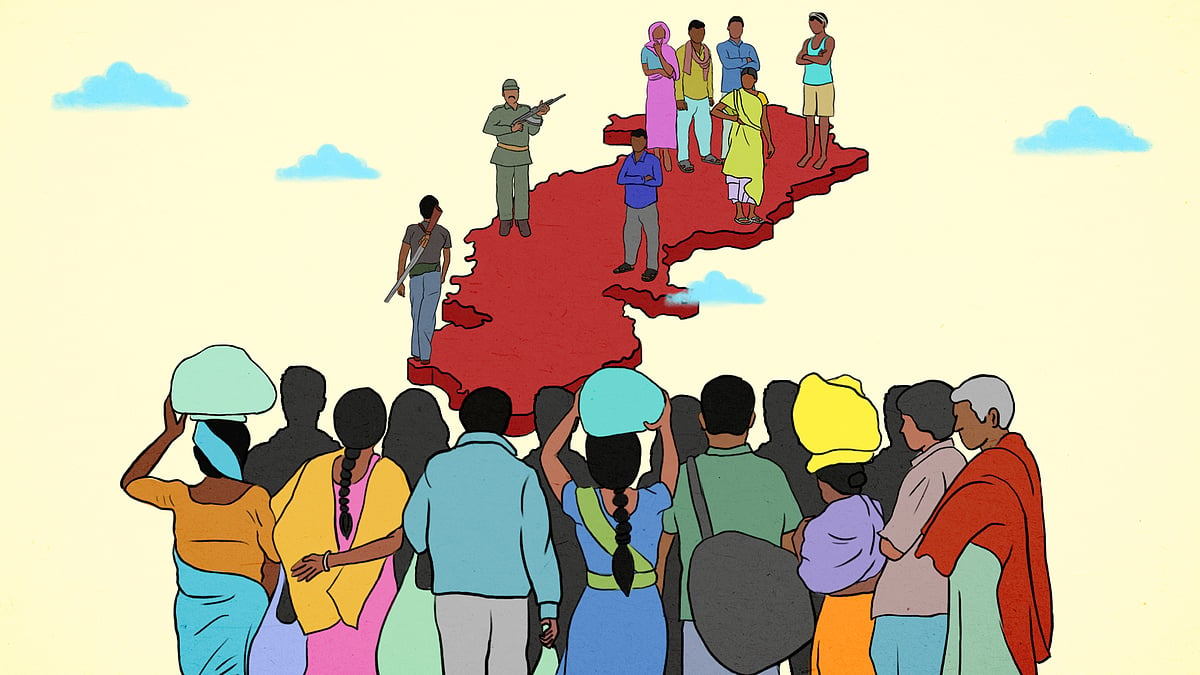

No caste certificate, no admission: Why Chhattisgarh’s displaced Adivasi children can’t go to school

Their lack of documentation means they struggle to enrol in schools and colleges.

This is Part III in the NL Sena series on Adivasis displaced from Chhattisgarh who now live in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Read Parts I and II here.

When Irmaiah was six years old, his parents quietly shipped him out of Chhattisgarh to Andhra Pradesh.

It was 2005, and the Salwa Judum’s reign of terror had taken over Adivasi villages in Bastar. In Gangarajpadu village in Sukma, Irmaiah’s parents worried about his safety. So, he and his brother, then aged 10, were dispatched across the border with an uncle – just one among 55,000 Adivasis who made their way to new lives in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

There, new challenges awaited them.

In 2009, the district collector of what was then Khammam in undivided Andhra Pradesh, filed a report with the National Human Rights Commission, saying 16,024 displaced Adivasis from Chhattisgarh had settled in Khammam alone. Of this, 6,204 were children, ranging from infants to teenagers aged 14. Around 4,025 were of school-going age, but only 2,241 had enrolled in schools.

So, while adult Adivasis struggled to make a living, settling in hamlets without water, electricity or jobs, children had their own unique set of issues. Chief among these issues was their lack of caste certificates.

In their home state, the displaced Adivasis are recognised as belonging to the Muria tribe. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, they aren’t – and they’ve long battled for tribal status. Refused certificates, they stand outside schemes for Scheduled Tribes, and their children pay the price.

Primary schooling isn’t a problem. Even remote hamlets usually have primary schools up to Class 5 around four or five km away. To study further, they can enrol in residential schools for Adivasis run by respective state governments – but the displaced Adivasis told Newslaundry they’re asked for caste certificates to enrol their children.

“In Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, caste certificates are necessary for higher education,” explained Kattam Kosa, a displaced Adivasi living in Chintalpad village in Telangana’s Bhadradri Kothagudem district. “Without it, our people find it difficult to get admission in government schools.”

Applications for these certificates are often rejected.

“The government of India has clear rules to issue ST certificates to migrant tribes,” said a senior official with Andhra Pradesh’s tribal welfare department, who refused to be named for this report. “But the procedure to grant it involves verification from the gram sabha, which also has to pass a resolution stating the applicants follow specific customs. This is where things get stuck.”

Irmaiah at his home in New Kothoru hamlet in Chinthuru, Andhra Pradesh.

An anganwadi in Chintalpad village, Bhadradri Kothegudem district, Telangana.

Couldn’t a state government intervene to smooth the process? Yet its response is best summarised by a senior official at Integrated Tribal Development Agency in Telangana’s Bhadrachalam, who told Newslaundry, “Caste certificate is just an excuse not to study. They are not interested in studying.”

Kosa added that the Telangana government issued them Scheduled Tribe certificates but “stopped” three or four years ago. There is no clarity as to why, even though it’s been often reported over the years.

Additionally, displaced Adivasis told Newslaundry they face resentment from local Adivasis. In part one of this series, Newslaundry had reported that migrant Adivasis from Chhattisgarh share commonalities with local Adivasis in Andhra and Telangana – both belong to the broad Koya tribe.

But the worry, according to a government official, is that if the displaced Adivasis get caste certificates, they will also become STs – implying “competition” for jobs and other government benefits.

Newslaundry repeatedly contacted representatives from the Integrated Tribal Development Agency and forest departments of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana for this story. None of them agreed to speak on the record for this report.

Inaccessible education

Seventeen years after Irmaiah fled Chhattisgarh, he met Newslaundry in December 2022 in Andhra Pradesh’s Chinturu.

Irmaiah is lucky, compared to his fellow Adivasis, and he knows it. He’s currently in his first year of an undergraduate programme in a government college in Chinturu. He speaks fluent English and wants to become a civil servant.

Irmaiah said he has little memory of his turbulent childhood.

“Whatever I know is from my uncle and brother,” he said. “I remember them telling me Salwa Judum was destroying everything in my village, that they were burning down all the houses and that no human being would be left. My parents sent me here to protect me.”

Irmaiah wouldn’t see his parents for six years, apart from a fleeting visit from his mother. He lived with his uncle and brother in New Kothoru, about 12 km from Chinturu. He said no one back home in Gangarajpadu knew where he’d gone – his parents were too frightened that he would be “tracked down”.

“I think my mother came once to see me. But no one from my native village knew I was alive,” he said. “My parents were scared that if someone got to know about me, they would even come here and kill me.”

In 2011, however, when his family deemed it safe enough, Irmaiah returned to Gangarajpadu. No one recognised him, he said, not even his father.

Meanwhile, Irmaiah’s brother had started helping their uncle farm their land. The uncle decided Irmaiah would go to school. He was enrolled in a special residential training centre, or SRTC, in Chinturu.

The SRTCs were established across undivided Andhra Pradesh in 2009 for the children of displaced Adivasis. This was after the National Human Rights Commission intervened and commissioned the report from the Khammam district collector. Run by NGOs and funded under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, SRTCs were alternative schools that aim to rehabilitate children into mainstream education through bridge courses.

But by 2014, both Andhra Pradesh and Telangana ended these programmes. And other schools, even government schools, began asking for caste certificates too.

Dr SK Haneef heads an NGO called Sitara Association in Khammam. Until 2013, Sitara ran the STRC in Chinturu where Irmaiah studied. He said “things were smooth” from 2009 to 2013 and they were “able to help a lot of Adivasi children with their education”.

“We were authorised to give them transfer certificates so the students could get admission in government boarding schools for tribals even without caste certificates,” he said. Government boarding schools were ideal since “students get everything for free, including uniforms, books and other necessities”. “Since most of the displaced Adivasis are not financially sound, they prefer admitting their children there. Other government schools have expenses,” he said.

But when undivided Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated in 2014, “the governments of both states stopped supporting SRTCs,” Haneef said. Government boarding schools required them to provide caste certificates, and “many Adivasi children failed to secure admission or continue their studies.”

But the government official in Bhadrachalam isn’t buying it.

“Caste certificate is just an excuse not to study,” he said, on condition of anonymity. “You give me names, I guarantee I will admit anyone in our boarding schools without any caste certificate. Many of my schools are still running much below their capacity. I can easily adjust them. But the point is they are not at all interested in studies.”

Meanwhile, Irmaiah managed to enrol in a government school with the help of Christian missionaries. He stayed in a hostel run by missionaries – he described it as “very strict” but it “helped me grow smarter”.

“It was there where I learnt English,” he said proudly. “Before that, I didn’t even know the English alphabet. I even failed in many subjects initially. But I worked hard and passed Class 12 with decent marks.” He then enrolled in the government college last year.

Didn’t he need a caste certificate for college admission? “The college authorities keep asking me to submit it,” he said. “But I keep stalling them since I don’t have it.”

The anganwadi in a Gutti Koya hamlet in Mulugu district, Telangana.

‘This reflects the apathy of governments’

New mothers also struggle. Many of the villages Newslaundry visited don’t have anganwadi centres. As a result, babies and small children do not have access to non-formal preschools or supplementary nutrition.

The few centres we found – four in Mulugu and Bhadradri Kothagudem – were run out of thatched huts without full-time staff. Their infrastructure comprised a chalkboard and posters with pictures of fruits and vegetables. There were no desks or chairs.

A senior government official, who did not want his name, designation or department revealed, told Newslaundry most of the operating anganwadis were “non-registered”, run either by villagers or NGOs.

“This only reflects the apathy of the state governments in providing basic education to displaced Adivasi children,” said Haneef. “This is why a lot of Adivasi children lose interest in education and engage themselves in clearing forests or in Podu cultivation.”

The situation is similar for other migrant tribal communities in both states, such as in Aligudem village in Chinturu, Andhra Pradesh. Located about eight km from Chinturu town, Aligudem was established in 1952 after groups of Adivasis migrated from Odisha. The village comprises 456 families from the Koya tribe. Like their Chhattisgarh counterparts, none of the children have caste certificates.

“In 2021, 104 applications for caste certificates were filed,” said Punem Padaya, the village head, “but only one got accepted.” Villager Madkam Anand said the government “used to issue” certificates until 2012-2013 but “abruptly and completely stopped” a few years ago.

Those who already hold caste certificates are told they aren’t “valid”, the villagers alleged. Madvi Pradeep, 24, for example, tried to enrol in a government college using his caste certificate that declares he’s a member of the Koya tribe. He said the college rejected the certificate and asked him to “get a new one”.

Villagers at Aligudem village in Chinturu, Andhra Pradesh.

Madvi Pradeep with his rejected caste certificate.

Kunja Jagadesh with his school transfer certificate.

“They say this one is too old. But why should I get a new one when I already have one?” he asked. Pradeep was forced to enrol at a private college, which he said is very expensive, to do a B.Com course.

Kunja Jagdeesh from Aligudem told Newslaundry his school transfer certificate from 2003 indicates he’s a member of the Koya tribe. But, like Pradeep, the local government college refused him admission so he stopped studying.

“Studying in a private college is not possible for everyone,” he pointed out. “Yearly expenses could go up to Rs 40,000. Where would I get that much money?”

Pradeep’s theory is that the administration is “worried” that the displaced Adivasis will “excel more” in education and employment opportunities than local Adivasis. And this was reflected in a conversation this reporter had with a senior government official in Chituru on the troubles faced by villagers from Aligudem. The official insisted this was more of a “local, inter-tribal” issue than an administrative one.

Chhattisgarh’s displaced Adivasis: Can they even ‘go home’ after 17 years?

Chhattisgarh’s displaced Adivasis: Can they even ‘go home’ after 17 years? Fear and longing in Bastar: For Adivasis in Salwa Judum camps, there is no way home

Fear and longing in Bastar: For Adivasis in Salwa Judum camps, there is no way homeNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.