Behind Imran Khan’s condemnation of Rushdie stabbing and Pak media’s cautious response

Most of Pakistan’s media did not cover the attack because blasphemy is still considered a red line despite international pressure.

Pakistan’s former prime minister Imran Khan has often been in the news but has probably issued his sanest statement in recent times. Opposing the attack on Salman Rushdie in the British newspaper Guardian, Khan termed it “terrible” and “sad”, adding that the anger of Muslims at the book Satanic Verses was understood “but you can’t justify what happened”.

Meanwhile, Pervaiz Elahi, Khan’s foe-turned-friend and the newest chief minister of Punjab – where most of Pakistan’s blasphemy cases originate – approved of the attack. Watching a wrestling match in Lahore, Elahi said Rushdie got what he “deserved”.

Khan’s political journey

Khan has been on the receiving end of similar remarks for nearly three decades. He married his first wife Jemima Goldsmith – a British screenwriter with a Jewish background – in 1995 and has consistently faced accusations of being part of the Jewish lobby or a “Zionist stooge”. Khan supported Jemima’s brother Zac Goldsmith in his bid to be elected the mayor of London, in 2010 and 2016, and this did not go unnoticed the second time when Goldsmith’s opponent was Pakistan-origin Sadiq Khan. The opposition in Pakistan argued that Khan chose a Jewish candidate instead of a Pakistani.

Khan is an Oxford graduate who understands the gravity of the situation and is the only mainstream politician to have met Rushdie during his years abroad. Though he has consistently appeased the right-wing in Pakistan, he has also ensured that he appears modern to the international media and has been mostly, if not always, true to this condemnation of blasphemy.

Back in the day, Khan publicly refused to share the stage with Rushdie at the India Today Conclave in Delhi, but he is being courageous here – the groundwork though has been done by liberal, left-wing, and human rights activists.

Pakistan has experienced some high-profile blasphemy cases, including the assassination of Punjab governor Salman Taseer in 2011 – his son Shahbaaz Taseer was abducted by the Taliban a few months later. Khan was the only mainstream leader to have condemned this murder as well as the hero's welcome the assassin received in Islamabad. The incumbent minority minister Shahbaz Bhatti was killed soon after, and Sherry Rehman, a national assembly member who tabled an amendment to make the blasphemy law less discriminatory against the minorities, had to go into hiding.

These were episodes from a period when most people had a black-and-white acceptance of a view that everyone who disgraced holy figures should die, and many lived their life without questioning the consequences of this fanaticism. Nothing would have changed, had it not been for the handful across Pakistan who protested against vigilantism.

A dangerous mess

Rushdie’s failed assassination did not attract any crass publicity stunts; no mainstream politician or political analyst pounced on this ugly opportunity.

While section 295 linked to blasphemy in Pakistan’s penal code is a legacy of British rule that has been around for more than a century, it was made punishable by death by adding section c in 1992. The Pakistan Muslim League – the party of the then prime minister and Punjab chief minister – was the architect of this move. And the number of blasphemy accused languishing in jails has doubled since then.

A reason the law was modified was because of the fatwa against Rushdie and a paranoia that people will disrespect holy figures of Islam – this fear married bad politics and the outcome turned more disastrous than anyone could have predicted then. Pakistan became a world leader in anti-Rushdie protests, with large rallies and even an attack on the American Cultural Centre.

Things have become more convoluted. Most people have realised that unbridled provocation and murder with impunity can help no one, and international pressure has been mounting on Pakistan to save some of the accused in prominent cases.

In 2016, when Salman Taseer’s assassin was hanged, his funeral was censored in mass media even though there were widespread protests, and his grave eventually became a mausoleum. Aasia Bibi – a Christian woman accused of blasphemy whose defense led to Salman Taseer's murder – was released and swiftly repatriated to Canada.

Media under fire

In the past few years, the media has also come under the scanner over blasphemy; major news channels, morning show anchors, religious programme hosts and journalists have been facing such cases in courts.

The ambit of blasphemy is ever expanding.

When actress Veena Malik’s wedding rituals were re-enacted on a morning show with a qawali that mentioned Prophet Muhammad, it was deemed as blasphemy, and a court case involving two channels, their staff and several celebrities was launched. As the trial lingered, the show host’s career came to an end. This has also taken a sectarian turn, sparking more chaos.

Aamir Liaqat, a televangelist who died in June, blamed his arch-rival Junaid Jamshed for blasphemy, triggering an assault on the latter during a trip to the airport. In 2017, Liaqat was banned from television after he accused a group of missing Pakistani activists of blasphemy; he was eventually sacked as a Bol TV anchor.

In May, Imran Khan and his former cabinet members were accused of blasphemy when alleged supporters of Khan’s party PTI booed the incumbent PM in the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. A case was filed against Khan and others over the incident, and this was defended by interior minister Rana Sanaullah while social media wings of the ruling party tried to target Khan.

The definition of blasphemy is so fluid that anyone can come under fire, and the accuser does not have to face any consequence.

The cautious news coverage

Pakistani news media dealt with the news of Rushdie’s attack with caution. Most news outlets did not cover it because it is considered a red line. But, it was also a busy news day when the incident took place, and the stabbing was neatly tucked away.

One reason is that Pakistan is in the middle of political turmoil; Imran Khan had planned a massive jalsa in Lahore’s iconic Hockey Stadium. Additionally, the 75th anniversary of Pakistan's independence was a day away when the incident took place.

Geo, a mainstream channel, did mention the stabbing at the end of its bulletin calling Rushdie “Shatam-e-rasool” (insulter of the prophet), but no one commented on the issue, possibly because anyone who treads down this slope tends to slip. Moreover, Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority, an independent body that looks at provocative content, also forces media outlets to practice caution.

As for Imran Khan, he might have won some support abroad with the Guardian interview, but not without landing him in a tricky position. “Gustakhon ka yaar Imran Khan”, meaning “Khan, a friend of blasphemers”, has already been trending on Twitter and right-wing Tehreek-e-Labbaik has weighed in on the issue in the most provocative terms. Khan’s comments were brave, especially when a campaign like this can now endanger his safety and weaken his political position at a time when he ostensibly needs it the most.

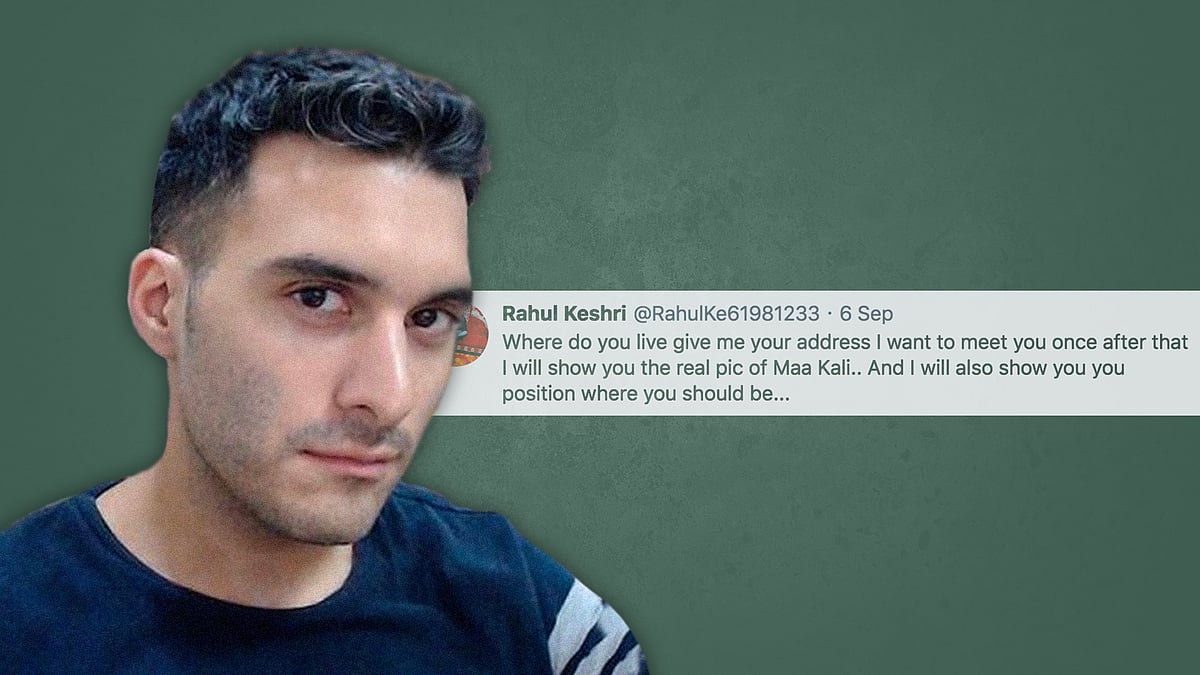

Hindutva backlash against Atheist Republic’s founder echoes Islamist reaction to blasphemy

Hindutva backlash against Atheist Republic’s founder echoes Islamist reaction to blasphemy NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.