What does Amarinder Singh’s exit and Charanjit Singh Channi’s elevation mean for Congress in 2022?

The party is putting its best foot forward ahead of the assembly election, though Navjot Singh Sidhu may emerge as the new captain.

“Masterstroke”, “Chanakya reincarnate”: this is what anchors of Noida-based news channels routinely yell at the top of their voices when the Bharatiya Janata Party effects a desperate change of face or breaks an opposition government in any state.

However, when it came to political masterstrokes, the transition in Congress-governed Punjab from Captain Amarinder Singh to the low-profile Charanjit Singh Channi, the border state’s first Dalit chief minister, is as good as any. True, it came after a six-month power tussle between the erstwhile Patiala maharajah and challenger Navjot Singh Sidhu but, despite all the hiccups, the Congress looks in pole position ahead of the election early next year.

Curiously, apart from the primetime anchors, even the Delhi commentariat was crying hoarse this time around at the turn of events, which saw a “humiliated” captain tendering his resignation and a back and forth between Chandigarh and Delhi at the end of which the Congress pulled a rabbit out of a hat, in Channi. It isn’t just the symbolism of it – the transfer of power from the erstwhile maharajah now occupying the seat of power as a people’s representative to a Dalit, whose community makes up a third of the state’s total population – but the Congress has also punctured the opposition parties’ collective election pitch to propel a Dalit to a key position as chief ministry or deputy, killing two birds with one stone.

Why Amarinder Singh was eased out

Contrary to popular perception outside of Punjab, the Amarinder Singh government had become very unpopular in the state in recent times, with the captain seemingly banking on the farmers’ protests against the agricultural reform laws enacted by the centre to see him through. It also needs to be recalled here that Singh had announced that the previous election would be his last, before belatedly having a change of heart.

While Sidhu became the face of the opposition to the captain, he found increasing support among Congress legislators only because they read the writing on the wall. The fact that many manifesto promises of the party from 2017 remained unfulfilled, and the captain being in no apparent hurry to implement them even after prodding by the Congress high command, forced them to join forces with Sidhu. Of late, the captain had been running the state sitting in a farmhouse on the outskirts of Chandigarh, relying on a set of bureaucrats to run the administration on his behalf, abandoning the civil secretariat and losing his touch with people in the process. Sidhu merely personified the larger revolt from within the party against the captain rather than engineering it personally. In fact, the likes of Channi and deputy chief minister Sukhjinder Singh Randhawa had been voicing their dissent even before Sidhu anchored it to become the Pradesh Congress Committee chief last month.

Perhaps Amarinder Singh had assumed that the high command couldn’t risk replacing him so close to the poll, which emboldened him to defy the leadership. But, with surveys already making it apparent to the Gandhis that the party could lose on account of anti-incumbency and a resurgent Aam Aadmi Party close on its heels, the leadership rallied behind Sidhu, thus paving the way for a change of face.

Amarinder Singh had the option of bowing out in style, and devoting his time to writing books on India’s military history, as he had claimed in interviews in the lead-up to the previous poll, but his personality clash with Sidhu ensured that he wouldn’t throw in the towel.

It wasn’t just anti-incumbency and the lack of accessibility which proved to be the captain’s undoing but the Punjab and Haryana High Court’s April order quashing an SIT report on the Kotkapura firing incident in 2015 – an emotive issue which determined the fate of the Shiromani Akali Dal-BJP government in 2017 – turned the tide against him. That verdict gave disgruntled Congress leaders an issue on which they could target the captain. There have been many references to Amarinder Singh’s alleged soft approach towards the Badals and his failure to bring the perpetrators of the desecration of the Guru Granth Sahib to justice. Sidhu’s elevation as PCC chief hastened the process, forcing Singh to quit after finding himself repeatedly undermined.

The resignation of Amarinder Singh happened quicker than the high command anticipated which meant they had to swiftly come up with a replacement. That someone like an Ambika Soni, just a year younger than Amarinder Singh and whose politics has been concentrated in Delhi for most of her career, was looked upon as a probable replacement makes it apparent that the leadership was essentially groping in the dark, before finally zeroing in on Channi. In fact, Sukhjinder Singh Randhawa was almost named chief minister before Channi’s emergence.

Sidhu: Kingmaker or king?

In a 1996 interview, 13 years into his India debut and after reinventing himself as an agile fielder and earning the moniker “Jonty Singh”, Sidhu had let it be known how much he wished to lead the Indian cricket team. Unfortunately, he never got a chance to lead India before his retirement in 1999. With Captain Amarinder Singh out of the way and Channi more of a “night watchman”, Sidhu has the chance to emerge as Punjab’s new captain post elections.

But Sidhu has always been a bit of a maverick and it would depend on how he plays the game of politics from now on. Nothing is cast in stone; nonetheless, being PCC chief ensures that Sidhu has a crucial say in candidate selection which would be key when heads are counted in a winning scenario. But with Amarinder Singh letting it be known that he would not let Sidhu come anywhere close to chief ministership, even the possibility of the captain himself taking on Sidhu cannot be ruled out at this stage.

Amarinder Singh’s future

The captain’s next move is keenly anticipated and it is anybody’s guess at the moment. His statements post resignation indicate that he is not averse to tying up with the BJP in some form as the election approaches. However, the BJP’s prospects in the state are looking grim following the enactment of the farm laws. Whether Singh dramatically ties up with the saffron party with a strong national security pitch by dubbing Sidhu “anti-national” remains to be seen but even in such a scenario, it may not really work as there is hardly any time left for such political realignments. It is also unclear how many prominent Congress leaders would quit and join the captain if he were to split the party and whether all his supporters would be amenable to tying up with the BJP.

Singh going with the SAD or AAP is even less of a possibility, although nothing can be ruled out in politics. It is also possible that Singh would remain in the Congress for the time being, daring the high command to throw him out or sabotage the party’s prospects from within.

How the poll is stacked up

While the Congress has definitely improved its chances with this change of guard, AAP has emerged as its principal challenger. Primarily drawing its strength from the Malwa region, AAP has also managed to make inroads in rural areas and among sections of Dalits, thus improving its prospects from 2017 when it was tipped to do well but ended up a distant second. Sukhpal Singh Khaira, the AAP’s former leader of the opposition, recently joined the Congress but the AAP still has popular leaders like Bhagwant Mann. Lacking pan-Punjab appeal and organisational muscle is a cause of concern, though.

The Shiromani Akali Dal looks down and out for the moment but it has a robust organisation and also a fresh partner in the Bahujan Samaj Party after breaking off its two and a half decade alliance with the BJP over the enactment of the farm laws. The BSP has been steadily losing ground in Punjab after an impressive debut in the 1992 election when it won nine seats; yet an alliance with the SAD could reverse that if the two parties can transfer their votes to each other with the state’s one-third Dalit vote being critical. Also, the previous time the SAD and BSP came together in 1996, both parties had benefited, sweeping 11 of the 13 Lok Sabha seats. But for the parting of ways shortly thereafter, ostensibly on account of the BSP’s pre-poll alliance with the Congress in Uttar Pradesh (the actual reason was Parkash Singh Badal’s mission to scuttle senior colleague Surjit Singh Barnala’s chances of becoming the third front’s consensus prime minister), the BSP would have most likely emerged as a major political force in the state.

In the event of Amarinder Singh splitting the Congress and floating a splinter outfit to ally with the BJP, the latter would try to mobilise support among the 39 percent Hindu electorate by campaigning extensively on national security. As of now, the Congress is the party of the Hindus in Punjab and, more than anything else, it is the core Hindu vote that propelled the Congress to a huge majority in 2017, with their unease at the AAP for its dalliance with radical Sikh elements. That would also be a lesson for Sidhu to not make an appeal to the hardline sections of the Sikh community lest the party alienate the moderates and the Hindu constituency in the polls. Punjab’s turbulent political history, despite the relative peace prevalent today, will be an important factor for all political parties to take into account.

Congress prospects

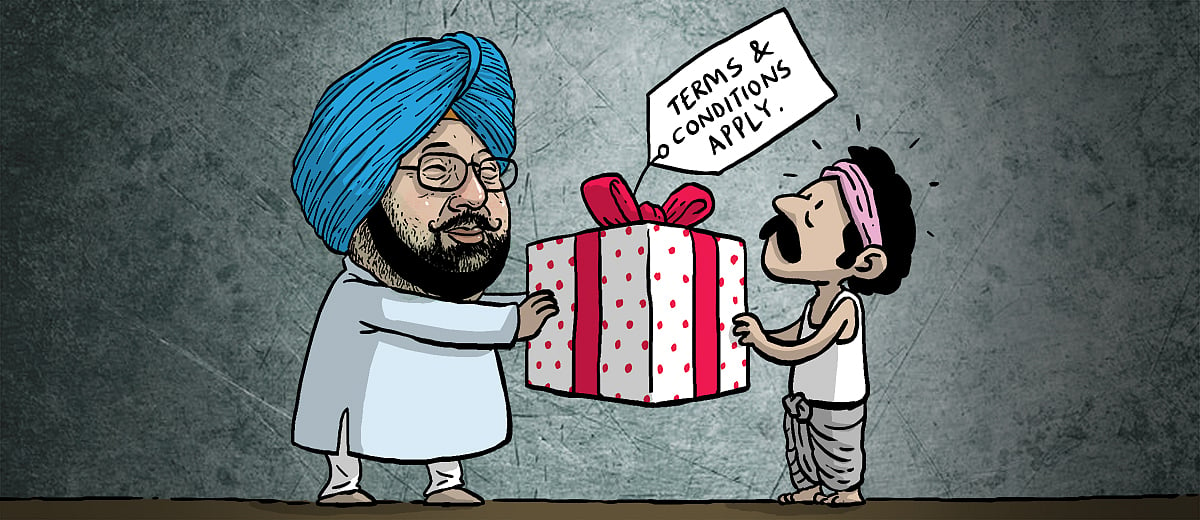

As for the Congress, despite putting its best foot forward, chief minister Channi will have to hit the ground running in the next 100 days and implement as many pending manifesto promises from 2017 as possible. The Congress would also need to keep the electorate guessing as to who would be chief minister if it were to retain power so as to draw votes from both the numerically strong Dalits and the Jat Sikhs, who form another formidable bloc.

A remark by Harish Rawat, the All India Congress Committee’s general secretary in charge, that the party would go into the election under the leadership of Sidhu queered the pitch and, despite issuing a clarification, it nearly negated the raison d'etre of Channi’s elevation, as former PCC chief Sunil Jakhar tweeted. In Channi, the party has an aspirational face who overcame many obstacles to reach the top, which should resonate with a section of the electorate.

The election results will ultimately determine whether the decision to ease out Amarinder Singh was the right call to make. But if the party were to go to poll with the captain at the helm, it may not fare any better going by the sentiment on the ground. The Congress high command needs to be commended for shedding its status quoist approach despite the accidental nature of Channi’s elevation and for sticking through with their decisions just this once.

Why Sidhu’s elevation as Punjab chief is rooted in Congress’s Delhi darbar culture

Why Sidhu’s elevation as Punjab chief is rooted in Congress’s Delhi darbar culture Amarinder farm loan waiver has a lot of holes but media won’t dwell on it

Amarinder farm loan waiver has a lot of holes but media won’t dwell on itNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.