‘We can’t walk freely on our roads’: A day in the life for locals and shopowners at Singhu border

Business has taken a hit with the protests and the pandemic, and locals are looking forward to things returning to normal.

At Singhu border, between protesters and security personnel, is a stretch of land, almost 1.5 km long. For the past year, industries, shops, traders, commuters and residents on that stretch of land have been living in limbo.

Now, after prime minister Narendra Modi announced the repeal of the three contentious farm laws, this section of National Highway 44, or NH44, finally faces the possibility of free movement.

NH44 starts in Jammu and Kashmir and goes all the way down to India’s southernmost tip, Kanyakumari. It connects 11 states across a distance of 3,745 km, and is the longest national highway in India.

Singhu border, which falls on this highway, is barely half an hour away from central Delhi. It’s here that farmers set up camp last November, settling in for a year-long protest against the farm laws.

The region surrounding the protest site is marked by fields and small villages, the biggest of which are Singhu, Singola and Kundli. It’s also home to the Greater Kundli Industrial Area, which hosts an estimated 1,800 factories, most of which deal with cold storage, textile, printing, steel and export material.

Singhu border is also an important trade route and traffic is thick through the night, as heavy vehicles ply across the border.

Newslaundry spoke to locals and shopowners to ask them what life’s like, one year since the protest began.

No business, no sales

Aman Sharma’s “Kera Da Dhaba” stands right on the highway. Barely 50 metres is a Delhi police barricade, with the protest site about a km away. Vehicles are not allowed to pass through the barricade.

Sharma started this shop with his brother in 2019, after giving up their work as scrap dealers in Narela, where they live with their mother. During their first year of business, they sold only cold drinks, chips and biscuits.

“Then I realised that most truck drivers who stopped wanted some fresh food. So, in August 2020, after the first lockdown, we employed five more people, started a kitchen, and made fresh roti sabzi,” Sharma said.

Sharma’s dhaba is open through the day and night, seven days a week. Before the farmers arrived in Singhu last November, he would make Rs 10,000 a day and, on a good night, nearly Rs 30,000.

But the protest changed things. The police would no longer eat at his dhaba, he said, choosing instead to bring food from home. The barricade meant less footfall and traffic and by March this year, he fired all his employees except two: a waiter and a security guard. Suffering massive losses since the protest began, his debt now stands at Rs 20 lakh.

His shop is all but empty now, except for a few packets of chips.

Aman's dhaba.

“Previously, I never had time to sit down. It was that busy,” he said. “Now, there are days when absolutely nobody visits the shop.”

Sharma said he does not side with the police or with the farmers. “But I am looking forward to the farmers leaving,” he said. “My brother and I just want to make a decent living and feed our mother.”

Aman Sharma.

About 500 metres away from Sharma’s shop is the Sydney Grand hotel and Just Chill waterpark. The only hotel between the protest site and the police barricade, the 10-year-old Sydney Grand has 28 rooms, of which only five are currently occupied. The waterpark has been shut since March 2020 when the Covid pandemic began.

Namitha Pasricha, 35, the hotel’s receptionist, told Newslaundry she’s tired of arguing with the police.

“The farmers are sitting one kilometre away from here,” she said. “I don’t know what is the necessity for such a long barricade.”

The hotel had closed during the pandemic and subsequent lockdown, opening up again in August 2020. But when the farmers arrived in November 2020, business was badly hit.

“Back then, the barricade was closer to the protest so we kept the hotel open,” Pasricha said. “But after the Republic Day violence, they extended the barricade and we had to shut down again.”

Last month, when the Supreme Court made it clear that the farmers could not block roads “indefinitely”, a small service lane was opened up to reach the hotel. “But which guest will want to come here like this?” Pasricha said.

The Sydney Grand hotel.

Barricading at Singhu border.

Sydney Grand also lost 94 of its employees in the past year, with only six remaining. “Around 40 of our employees used to be women,” Pasricha said. “But after the protest began, women refused to take detours after dusk because those routes are long, without streetlights, and unsafe. So now, I’m the only woman employee here.”

Just where the protest site begins at Singhu, near the main stage, is Prem Prakash’s shop, which sells cold drinks and snacks. The shop was completely empty when Newslaundry visited, and Prakash, 52, sat outside on a plastic chair.

Prakash started this shop in 2007. Fourteen years later, in February 2021, he closed it down.

“There was no point keeping it open,” he said. “None of my supplies could come inside because of the police barricades, and I didn't make enough sales.”

He added, “In fact, all shops in this market, which runs for the next 500-700 metres on both sides of the protest site, shut down by March. There are close to 20 shops that shut.”

When asked about the impact of Covid, he said, “Covid didn’t affect us as much as this protest. Lockdown reduced sales but the protest completely stopped sales.”

Like Sharma, Prakash is now waiting for the farmers to leave to reopen his shop.

Prem Prakash.

Shyam Sundar, 50, told a similar story. He works at a clothing store around two km from the protest site. When Newslaundry met him at 3 pm, the store was empty, and Sundar said he hadn’t seen a single customer that day.

The store began in September 2020 with 25 employees. Now, it has only three, Sundar included. According to him, the shop is suffering from a loss of close to 90 percent but the owner has refused to shut it down.

On whether he’s angry with the government or the farmers, Sundar said, “I have not read the laws so I don’t know much. But all I know is that we elected this government to power and now they’re not bothered about our lives.”

Newslaundry also spoke to Sundar on the phone a day after the farm laws were withdrawn. He said, “I can’t wait for the protest to go back and for our shop to thrive.”

Shyam Sundar.

Villagers tired of the police

But at the village of Singhu, residents told a different story. Here, the villagers, who largely work as farmers, told Newslaundry they support the protest.

“Our life has not changed,” said Rama Devi, 35. “We still continue working on our land. Yes, transport is sometimes a problem but it is a small price to pay.”

Several villagers also said they’re upset with the Delhi police. “They stop us. They don’t let us go towards the protest,” Rama Devi explained. “We can’t even walk freely on our roads anymore.”

At Singola village, Newslaundry met a group of four women taking a detour around one of the police barricades, heading back home after getting their second Covid vaccine shot at a government school nearby.

“This walk would have taken us 10 to 15 minutes if the protesters and police didn’t block the road,” said Maya Devi, 40.

Maya’s husband works at a petrol station 200 metres away from the protest site. He used to earn Rs 16,000 per month but once the protest site and barricades appeared, sales went down and his salary was cut by half. The couple have three children, and Maya’s husband is the sole breadwinner.

Maya Devi.

Newslaundry also visited a slum along a small, dusty road, about 600 metres from the protest site. About 30 families from Bengal have been living here for the last 25 years. Most of them work as ragpickers, some of them as rickshaw drivers.

Two of the residents – Sabina Khatum, 22, and Sagar Khan, 18 – said they will feel “really bad” when the farmers leave, because many of them eat for free at the community kitchens set up at the protest site. Khan added that he often meets his “sardar friends” and plays video games like Free Fire for a couple of hours a day.

“I have a lot of fun with them,” he said.

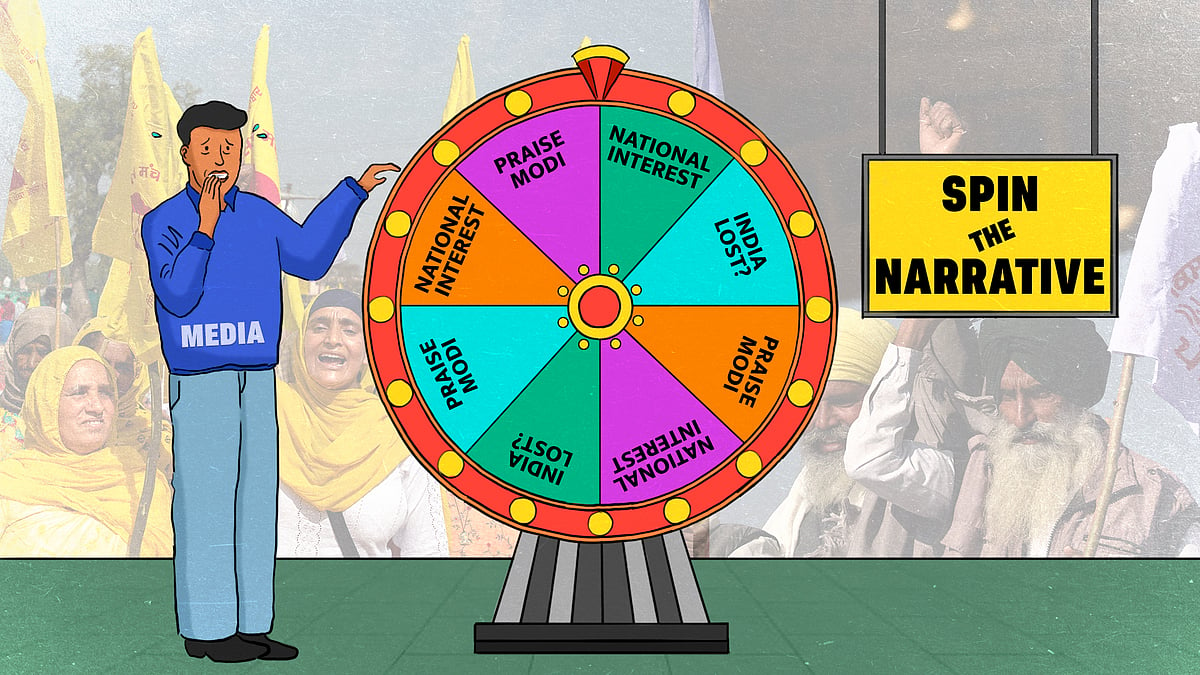

‘India lost, Congress won, Green Revolution derailed’: Primetime anchors anguished over Modi’s repeal of farm laws

‘India lost, Congress won, Green Revolution derailed’: Primetime anchors anguished over Modi’s repeal of farm laws

‘No plans to leave until the farmers do’: Nihang Sikhs on their year at Singhu border

‘No plans to leave until the farmers do’: Nihang Sikhs on their year at Singhu borderNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.