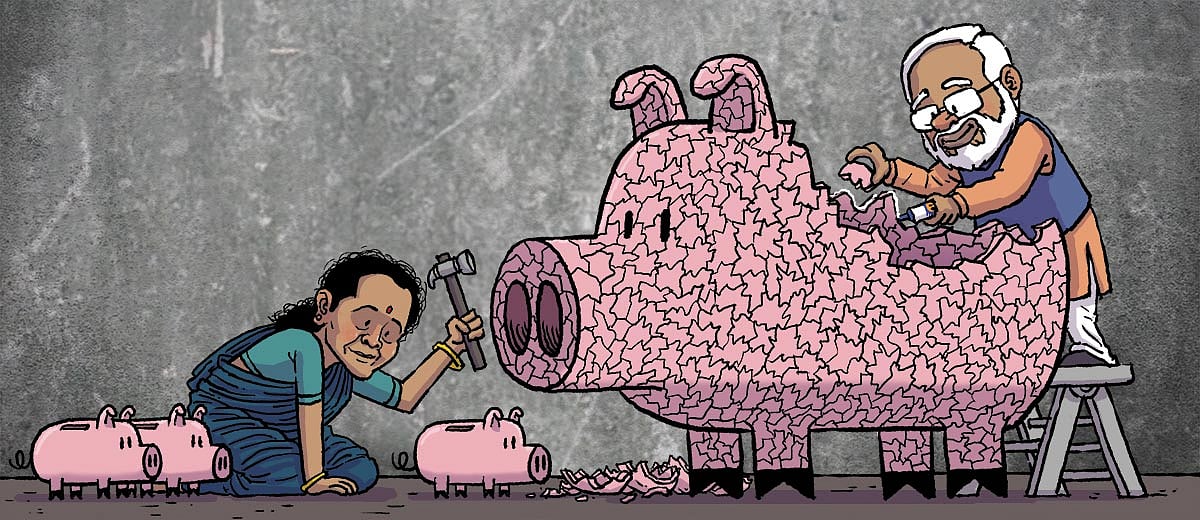

Cash transfer schemes in India: Bandwagon politics or smart economics?

They have been economically proven to work and, if executed properly, can work miracles.

The author was formerly an associate fellow with the AAP government.

On Sunday, Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal announced cash assistance of Rs 1,000 for every woman above 18 years of age if the Aam Aadmi Party is voted to power in Goa. The assembly election in the state, scheduled to take place next year, is expected to be a tripartite contest, with some even speculating a two-way fight between the AAP and the Bharatiya Janata Party.

Last month, the AAP grabbed eyeballs when Kejriwal made a similar announcement on cash transfers for Punjab, which also votes early next year and is expected to see an intense contest between the Congress and the AAP.

The AAP has kept governance and social welfare as its key electoral narrative over the years, promising key reforms in health, education, water, electricity, and women empowerment. However, the most interesting aspect of its governance has been the subsidies, or the so-called “freebies”, it has provided in water, electricity, and public transport for women. In Delhi, 20,000 litres of water for every household, electricity consumption upto 200 units, and travel in all public transport for women is free.

While these policies are contested with the argument that it makes people lazier (though this is debunked by studies) and leads to wastage, they have remained quite popular with the general public, reflected in the electoral support which the party has been able to garner over all these years.

As the party looks to expand its base, it went a step further this time, promising direct cash transfers for women. The scheme is expected to cost Rs 8,000 crore of the exchequer’s money in Punjab (similar calculations for Goa are ongoing) and will benefit about 1Cr women.

The concept of cash transfers is not novel. In fact, it’s gained significant popularity across the world. The idea of universal basic income has managed to move from being merely a topic of academic debate to being actually realised on the ground. As the Covid pandemic struck the world, multiple governments resorted to cash transfers, from advanced economies like the US and Japan to emerging countries like Pakistan and Namibia. In India too, several state governments, including Delhi, provided cash relief to a significant part of their population during the pandemic.

Small-scale cash transfer programmes have been running across Indian states for years. Old age and widow pension schemes, albeit small in amount, have proven to be quite effective. Recently, the central government started providing direct cash transfers of Rs 6,000 per year to over 12 crore farmers under the PM-Kisan scheme.

So, are cash transfers merely a populist political agenda? Or do they have larger economic and social ramifications?

Let’s take a look at how cash transfers fare as a social welfare policy.

Assume a market with a simple demand and supply graph (see below). For any product, the demand graph is usually downward sloping and the supply graph is upward sloping.

In a perfect competition, the equilibrium would be at price P0 and quantity Q0. However, with the introduction of subsidy = s by the government, the equilibrium effectively shifts to quantity Q.

Now, this has two or three implications.

First, a subsidy enables consumers with lower willingness to pay (the Q0 to Q crowd) to enter the market. However, consumers with even lower willingness (the poorest of the poor, i.e. the Q to Q1 crowd), who are often the main targets of these welfare policies, still end up missing out. In simple terms, until the cost for every consumer is 0, subsidies do not reach the neediest. But making cost 0 is essentially giving it out for free!

Second, by introducing a subsidy in the market, the government effectively creates a deadweight loss in the society. To think of it in simple terms, the market has been distorted, which creates inefficiency in the market (effectively, you are bringing in consumers whose willingness to pay is less than the equilibrium price and suppliers whose marginal cost is greater than the equilibrium price which brings in the inefficiency).

Third, the subsidy doesn’t go only to the consumers: the producers benefit as well (look at the additional producer surplus created). The consumers are paying the consumer price Pc, but the suppliers are getting the producer price Ps. In other words, by the very nature of this graph, a part of subsidy goes to the producers as well.

So, when does the subsidy actually work? If there are market failures – for example information asymmetry (case for MSP), high fixed costs (case for free vaccines), or positive externalities like social marginal benefit (case for subsidising education) – subsidies work better than cash.

But it's not that simple. Even in those cases, giving subsidies requires a lot of information. One needs to understand the consumer’s willingness to pay, the supplier’s marginal costs, their profitability structure, elasticity of the graphs, and ultimately analyse the equilibrium price.

There are some other qualitative arguments to this debate as well:

Paternalism is one of them. One question even debated amongst economists is, “Do the poor know what is right for them?” For instance, we want every child to study and hence have schemes like mid-day meals and free public education. But what if the poor would rather spend that money in buying more fertilisers for their land? By fixing the potential use of subsidy, are we not restricting the choices for the poor (being paternalistic)?

Cash transfers take a more liberal approach to this problem: give the poor the money and let them choose. No one wants to stay poor at the end of the day. This makes the case for cash against in-kind transfer.

Then there’s exclusion error. Why not just select the poor and give them cash? The problem is that targeting is not as simple as it sounds. It is often very expensive, has high exclusion errors, and suffers from massive corruption problems. For instance, MGNREGA, which is often credited to be self-selecting because the very nature of the scheme requires extreme manual labour for minimum wage, suffers from leakages as high as 50 percent. While the government has been trying to fix this problem by creating Jan Dhak bank accounts linked with Aadhaar cards, there is still a long way to go.

This is what makes the case for the universality and unconditionality of cash transfers. Let everyone get it. This will lower the leakages while, at the same time, helping the neediest. And as the government makes targeting more effective through bank accounts and Aadhaar, there can be schemes like the voluntary giving up of subsidy, similar to what the government did in the Ujjwala scheme.

Some of you may argue about the massive economic burden which such policies often entail. While theoretically that is true, in practice, governments often gain more because of the leakage fixing in subsidies. Kejriwal, when asked how he would fund Rs 8,000 crore for the cash transfers in Punjab, made a similar argument. He said, “The key for the government is to fix the corruption and leakages. We expect that in itself could save the government Rs 20,000-54,000 crore.”

In summary, the poll promises of cash transfers are not mere freebies. They have been economically proven to work and, if executed properly, can work miracles. Cash transfers especially to women will go a long way in bringing financial empowerment of 50 percent of the population, positively impacting women’s health and education, and reducing gender violence.

It is also expected to play a significant role in curbing the drug menace situation in Punjab, which has destroyed lives of thousands of young Punjabi men; multiple studies have shown that money in the hands of women is utilised more judiciously and productively. This is also known as the theory of “second best”, when fixing a market failure (poverty) also ends up fixing another market failure (women oppression). The positive contribution of increased consumer expenditure on GDP due to more cash in-hand can be seen clearly in the fact that Delhi has registered an impressive SGDP growth rate of 7.4 percent over these years.

To be fair, however, sound financial management will be the key to the success of this scheme. Punjab has accumulated massive debt and has a crumbling state economy. For the AAP, which boasts of being able to double the Delhi government’s budget in five years and of running one of the few revenue surplus governments in the country, this will be an uphill task. But this is definitely a progressive step in Indian politics – moving away from the politics of religion and focusing on governance and social welfare – with policies verified and stamped by economics as being impactful.

One nation, one language, one bank account

One nation, one language, one bank account