Farm laws fiasco: Two years of lost opportunity and lessons in how not to make policy

Given the scale of the problem, there was never any doubt that reform was urgently needed.

In September 2020, India enacted three laws that promised far-reaching reform of its vast agricultural sector. However, after more than one year of protests, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in an address to the nation last week, announced his decision to repeal them. While he apologised for his perceived inability to convince the protesting farmers of the benefits of the controversial farm laws, he made no reference, never mind offering a word of apology or mild regret, for his misjudgement of popular anger, nor for the year-long vilification of the protesting farmers, nor indeed for the heavy-handed policing of the protests and the loss of lives.

Between the flawed enactment of these three farm laws and the capitulation of the prime minister, there are serious lessons to be learned on how not to make and unmake policy in a democracy.

Reform was vital

India’s agriculture sector was relatively untouched by the opening up of the economy in the great liberalisation of 1991, which was probably less liberating than is often made out. Even 30 years later, the farm sector, with more than 50 percent of the population, generated less than 20 percent of the country’s GDP, and those whose survival depended on the back-breaking work of growing the nation’s food were seemingly condemned to be the proverbial poor cousins.

A series of policy blunders since 2016 led to a steady decline in the growth rate of India’s economy before it fell off the precipice, owing to the pandemic, with the government choosing to ignore much of the advice of economic policy experts. Rising rural distress, farm loan suicides, hunger, acute poverty, and joblessness are evidenced as clearly in this video clip about an ordinary citizen as in academic papers from economic experts such as Jayati Ghosh.

And so, given the scale of the problem, there was never any doubt that reform was urgently needed.

The rural economy needed modernisation that would only come from greater investment in farming technology, cold storage, transport infrastructure, insurance, finance and training and development in food technology. Farm incomes could rise only if the sector became more productive, and if vastly greater numbers of young people could be employed in industry and services.

Lesson for policy-making

But were these three farm laws the right policy response? And was it right to present them as the answer to the myriad ills that beset India’s vast pool of rural poor?

The answers were not forthcoming if only because of the Modi government’s we-know-best and one-size-fits-all style of governance that first became obvious with the demonetisation exercise of November 2016. There was never a white paper on the subject of the rural economy, no analysis of the possible effects on the poorest and most marginalised communities in India’s villages, and no consultation on the range of policy proposals that might have been suitable alternatives. Instead, the three farm laws were drafted and presented to Parliament as a done deal that was guaranteed to easily pass in the Lok Sabha because of the government’s solid majority.

In Parliament, discussion of the Bills was curtailed, criticism was dismissed as politicisation, and a plea for referral to a Select Committee was regarded as a time-wasting dilatory tactic.

The near-total lack of a consultative and deliberative approach in formulating far-reaching agricultural reform had two major effects. One was a degree of hubris and arrogance on part of the ruling party that the democratic will of the people (as expressed in the 2019 mandate) was being thwarted by a fickle opposition. A loss of trust in the government was another.

So when Mr Modi expressed regret that “a section” of the farmers could not be persuaded of the “benefits”, he was putting a gloss on the fact that the protesting farmers did not trust him. The reasons for this distrust are aptly captured in this clip.

The economist Kaushik Basu explains this loss of trust best when he suggests that ordinary farmers understood innately the trade-off that exists between the certainty that comes from intimate knowledge of what we have and the promise of an expanded range of choice that we might not be able to afford. Think of this as the common-sense preference for the bird-in-hand over the two in the bush.

The basic flaw in the Modi administration’s approach to policy-making is devising policy on the hoof and then presenting it as being in “the interests of the nation”. Even in his address last week, he said that he was withdrawing the farm Bills in the national interest, not in the interests of the farmers. Appeals to “think of the country” are typical of nationalist movements that seek to place ideas of the nation above the ideal of the welfare of every citizen. It is a crude attempt to sell to the poor a policy that will further impoverish them by suggesting that it is “good for the nation”. Many in India accepted the tremendous economic damage wrought by demonetisation because they bought into the myth that it would “purify” the nation of the evil of black money. By invoking the metaphor of sacrifice in a noble cause, Modi got away relatively unharmed by the disaster of demonetisation.

Even the decision to repeal the farm laws seems to have been taken on a whim and a caprice. There was no evidence in the prime minister's 19-minute address of any deliberation or discussion by the Cabinet. The announcement was a shock to senior party leaders as much as it was a pleasant surprise to the protesting farmers. Even foreign newspapers concluded that the u-turn was occasioned by the experience of bye-election losses and the electoral calculus of imminent elections in Punjab and Uttar Pradesh.

People-centric policies

When governments take big policy decisions “in the national interest” or for narrow party political gain, the interests of ordinary people take a back seat. When powerful leaders in positions of authority claim to act for the good of the country, they may well be working on behalf of the wealthy. The fact is that India gains in strength when its weakest citizens grow stronger. India gains when the poorest Indians gain, not the other way round.

As Barack Obama put it in the context of America, “The nation cannot prosper long when it favours only the prosperous”. And so it came to pass that the farm Bills were widely seen for what they were﹘a give-away to the rich corporate world of big business, the billionaire class who, under the new system, would control every aspect of the lives of the hundreds of millions of Indians who would have no choice but to live off the land.

Lost opportunities

Even as farmers celebrated the promised repeal of the farm laws, and as the ruling party’s faithful were busy tweeting their grateful appreciation to Mr Modi, the situation on the ground remained as dire as it ever was. India has a serious hunger problem, unemployment blights many families, and in rural communities seasonal unemployment has become worse due to falling demand and reduced spending power as a result of the pandemic.

These are problems that demand urgent solutions, and need the Union and the states to work together. Instead, in recent times, all we have witnessed is a stand-off between an obstinate government and farmers determined not to be marginalised by reforms which they see as a free-market solution that will leave them impoverished and at the mercy of a few big corporations.

Indians deserve better. There are lessons to be learned from the farm Bills fiasco that might show the way to a less tendentious policy-making culture where consultation replaces confrontation, and discussions and dialogue cut out discord and division.

'If our media was free, things would've been different': 300 days of farmer protests

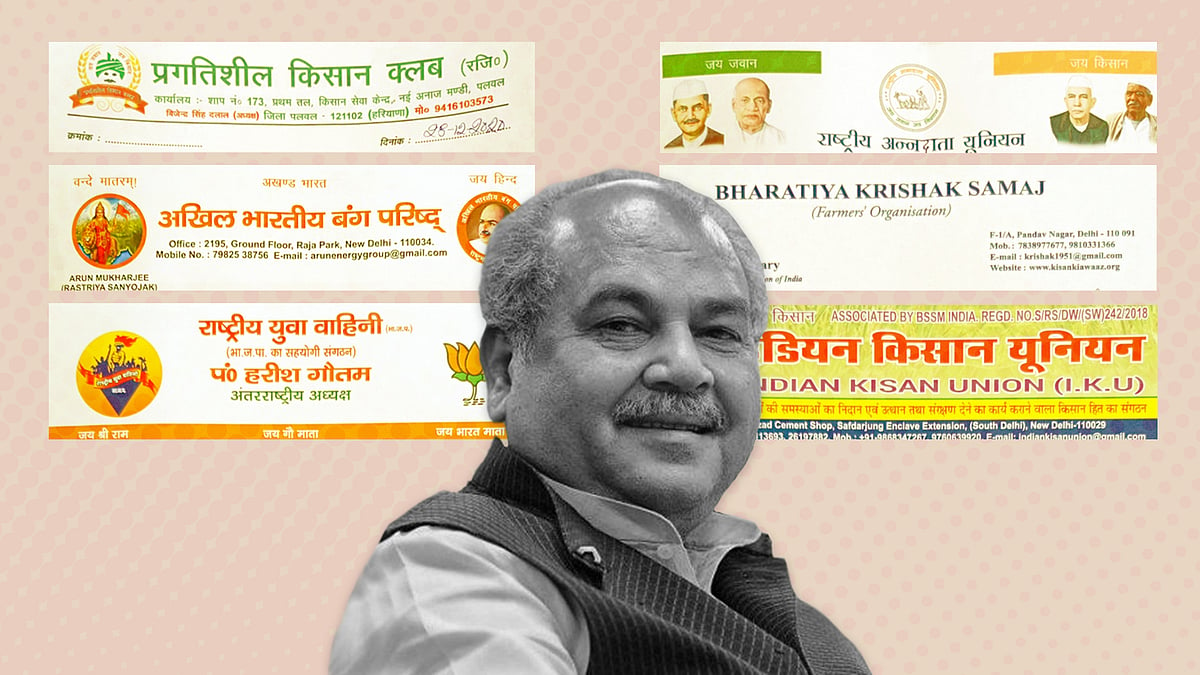

'If our media was free, things would've been different': 300 days of farmer protests Who are the ‘farmer leaders’ supporting Modi on farm laws?

Who are the ‘farmer leaders’ supporting Modi on farm laws?NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.