2021: The year the farmers went up against 'Godi' media, and won

And by doing so, the farmers reflected the general public’s lack of trust in mainstream media.

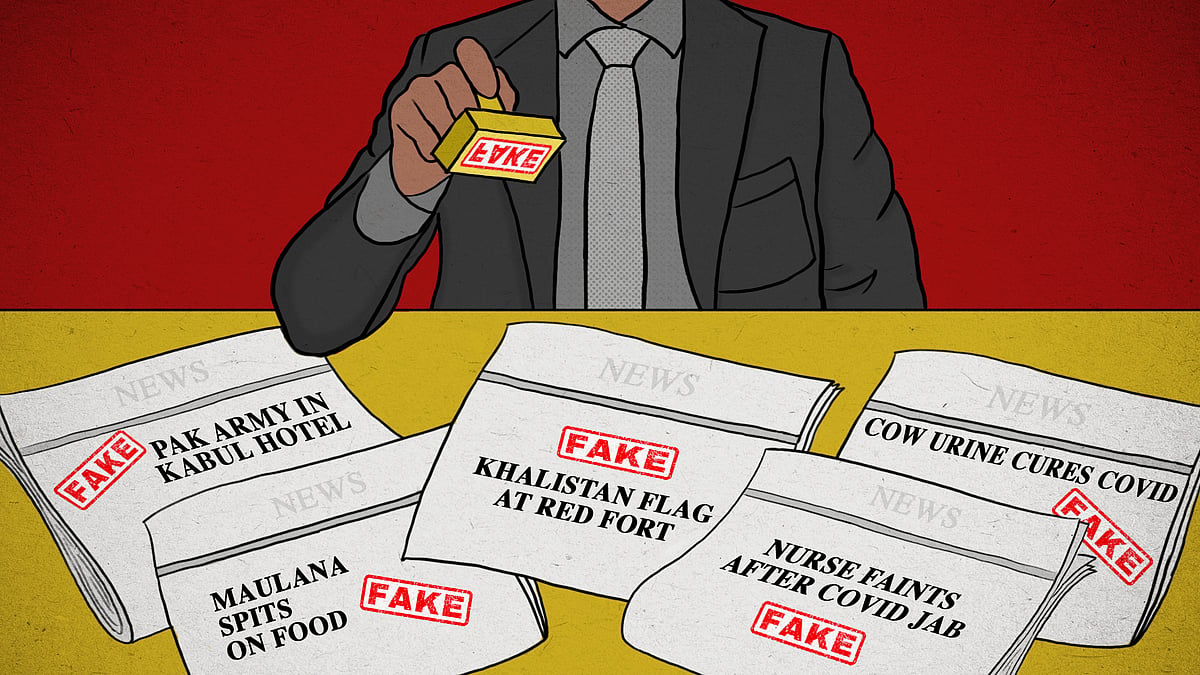

On January 26, 2021, a member of the farmers’ protest (which began after three contentious farm bills were passed into law) was seen hoisting a flag from the ramparts of the Red Fort in Delhi.

The incident was widely reported and most media depicted the protesting farmers as violent miscreants. Multiple news channels were quick to declare that the flag was “Khalistani”, building on the baseless allegation that there was a “Khalistani hand” puppeteering the protest.

“Our first priority was to clear this false claim,” said Harinder Happy.

Happy was one of the media coordinators at the farmers’ protest. At the time, internet had been cut off at the Delhi border. So, to get the word out about the flag being a Sikh emblem and not Khalistani, Happy had to walk four-odd kilometres to access data network. With the help of supporters who were outside Delhi and some outside the country, the protesters were able to get the facts out to the Indian public.

Soon enough, corrections started appearing on social media, with users pointing out that the flag on the Red Fort was the Nishaan Sahib, the triangular flag that can be seen atop every gurudwara.

In the fight against misinformation, the farmers had scored a small win.

For the duration of the farmers’ protest – from November 26, 2020 till December 11, 2021 – the resistance was as much to the government that wanted to impose the farm laws as the mainstream, or “Godi”, media that was seen as an agent of prime minister Narendra Modi’s government.

The protesting farmers complained of being vilified by mainstream news media and attempted to counter this by setting up a well-organised media strategy. Journalists had to navigate the hostility of the people at the protest site as well as the challenges posed by news channels (sometimes their own) that deliberately misrepresented the farmers’ movement.

A media strategy

Ashutosh Mishra, a member of Samyukt Kisan Morcha’s media team and media coordinator of the All Indian Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, remembers that when the protests first started in Punjab, there was no interest shown by the national media.

“It was only after November 26, 2020, when the farmers reached the borders of the capital, that the Delhi media attended a press conference by the farmers,” Mishra said.

As the media reports started to come in – many of which felt inadequate or prejudiced to the protesters – it became clear that the farmers needed to set up a system by which accurate information could be shared. For the thousands of protesters, the bi-weekly newsletter Trolley Times was set up and its first edition went out on December 18, 2020. The four-page publication had updates from the various protest sites and human-interest stories from the protesting farmers.

For the media, daily press releases were written up in Hindi, English and Punjabi by media coordinators like Happy. Mishra said each press release was approved by a nine-member core committee of farmer leaders, so that perspectives of the different factions of the protest were kept in consideration. WhatsApp media groups were set up with reporters from print, television and digital media, and updates would be sent to those groups. There was a separate email list for Punjabi media. A social media team, which had a fluctuating strength of members, was set up since Twitter trends often end up becoming primetime news.

Happy, who is a PhD scholar in agrarian studies from Rajasthan’s Sri Ganganagar, said that the main reason for the media coordination teams was that the protesters felt they were being misrepresented.

“We could not take that there were inflammatory narratives in the media [about the protest], such as Khalistan, despite real human stories unfolding at the protest in front of us,” he said.

It seemed clear to the protesters that there was a certain kind of story that mainstream news channels wanted to tell.

“They [the reporters] would target one person who does not know enough and would end up saying something extreme, and the news channel would then play that to brand the protest,” said Mishra.

“We spoke to every media house equally. Some showed the truth and some showed what they wanted to,” said Bharat Kisan Union leader Rakesh Tikait, who became the most prominent face of the farmers’ protest.

The challenges of reporting

Reporters said they could feel a change in the way the farmers treated the media within a few days of visiting the protest sites.

“The first few days went smoothly, but after five to 10 days, it became difficult to even enter the protest site,” said a reporter with Arnab Goswami’s Republic Media Network, on condition of anonymity.

Routine reporting from the protest sites became difficult. “We were often heckled and some of our colleagues were even held up by some protesters. After a point we started going without our identity cards and channel mics,” said the reporter, adding that at one point, the police asked the journalist to report from outside the site “for our safety”.

In sharp contrast, for Ravish Ranjan Shukla from NDTV, the time spent at the protest sites was a “great reporting experience”.

“A lot of the Delhi media is so used to speaking with powerful and high-profile individuals that they often tend to trivialise the farmer,” he said. “The key was to go there with a sensitivity and no preconceived notion about the farmer.”

Shukla said those who reported without preconceived notions “were able to build a trust” with the protesters. “I saw how some farmers had a refined political sense and worldview that one can’t even compare to a politician,” he said.

The Republic reporter said that for all the hostility, there were always some “friendly faces” at the protest. “What was strange was that the farmer leaders would always talk to us, regardless of the channel, but some people on the ground categorically decided not to,” said the reporter.

That, in fact, was part of the protesters’ media strategy. To ensure a unified stand is presented, those working on the media strategy figured out which farmer leader would appear on which channel, depending on its viewer base.

Speaking about those who were angry at certain reporters for having misrepresented the movement, Mishra said, “We made sure to tell them that they can choose not to give a bite to certain channels, but getting into scuffles was not an option.”

However, reporter Hiten Vithalani from Zee Hindustan alleged he was “held forcefully and beaten up” while his cameraperson was “kidnapped” by protesters some time after January 26, 2021, when the two of them tried to report that the protest sites were emptying out (the protest continued till December 11, 2021).

“The farmers sent fake messages from my phone to my cameraman and then held a press conference presenting me as a reporter of the Godi media,” Vithalani said. “They did this to malign my channel.”

Vithalani admitted reporting became difficult for him after Zee News’s Sudhir Chaudhary claimed the separatist Khalistan movement had “infiltrated” the protest. While Vithalani believes the protesters were brainwashed into distrusting mainstream media, he also believes the protest had “Khalistani elements and extreme communists”.

A semblance of truth

Leaders of the farmers’ protest have pointed out that despite repeatedly being misrepresented, they continued to speak to mainstream media. “We spoke to almost every reporter who came, without being selective, because it was never the news reporter who was wrong. It depended on what their media house reported,” said Tikait.

Journalists on the ground saw reports being twisted out of shape. “What I learnt was that if as a reporter, you make sure you say what was happening on the ground when you’re going live, then despite the anchors in the studio choosing what they want, it creates a semblance of truth and builds trust with people on the ground,” said a reporter with the India Today group, on condition of anonymity.

Shukla said, “I remember an instance when a reporter from a news channel spent hours gathering footage on the day when farmers were leaving the protest site. He wanted to show that their year-long struggle and determination had finally culminated in a positive outcome, but instead of showing this, his channel ran the footage with the headline ‘a year of aiyashi [debauchery]’.” Shukla declined to name the channel.

Some channels would also send a “preset brief” to reporters, like instructions to show dwindling numbers at certain protest sites and other kinds of selective reporting, said Shukla. This would often make it difficult for the on-ground reporters because the farmers mistrusted the networks that the reporters represented.

A reporter with the India Today group found their way around this problem.

“Going on the ground so many times meant that people started to know you on a personal level. So, even after the network that I represented or if my anchor said something on air that the protesters didn’t like, they would never be rude to us. Of course, there were people at the protest who were always upset with us because of their scepticism of the media, but there was always a way to reason it out,” said the reporter on condition of anonymity.

Unlike Vithalani, the reporter from the India Today group found the protesting farmers to be helpful.

“I remember tear gas shelling was happening when the farmers first reached the Singhu border. A group of farmers rescued my colleague and me,” said the reporter. “Despite the different ways in which the protest was projected on news channels, the situation on the ground was unlike anything we had seen before, especially for reporters like me from the younger generation.”

On the final day of the protest, before going home, the farmers thanked all the reporters who were present, regardless of the channel they represented. Shukla remembers the moment as a poignant and touching one. “They said they have forgiven everyone, even the media that called them names,” said Shukla, adding that this gesture spoke volumes about the maturity of the movement.

Vithalani saw it differently. “On the last day of the protest, they [the farmers] had this realisation that they would have been sitting here for ages if the national media had not covered their protest,” he said. “If the media decided to boycott them because they were beating up reporters, the protesters would still be sitting here today.”

Broken trust

Mirrored in the farmers’ ambivalent relationship with the media is the Indian public’s attitude towards news channels and publications. There was an unprecedented collapse of faith arising out of coverage that vilified the protesters and trivialised their concerns. Most popular news channels towed the government’s line, as they have in the past with issues like demonetisation or the Centre’s handling of the Covid pandemic. However, this time the audiences were not persuaded. Mainstream news repeatedly told viewers that the protesting farmers were misguided, violent and anti-national, but public sympathy remained with the protesters.

“The camera and pen are already being held at gunpoint in the country. We support the freedom of press, so we spoke to everyone,” he said. “Those who lost a good public image were the media houses who showed misleading narratives about the movement,” said Tikait. “It is going to be a long-drawn task for them to get the trust of the public back.”

A dupe of a year: How a section of Big Media conned readers with advertorials

A dupe of a year: How a section of Big Media conned readers with advertorials Misinformation on vaccines, farmers and minorities: India’s fact-checkers had a busy 2021

Misinformation on vaccines, farmers and minorities: India’s fact-checkers had a busy 2021NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.