Sarpatta Parambarai: Pa Ranjith continues his quest to smash stereotypes

There have been multiple movies about boxing, but Sarpatta is in a league of its own.

Writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie once said that the problem with stereotypes is “not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

For decades, Savarna movie producers have largely used mundane, type-cast protagonists, so much so that their repetitive stories have been the only stories thrust upon their largely diverse mass audience.

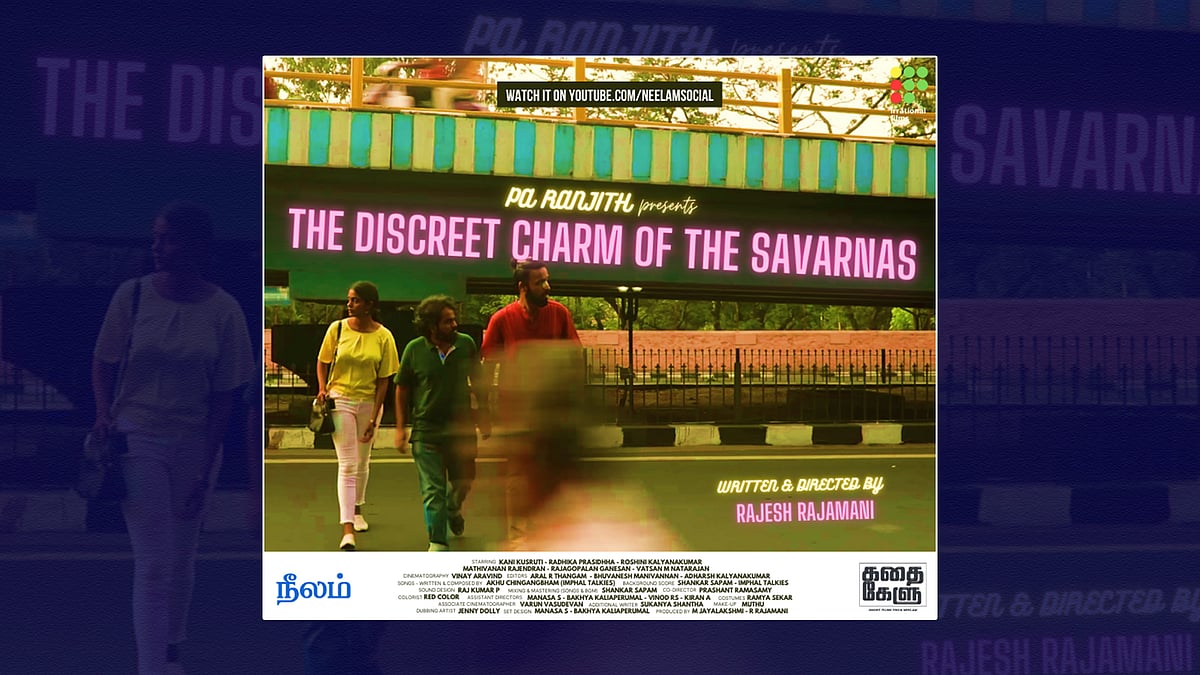

The Discreet Charm of the Savarnas: Rajesh Rajamani shows an unflattering mirror to upper caste filmmakers

The Discreet Charm of the Savarnas: Rajesh Rajamani shows an unflattering mirror to upper caste filmmakers  Why Bhumi Pednekar’s blackface in ‘Bala’ perpetuates the hegemony of colour

Why Bhumi Pednekar’s blackface in ‘Bala’ perpetuates the hegemony of colour The Savarna saviour complex isn’t the main problem with Article 15

The Savarna saviour complex isn’t the main problem with Article 15But director Pa Ranjith, well known for smashing movie stereotypes, brilliantly tells the story of boxing in his unique way in his latest movie, Sarpatta Parambarai, released on Amazon Prime Video last week. Ranjith shatters stereotypes not just by showing Dalit characters or portraits of Ambedkar, Buddha and Periyar in his films. He does it through dexterous film detailing, engaging storytelling, and writing unforgettable characters.

While choosing boxing – a theme used in dozens in movies – as the focus of Sarpatta Parambarai, Ranjith built a period drama set in the 1960s and ‘70s showing a bloody battle between two clans from north Madras, where boxing was an extremely popular sport among the working class and marginalised communities.

Kabilan, played by actor Arya, of the Sarpatta clan, is a Dalit working as a porter in a factory. He reluctantly stays away from boxing due to his mother, who believes his father’s boxing career had indirectly led to his death. But that doesn’t deter Kabilan from secretly practising and watching all the matches and deeply admiring Sarpatta coach Rangan (played by Pasupathy), who is also a local political leader.

A combination of circumstances and Rangan give Kabilan the opportunity to get into the ring to avenge a string of defeats at the hands of a rival boxing team. A low-class Dalit porter chosen for a key match ahead of higher-caste players means that Kabilan has to face wrath of his own clansmen, including Rangan’s family.

When he’s on the brink of a victory, sociopolitical forces come in the way and Kabilan is left to languish, this time to fight himself. This is an extremely crucial phase of the movie that sends a message to the downtrodden to rise like a Phoenix from the ashes. This self-realisation, which Ranjith calls “enlighten yourself”, comes from Buddha’s teaching of “atta deep bhav” (be your own light) and is reiterated in one of the film’s songs, Neeye Oli.

As the lyrics go, “Neeye oli nee than valiOyathini odambe, neeye thadai neeye vidai. Soodakkiddu narambe.” You are the light, you are the way. You are the hurdle, you are the solution.

While 2018’s Kaala, Ranjith had Ambedkar’s “agitate and organise” as a central theme while shattering the caste and colour paradigm. In Sarpatta, the focus is on Buddha’s message. Caste plays a role but it isn’t the central theme.

When the movie released last week, a still from the movie was widely shared on social media, showing Kabilan being encouraged by his Dalit friend, with a backdrop of Ambedkar on the city wall. "This is our chance," make your enemy tremble in fear." Kabilan represents all those who were never given an opportunity .

In another scene, when Kabilan’s men are trying to mediate with his own Sarpatta clansman Thanigai, who is out to kill Kabilan, Thanigai (Muthukumar) says, “Not long ago, you guys used to beg us for food.” But, he continued, he was willing to “forgive” Kabilan if the latter “cleans his house and clears the dead carcasses”. This humiliation further motivates Kabilan and his men.

What makes the three-hour movie outstanding isn’t just the realism with which it depicts its time period, or that the fights look real. It’s the fact that it knocks down stereotypes of typical boxing movies. Kabilan’s boxing fight is for the empowerment of the entire community, not just his family,if not his clan. But in the process Kabilan overcomes hurdles created by his own mind first.

It also transcends your typical movie with its cast of characters, including Kevin (John Vijay), Dancing Rose (Shabeer Kallarakkal), Mariamma (Dushara Vijayan) and, of course, Coach Rangan (Pasupathy).

One might theorise that it’s the plot of Sarpatta that makes it work. But without director Ranjith and without its social context and theme of self-empowerment, the movie would lose its soul. It would have then been yet another predictable boxing film, enjoyable enough but fleeting in memory.

One only needs to log onto Prime Video to compare Sarpatta with Toofan, a Hindi boxing movie released almost at the same time. In Toofan, for instance, Ajju Bhai (Farhan Akhtar) lives the life of a gangster in a slum to become a boxer because a woman tells him that boxing has “respect”. Both movies might be about underdog boxers but Toofan sticks to what is “filmy”, just like the name of the movie might suggest. The Bollywood clichés continue with Ajju Bhai’s coach being none other than his girlfriend’s father – played by Paresh Rawal – who is an upper caste who hates Muslims. But there is a justification tucked in for that too: his wife had died in a bomb blast. Rawal is the Savarna saviour who liberates the orphaned Muslim protagonist, Akhtar, who says his pain is “nothing compared to his girlfriend who lost her mother in a bomb blast”.

Yes, Ranjith shows Dalit characters in his movie, but the difference is that his characters do not look for Savarna saviours. They are assertive about community rights and are not meek. They carry Ambedkar’s message in subtle ways, inspiring entire communities. But these are peripheral messages; central to Pa Ranjith’s work is impeccable movie-making with magnificent consistency.

That’s why scenes like Kabilan going for his final match wearing a dark blue robe – indicating what it means for his Dalit community to see one of their own being represented on the big stage – have immense impact.

Pa Ranjith often maintains that his movies are a continuation of one another. In Ranjith’s first movie Attakathi (2012), a young college student, dumped by his lover and heading towards a moment of self-realisation, runs past a wall carrying a painting of Ambedkar. That moment signals change in his life. In Sarpatta Parambarai, newly-weds Kabilan and Mariamma are presented with portraits of Ambedkar and Buddha as wedding gifts. Both scenes show Ranjith’s thinking and ideas, and their continuation across different projects.

And with only five movies as director under his belt so far – Attakathi, Madras, Kaala, Kabali and Sarpatta Parambarai – Ranjith has already punched multiple stereotypes in Indian cinema. His next project, Natchathiram Nagarkirathu, is likely to keep this going.