Looking at Central Vista through a different lens: How world class is ‘world class’?

It opposes the very core values that define 'world class'.

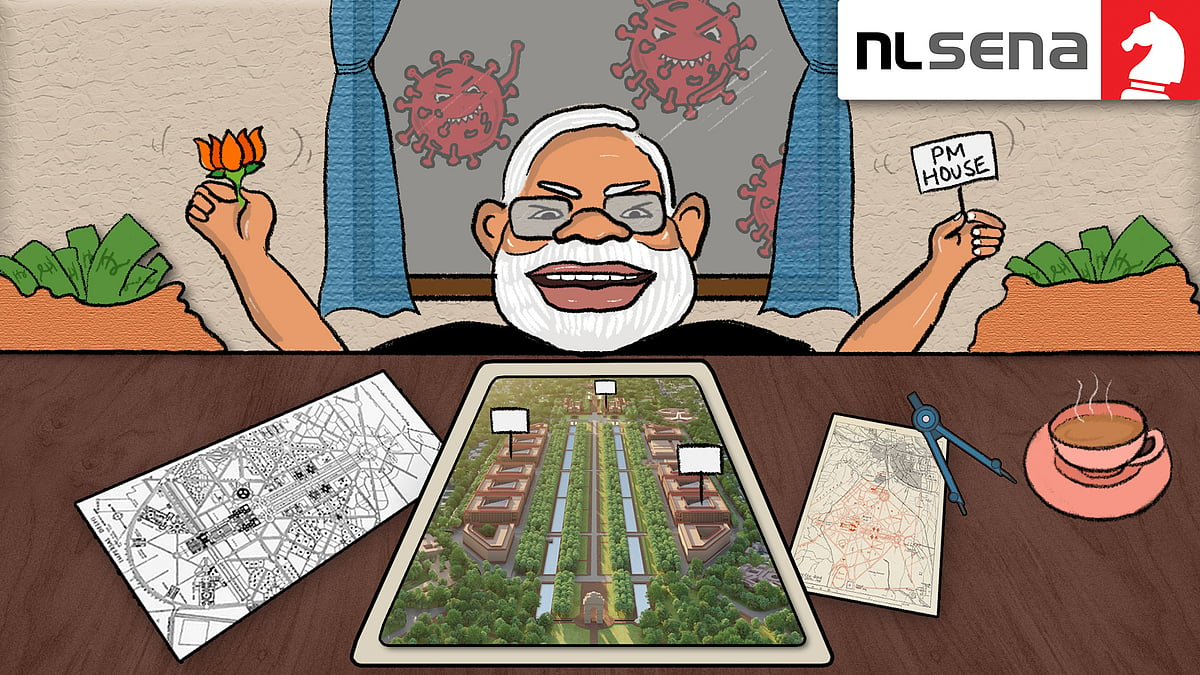

As the embodiment of the regime’s “New India” vision, the Central Vista project is a showcase of its core values. Its non-negotiable speed and decision-making display the key objectives New India stands for – excellence, and efficiency above all. In this soaring re-imagining of the country, “New India” is not merely a victor standing tall but a Vishwa Guru to the world.

As a “project of national importance”, therefore, it has an immense burden of expectation on it.

It is expected to be the “pride of the nation,” and seeks to build “Atmanirbhar Bharat” by fulfilling the vast democratic aspirations of the country. (“Hamare desh ke viraat loktantrik lakshyon ko sakar karne wala.”)

There is a single phrase that encapsulates all these ambitions on almost every web page and as uttered by every functionary of the state, from minister Hardeep Singh Puri to architect Bimal Patel to prime minister Narendra Modi himself.

World class.

This implies that not only will Central Vista be judged as such within India but also internationally – since it will conform to world-class parameters.

Yet state narratives aside, what does world class actually mean in the real world of design, architecture and urban planning? Is it good parking or more space? Is it the Google type gyms and cafes? Is it efficiencies of technology, the best materials or smart interiors? Is it traffic management and automation? Or is it something else entirely?

In feudal times of monarchies and empires, architecture was a heroic enterprise. Its visibility and opulence had an imperial purpose – to show the citizens where might and power lay. The Central Vista built by the British certainly fit that category.

Yet soon after, there was a paradigm shift in architecture, signalling the dawn of a modern era in which power lay with the people. In keeping with this progressive thinking, the elected rulers of democratic, independent India allocated over half of Central Vista’s plots to the public in the 1950s, thus reimagining the centre of our capital from authoritarian pomp to people’s space.

If we look at contemporary world-class global architecture to truly understand what “world class” means in today’s world, the first core value is clear.

Democracy is still as critical a statement of modernity as it was 70 years earlier. Public access, openness, decentralisation and democratising of power – these are the modern architectural creeds of today at the core of the best buildings in the world.

No longer are buildings monumental, reflecting power or a class system that denies ordinary people entry and reserves its best for a tiny minority of big-power holders. Just like the Indian government did 70 years ago, world-class architecture actively embraces accessibility, opening up previously closed spaces to the public.

Architects Lacaton and Vassal, 2021’s Pritzker Prize winners (considered the Nobel Prize of architecture) define good architecture as “being open to enhance the freedom of anyone. It should not be demonstrative or imposing, but it must be something familiar, useful and beautiful...“ Their award citation applauds their “democratic spirit” of architecture.

Similarly, the international design competition to extend the space of the European Parliament in 2020 asked not only for “the best working conditions” for parliamentarians in its design brief but significantly, for Parliament “to be open to citizens, to interact with them”, and to include public spaces for dialogue because “the Parliament of the Members is a Parliament of the People”.

Whether for imperial or democratic requirements, architecture stays contemporary by adapting, responding and being shaped by the requirements of the era it finds itself in.

Its second core value today is, therefore, an obvious response to our world’s greatest current concern – climate change. Sustainability is the other unmistakable paradigm shift in the world of architecture today.

Adaptive reuse is the term for it and every quality architectural firm in the world knows they cannot submit proposals that ignore this.

Unlike our demolished Netaji and Naoroji Nagars where between 14,000 and 17,000 trees were horrifically butchered and scores of houses levelled; Lacaton and Vassal’s award-winning project transformed an existing public housing block in France using their “never-demolish” principle, by careful extensions of space without demolition and reconstruction.

Their Pritzker citation says there is no opposition between architectural quality and environmental responsibility. Both can be achieved with sensitivity and thoughtfulness. The European Parliament competition brief too asks for its design to “set an example in its environmental approach” by prioritising sustainability.

Democracy and sustainability thus emerge as core values in every setting of excellence.

This confirms the gold standard of world-class architecture today as a people-centric vision. It regards people as its VIPs. Secondly, it will “respond to the climate emergencies of our times”, as the Pritzker citation puts it, and aim for a minimal carbon footprint – now a sacred non-negotiable anywhere in the world where sanctioning authorities actually work.

There is no question of wasteful constructions built at the cost of public space or insensitive, heavy carbon-belching projects that destroy greens and public space; getting go-aheads from municipal corporations – or awards. Both would be considered ignorant at best and regressive at worst.

How does Central Vista fare on these criteria?

How does the Central Vista, India’s biggest, most prestige-attached urban project in the last 50 years, stack up to these codes?

Going by the core values of democracy and sustainability established above, the distance between actual world-class architecture and the Central Vista reconstruction seems unbridgeable. Both are entirely missing in this project.

As the project promises to fulfill democratic aspirations, let's take democracy first.

The philosophy that underpins the Central Vista is power-centric rather than people-centric. Its key ideas have no place in the 21st century.

These are:

Extreme centralisation that every urban planner strains to avoid

Enclosure that disdains integration with the larger urban space around it

Elitist use of space reserved for the powerful in a democratic era of equality

Geographical working contiguity in a digital age

Public inaccessibility

These form a 19th century sore thumb sticking out in the field of international design. Yet they are the ones on display here!

Take the form of the fortress like Secretariat buildings that will house 50,000-odd bureaucrats as isolated islands with high boundary walls and restricted-access underground entry.

The old mingling of government and public/semi-public lands had a shared-access flow allowing bridges between citizens and their government. This was in keeping with the larger wisdom in the 1960s of freeing up this core space of mundane administrative activity and reserving it for the citizen who could walk in and out at free will.

As the new Secretariat buildings replace the old public buildings, they will shrink public access here because their functions will change overwhelmingly to “government use”. Citizens will now automatically stop coming to the area that becomes an exclusive government enclave.

“There is no larger urbanscape plan here that involves the citizen,” says architect Narayan Moorthy. “Public buildings the world over don’t have boundary walls, they have visual porosity. Buckingham Palace, Whitehall or the White House all have railings that allow you to see inside and also share the area. The Mall in Washington is lined with public buildings so the citizen always has a presence. You find other ways to keep security intact if you have to take away public space. But why do that in the first place?”

“So, what exactly is the 'New India' conjured up by this vision,” he asks? “A highly unintelligent set of inwardly focused, opaque buildings, shutting out the ‘New Indian’ citizen, if you please!”

Take the orientation of these buildings in which the power equation is inverted. The best parts are reserved for career bureaucrats. While 6,000-odd trees could be the final toll of Central Vista, led by the destruction of a “deemed forest” (2,000-odd trees in IGNCA alone, as Part Two will explain) there are a privileged few who will access the greenery snatched away from the citizens. This is the bureaucrat and politician who get the exclusive right to enjoy the greened courtyard inside the building. The citizen passing by will see only the high walls of massive mono-blocks.

Many of the current buildings are set deep inside, are three to five floors lower, and have ground level entries. They share their assets generously, allowing the greenery and skyline to be collectively enjoyed and fully available to the public. See pictures below.

These will now be shut off forever. See plan below.

Take the scale of these buildings. It is the very antithesis of world-class architecture’s core values that treat the citizen as the VIP. 4.58 lakh sqm will be physically demolished and 17.08 lakh sqm or four times more space built for the same number of employees! By any measure, international or domestic, this is a staggering overbuild at the expense of the citizen whose 100 acres of public use land was used for this extravagant purpose.

Defining ‘world class’ differently

Obviously “world class” here has a different meaning for this project.

PM Modi uses the terms “smart solutions” and “efficiency” interchangeably in the sense of technological capability and orderly interiors. This defines efficiency as the best systems and materials that money can buy.

The Secretariat buildings will therefore have the very best HVAC systems, sound systems, travelators, lounges, marvels like an underground rail and automated entry, the best marbles and granites, organised worker flow, hierarchy-wise office spaces, cafes and gyms for a dash of Silicon Valley, etc.

But superficial manifestations of the “latest” systems as “world class” cannot keep it world class if it opposes the very core values that define it – democracy and sustainability.

World class doesn’t mean creating vast, restricted-access bubbles of efficiency and order that work by cutting off the chaos of the citizenry outside to have order within. It means transforming an environment as a whole by improving the lives of the larger public, not just a privileged few. There is no point having World Class inside and Third World outside.

This project’s definition of “world class” therefore promises new-school but delivers the same old old-school. For example, it creates hi-tech digital systems but oddly, also enforces physical proximity with government functionaries literally sitting next to each other – in an age of Pegasus!

Surely the purpose of world-class technology is defeated if the government still works in this archaic manner of meeting physically in corridors and exchanging documents in red files? Surely then, it is their systems that need upgrading, not the buildings. These are simply no longer the exigencies of a 21st century working environment.

“The government has been decentralising as a conscious policy since 1961,” says Moorthy, “and so has the rest of the world – for good reason, because it’s the sensible thing to do! China and South Korea are moving government administration out of their capitals. We are the only people bringing government into the city centre!”

The concept of land efficiency

The answer to these contrarian trajectories could lie in the concept of land efficiency as articulated several times by chosen architect Patel who reveals a disturbingly developer type understanding of land as a “costly resource” that must be maximised – not as a public asset that must be protected for the greatest good for all.

He thus determines the appropriate amount of FAR built according to the value of the land – not by need or function.

“If you have land,” he says, “you will determine according to the price of land. This is costly land – I must use it to its potential. Or this is inexpensive land – I don’t need to build too much floor space on it.”

“When government decisions are taken,” he adds, “by and large, price of land is not taken into consideration so they end up not using that costly resource efficiently – and that’s essentially what had happened. This project is reversing that situation. Listen, land is precious! We must use it properly. That’s what this project is doing. Let's knock down the buildings that are using land inefficiently. In fact, land is so precious that it makes sense to knock down buildings and accept that cost and build on top more floor space.”

But can this define even the most precious heritage zone in the country? According to this definition, wouldn’t even India Gate then be land inefficient?

“In a constitutional democracy, assets are held in fiduciary trust because they deliver governance,” says architect Madhav Raman. “There is no question of evaluating government land because there is never any intention to sell! The same government can hold land in Central Vista and Dwarka. Does he mean to say government should not build in Dwarka but only in centralised areas of Delhi because the land value is higher? What’s the point of Central Vista being worth Rs 20,000 crore if you have to wade across slums and potholed roads and decrepit infrastructure to reach it?”

What if more floor space is not required? Why does costly land need to forcibly have more floor space especially if it has been designated for the public as IGNCA, National Museum, and National Archives had been? Why cannot it be enjoyed as it has always been classified – as public land for the public – for melas, leisure, culture or the beautiful 2,000-tree deemed forest within IGNCA?

Secondly, what about public land held in trust? The newly independent government in 1947, short of resources, housed certain ministries in World War Two barracks on public land temporarily. Patel refers to them as “inefficient” and “hotchpotch”. “You have all this land and tiny buildings...” he says, with evident disbelief.

Raman sharply disagrees.

“Historically after independence, the state has always emphasised utilitarian and frugal modernism. It never built more than what it specifically needed at any point in time. Because of Central Vista’s heritage value and its sanctity as a national space, architectural control has been a concern diligently asserted by government committees here in 1962, 1975 and 2009 [see picture] to reinforce the importance of the use of this space for the nation as a whole. Different architects designed different buildings here at different points in time.”

“So,” he says, “not hotchpotch – but care, diligence, frugality, diversity and gradualism.”

Public land is an asset held in the highest trust. No world class architect will wilfully undermine its sanctity as the very definition of world-class architecture today is profoundly democratic, not authoritarian. It is why the understanding that the barracks land would revert to its original “public” use once the ministries found a permanent location, has broadly held till now.

Yet a mindset that approaches the Central Vista like a complex that must deliver “efficiency” cannot envisage public land as sacred. There is absolutely no understanding of this notion of the government holding the land in fiduciary trust for the people – a highly ominous sign for those entrusted with transforming India’s national space.

It is why the regime believes its mandate for power gives it the right to breach this trust and divest citizens of 100 acres of their land. It is why it returns Central Vista to the same purpose it had during the Raj: to show the citizens where might and power lies.

On November 22, the Supreme Court agreed with the government’s view that the Central Vista Project is a matter of state policy and does not merit judicial intervention. It rejected a petition that argued for restitution of public land designated for recreational use.

This is part one of a four-part series.

Next: Part Two on How Central Vista stacks up to the world-class codes of sustainability.

NL Interview: Why a petitioner against Central Vista project became an advisor for it

NL Interview: Why a petitioner against Central Vista project became an advisor for it Central Vista: Why Modi’s New New Delhi isn't a shining city

Central Vista: Why Modi’s New New Delhi isn't a shining city