of Zone’ chunks to prevent one single heritage precinct that allows for more relaxed regulations.

Completely bypass specialist committees with independent professional members and public consultation or block any independent views from the minuted records. Pack them with government employees so orders can be executed without delay.

The brute force was reserved for the specialist committees. Strenuous efforts were made to pressurise or eliminate the independent, professional or public component in every technical committee.

The Central Vista Committee, the Heritage Conservation Committee and Delhi Urban Art Commission all have independent members. The housing and urban affairs ministry helming the project presented no way out. Whether by the tactic of members’ absence or packing in government employees as majorities or withholding detailed drawings or scrubbing crucial minutes of objections or impossible timelines, they forced their will upon these bodies and gave them no option of rejection. A fait accompli was the strategy to block all independent views and objections. By the end of it, the subordination and subjugation of these committees was devastating and complete.

HCC, for instance, is allowed to accept submissions only from NDMC, MCD and DDA according to its charter. The government decided to simply bypass it for approval of the project.

Yet, after the Supreme Court insisted the government seek its approval, HCC was forced to accept the project’s submission from CPWD even though its charter specifically rules it out! It dutifully ‘approved’ the new parliament as required, six days after the Supreme Court’s judgement on January 11, 2021. Even HCC’s required notice for public objection was ironically put out by CPWD – a measure of how irrelevant HCC itself had become.

Similar is the case with CVC. Its key mandate is to be led by architects and planners for “architectural control” of Central Vista. It has four non-governmental members who are heads of professional bodies of architects and planners. The other members are government employees from CPWD, NDMC, DDA, etc.

The decision to pass the change in land use of 100 acres of public land was taken at a meeting on March 9, 2020 with two days’ notice. One independent member was out of town. He sought deferment, his message was read out and the meeting carried on. The other wrestled for six hours, asking for “detailed facts” as clearly none were given. The record of this discussion is completely rinsed out of the official minutes that blandly record that approval was given in principle as land use change had been taken up with the “competent authorities”.

There is not a single word of discussion to record that CVC did its actual job of protecting Central Vista’s heritage, design and skyline!

The decision to pass the design of the new parliament too was forcibly taken on April 30, 2020 in the middle of the national lockdown to contain the pandemic when only government engineers and CPWD architects were present. Members, some of whom were senior citizens, pleaded for postponement to a less alarming time. The minutes document this fact, then state that the “national interest” of the project and its speedy “timescale” would not allow the committee to wait for lockdown to get over. Both were obviously rationales supplied by the ministry. The effect was that those who might have objected were absent.

A telling comment on the seriousness with which the government treats these bodies is that the head of the specialist committee to maintain architectural control and aesthetics over Central Vista at the time this project was passed was a road engineer from CPWD.

In subsequent meetings where independent members were present and protested, the minutes are conspicuous by their brevity. Every single meeting of the CVC with regard to Central Vista has a clean “No Objections” when it should have been raining objections. Clearly, the independent members were worn down by the pressure by the end.

DUAC follows the same trajectory. Minutes of its first meeting to discuss the Central Vista project record immediate objections on June 5, 2020.

Minutes of the second meeting on July 1, 2020 (when the new parliament was ‘passed’) with detailed objections were made public for a brief time before being quickly taken off. The minutes were then uploaded again with a sanitised version after a delay of a few days.

They now simply said the project was approved after a revised plan was received online and observations given. There was also no evidence that any of the objections on June 5 were addressed in the subsequent meeting. DUAC simply approved and made a few cursory observations on parking and security issues.

A member of the panel, architect Sonali Rastogi, put in her papers on “personal grounds” according to a news report from the same day the project was approved. The ministry accepted her resignation on July 2. The minutes report that she left the meeting “midway” for an “urgent medical appointment”. Rastogi has declined comment on her departure and subsequent resignation. Four members were present at this meeting who passed the new parliament.

And so, each of these well-practised strategies worked with orchestrated precision to achieve the impossible objective of approving blatantly illegal constructions in the capital’s Grade-I protected Heritage Precinct.

It’s interesting to see how the Supreme Court viewed these strategies that were taken before it via several petitions. Yet, having taken over all the cases filed against Central Vista in the Delhi High Court in March 2020, the Supreme Court’s 2:1 judgement on January 5, 2021 opined on only three main issues:

1) DDA’s sweeping land use change for the whole project,

2) Heritage related issues only for the new parliament and its clearance by CVC,

3) Environment related issues only for the new parliament and the Environmental Advisory Committee recommendation for its environmental clearance.

The split judgement offered completely opposite views.

The majority judgement based its opinion on the principle of ‘judicial restraint’ and accepted the government’s arguments that it must stay out of policy decisions. Based on this ‘restraint’, it did not probe whether these committees showed “application of mind” while reaching their decisions or followed due process. It took all clearances by various technical committees on face value as bona fide and independent. Relying on their technical veracity, it declared all three actions were just and proper.

The minority judgement, however, underlined the principle that if a process itself is fundamentally wrong, its results cannot be right. It based its opinion on the cognizance of faits accomplis faced by the technical committees and their lack of power to reject projects. It found this lack of application of mind and failure of due process so severe that it declared none of the three issues were just or proper and quashed all three unequivocally. It gave a 16-point recommendation for the government to follow. None of them has been followed.

The question of equity comes in here. Can an ordinary citizen aspire to defy the law with similar brazenness as the system scrambles to comply with the whimsical desires of men in power? Can a house owner in, say, Patna, bypass the Patna Municipal Authority? Can the state ride roughshod over the law it has created itself and are there two separate standards for the state and the citizen?

This lack of equity is the grubby reality of what the Central Vista project represents. Not a grand vision of modernity and ‘world class’ construction but a low tale of greed, cunning and brute power forcibly degrading the stewardship of ‘independent’ bodies until obedience is achieved. The effect on democracy, urban planning and constitutionally empowered institutions will be devastating in the years to come.

This is the second part of a two-part series. Read the first part.

Central Vista: The ignominy of building India’s parliament by breaking the law

Central Vista: The ignominy of building India’s parliament by breaking the law Central Vista: Why Modi’s New New Delhi isn't a shining city

Central Vista: Why Modi’s New New Delhi isn't a shining city Gujarat Model 2.0: The super elite’s magic wand to take over public space

Gujarat Model 2.0: The super elite’s magic wand to take over public space PM’s house on Rajpath: How a super elite is capturing Delhi’s land

PM’s house on Rajpath: How a super elite is capturing Delhi’s land