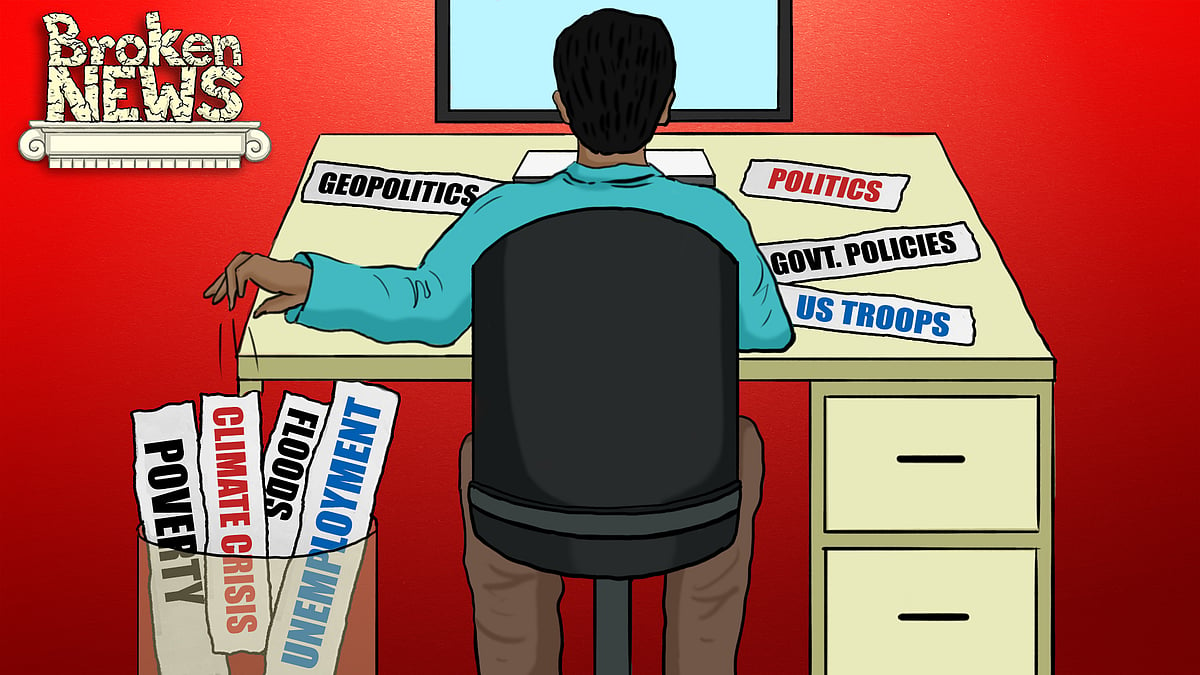

Apart from Russia-Ukraine and assembly polls, here are other news stories we must not forget

The fog of war must not detract from the urgency of press freedom issues in Kashmir and climate change worries across the country.

Just as we were getting over the war against a virus, the world, or at least Europe, has been plunged into another war. And the repercussions are being felt everywhere.

But amidst the fog of war following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that understandably dominates the news everywhere, including in India, and even as the cacophony of the assembly elections in five states subsides, there are some other stories that must be noted, reported and not permitted to be overwhelmed by the immediate.

In January, I had written about what the sudden closure of the Kashmir Press Club meant to the already beleaguered journalists working out of Kashmir. At that point, only Sajad Gul, who was a trainee journalist with Kashmir Walla, had been arrested. The digital platform's editor, Fahad Shah, was still free. Today, both these journalists are in jail.

Both of them were first called in for what appeared to be routine questioning. When they went to the police station, they were arrested in one case. As soon as they got bail, they were immediately rearrested in another case.

The pattern was identical, the charges frivolous. But the laws under which they have been detained – the Public Safety Act in the case of Gul and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act in Shah's case – are anything but frivolous. They ensure that the chances of their being released on bail are practically non-existent.

Since Shah's arrest on February 4, it has become evident that there is a clear method to this madness in Kashmir, as this story in Newslaundry outlines. It is to intimidate, threaten and control any and all journalists who want to do their jobs – which is to report as accurately and truthfully as they can about what is going on in their state. Their passport to safety is compliance. Stick to the government narrative and terminology and you will remain untouched. Stray from it and you risk not just the routine interrogation and surveillance but the virtual certainty of a jail term.

All this is happening despite the ruling by the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in 2021, quashing the FIR against another journalist Asif Naik, which stated: “No fetters can be placed on the freedom of press by registering the FIR against a reporter who was performing his professional duty by publishing a news item on the basis of information obtained by him from an identifiable source.”

Gul and Shah were doing textbook journalism, reporting all sides of a story. For giving voice to people who questioned the official narrative, they have been charged with “glorifying” terrorism.

It is therefore not surprising that at least nine journalists, who write for media houses in India and abroad, have quietly left the state last month. One of them, senior journalist and author Gowhar Geelani, was summoned to a Shopian court on the charge of having tweeted a story that appeared in Kashmir Observer about an encounter between militants and the police in Shopian district. It's a short story, a few paragraphs long, that states that a policeman was injured in the clash. For not appearing in court in this case, Geelani has been declared an absconder and there is a warrant out for his arrest.

None of these journalists can risk returning to their state even though being there is essential to their existence as journalists. Given what has happened to two of their colleagues, they have little confidence that they will be spared.

Routine journalism is being criminalised in Kashmir, as this story in Article 14 documents. Note that the story has no byline. That too is a fallout of the oppressive reality in Kashmir where journalists reporting on human rights issues are being compelled to write anonymously for fear of retribution by the authorities.

What is happening currently in Kashmir is a direct attack on press freedom, on the right of journalists to do their jobs, to earn their livelihood, and to report without fear or favour. If you remove that right from them, you are killing journalism. You are strangling the free press. And if you can do that in Kashmir, and get away with it because the rest of the country is too absorbed in other issues, then the experiment will be repeated elsewhere in this country. Make no mistake about that.

One of the journalists who has been compelled to leave his home state asks these questions:

“What is our crime? That we report facts on the ground? That we refuse to become mouthpieces of the administration? That we do not act as their extension arm and stenographers? What is the fault of our family members? Why are they being harassed for our professional work? Most journalists have been silenced in Kashmir. This enforced silence is aimed at killing and distorting the Kashmir story and to manufacture a false ‘all is well’ narrative.”

So, even as we wring our hands over Ukraine, as we discuss what India should and should not do, and watch videos of helpless Indian students stuck there, spare a thought for the death of journalism in Kashmir.

There is another kind of journalism in India that needs an urgent injection of investment if it is to survive, and that is environmental journalism.

Last week, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its latest report. What it says about India is particularly alarming.

Sea-level rise and cyclones, a direct consequence of climate change, threaten not just major coastal cities like Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata and Visakhapatnam but also smaller coastal towns in Goa and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Furthermore, unplanned urbanisation in the Himalayas is a cause for concern. People living in these towns will face more frequent landslides and flooding, given increasing rainfall and melting glaciers that are already leading to flash floods.

All these concerns need to be explored by the media with stories from these regions so that the challenges posed by global warming translate into what is already happening on the ground.

There is also an urgent need for stories that look at infrastructure projects, already in the pipeline in many of the cities identified in the report, that make little environmental sense in the light of the inevitability of climate change impacts.

The multi-crore coastal road being built in Mumbai, for instance, that will benefit a tiny percentage of car users in a city where the majority use public transport, is a case in point.

Another is the Char Dham project in Uttarakhand. Despite the recommendations of the expert panel set up by the Supreme Court, and the recent resignation of its chair, Ravi Chopra, the government is hell-bent on going ahead with it.

However, except for sporadic reporting, usually triggered by protests by people adversely affected by such projects, such as the fishing community in the case of the coastal road, there is hardly any effective environmental reporting in mainstream media. One has to turn to specialist digital platforms like Mongabay, the Third Pole or the Centre for Science and Environment for such reports.

Environmental reporting cannot be done sitting in an office. Journalists need the time to investigate, to travel, to understand all aspects of the story so that they can report in a way that will have an impact on policy-making while at the same time informing the public. This is an investment the mainstream media in India, barring some exceptions, appears unwilling to make.

'Reporting is public service, not crime': 58 organisations write to J&K LG on Fahad Shah's arrest

'Reporting is public service, not crime': 58 organisations write to J&K LG on Fahad Shah's arrest From climate change to healthcare: Why is there no space for these issues in Big Media?

From climate change to healthcare: Why is there no space for these issues in Big Media?NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.