Projects worth over Rs 12,000 crore: Joshimath’s journey from ‘development’ to disaster

Experts have warned against these projects for decades. Are authorities finally listening? Not quite.

If it had been a typical January, Auli would be bustling with tourists. Every year, crowds throng the Uttarakhand hill station for skiing, cable car rides, trekking, or simply to soak in the raw beauty of its location.

But this year, Auli is deserted. Hotel bookings are cancelled and tourists are staying away after Joshimath, about 12 km away by road, developed cracks in its buildings due to land subsidence.

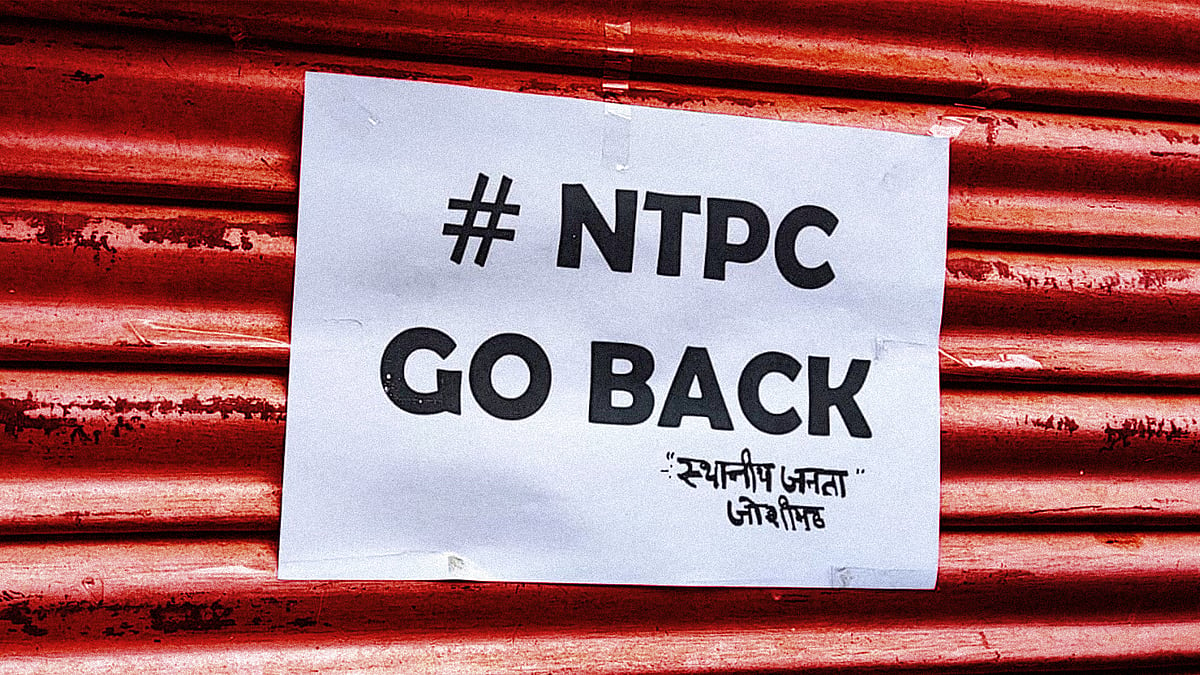

Now, Joshimath is crawling with bulldozers, police vehicles, disaster management personnel, and protesters waving signs. Poignantly, several buildings are marked with red crosses, indicating they’re unsafe and in danger of collapsing.

Evacuations are therefore underway. “There are some houses and buildings that are fine so far,” said Himanshu Khurana, district magistrate of Chamoli, where Joshimath is located. “But if there is a sudden landslide and dilapidated buildings collapse, this can affect the areas around them. So, these areas are being evacuated too.”

Darban Naithwal, 56, is one of those packing up. He lives in Joshimath’s Singhdhar and said every room of his three-story house has developed cracks.

“We initially thought we would never leave the mountain. That’s why we built such a big house,” he said. “But even before we completed this house, it’s being demolished.”

Singhdhar is one of four wards in Joshimath – the others being Sunil, Manoharbagh and Marwari – that is most affected. The administration has divided the areas into core zones and buffer zones, depending on impending danger, and about 200 families have been moved out so far.

Singhdhar also has a sizable population of Dalits, many of whom live in poverty, eking out a living through agriculture, animal husbandry or odd jobs.

Shivlal, 75, told Newslaundry that his farm has “caved in”. “Our lives are based on this land,” he said. “We used to cultivate rajma and malta and sell it in the market to run the house. But now this land is completely ruined.” Shivlal has now sent his family to temporary accommodation at a nearby school. He’s staying behind to tend to the animals.

A red cross on a building indicates it is in danger of collapsing.

There are over 150 hotels, homestays and lodges in Joshimath.

The pressure of projects

On January 13, the Indian Space Research Organisation’s National Remote Sensing Centre released a preliminary report. It indicated that between April and November 2022, Joshimath sank by 8.9 cm. But between December 27 and January 8, it sank by 5.4 cm.

Two days later, the report was taken down from the National Remote Sensing Centre’s website. The National Disaster Management Authority said some government institutions had been releasing data and “interacting with media with their own interpretation of the situation”, and warned them to stop “creating confusion”.

According to locals, Joshimath’s population has increased 50-fold over the last 100 years. As a gateway to religious and adventure tourism, it has over 150 hotels, lodges and homestays, each with an investment between Rs 50 lakh and Rs 10 crore. They were all built on debris left behind by glaciers, on stocks deposited by landslides, all while ignoring warnings made by experts over 50 years before.

As a result, Joshimath was never ready for such a burden. Geologist YP Sundriyal said it’s “surprising” that the government “never implemented any house building codes” in an area this sensitive.

Pankaj Bansal, a businessman from Haryana, owns a 27-room hotel in the town. He admitted that rules were “ignored” during construction.

“If the government makes rules, we do not follow it,” he said. “It is our fault too. Government regulations regarding number of floors, etc are there for a reason. But people do not care, thinking they’ll deal with the consequences later.”

Tourism and housing aside, it’s Joshimath’s hydropower and road projects that pressured the land. Over the last four decades, demolitions and explosions took place as part of these projects, even as experts like the Mishra committee warned against them.

Over the years, hydropower and road projects have pressured the land.

In the 1980s, the 400 megawatt Vishnuprayag power project was set up at a cost of Rs 1,694 crore. The project still functions. In 2006, the state-owned NTPC began building a 520 MW project – the Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower project – at a cost of Rs 2,978.48 crore, which was later increased to Rs 5,867.38 crore. Construction is still underway. In 2012, work began on the 444 MW Vishnuprayag Pipalkoti project – its estimated cost was Rs 2,491 crore, later revised to Rs 3,860 crore – but it’s barely 50 percent near completion.

Work is also ongoing for the six-km long Helang-Marwari bypass near Joshimath at an estimated cost of Rs 200 crore. The bypass is part of the 900-km Char Dham Yatra marg, which is described as an “all-weather road”. This Rs 12,000 crore project was inaugurated in December 2016 and work is still going on.

50 years of warnings

Locals are fed up. Across Joshimath market, posters have sprung up with shouting capitals – “NTPC Go Back”. The NTPC has denied that its project is linked to land subsidence in Joshimath, but experts have been saying for decades that heavy projects shouldn’t be constructed in the high, fragile Himalayan areas.

In 1976, for instance, the Mishra committee filed a report after land subsidence was reported in Joshimath. It warned of “disequilibrium” caused by blasting, soil erosion and lack of drainage leading to landslides, and recommended restrictions on heavy construction.

These warnings were repeated by other experts in 2006 and 2009, and as recently as 2021 following the Uttarakhand floods, when at least three reports cautioned against construction in and around Joshimath.

Saraswati Prakash Sati, a geologist attached to the College of Forestry, Ranichauri, also filed a report on the aftermath of the 2021 disaster in Chamoli. He told Newslaundry that in 2021, Nature Geoscience, a peer-reviewed journal, published research on “basal sliding” impacting glaciers in the upper reaches of the Himalayas.

“Due to this, ongoing hydropower projects that are new or currently under construction should not be allowed,” Sati said. “They are always in danger and jeopardise the lives of people living downstream.”

Evidence of this was found in Lambagad, a small village about 25 km from Joshimath on the Badrinath road. Locals blamed the Vishnuprayag power project for the devastation caused here by the 2013 floods. Now, outside the project premises in Lambagad, the government has put up a sign warning that the plant may have to be closed and that the river’s levels may increase “in case of an accidental fault in the transmission line or machinery”.

The warning sign near Lambagad.

Like other experts before him, Sati also pointed at demolition carried out for road projects.

“The slopes have been mobilised on a large scale by excavating the mountain under the Char Dham Yatra route,” he said. “Due to this, hundreds of new landslides have become active. Additionally, all the stone debris from digging is dumped directly into the rivers.”

Other experts told Newslaundry that Joshimath should be declared eco-sensitive – similar to what was done in 2012 from Gomukh to Uttarkashi – since it falls under seismic zone. 5.

“The advantage of becoming an eco-sensitive zone is that activities in that particular area are designated as allowed, banned or encouraged,” said activist Hemant Dhyani who is associated with a movement called Ganga Ahvan and is a member of the Supreme Court-appointed expert committee on the Char Dham road project. “Only this can save a historical city like Joshimath.”

Ravi Chopra, an environmentalist and chairman of an expert committee that studies the Char Dham Yatra route, said that since Independence, people did not understand the gravity and impact of developing hill towns. Now, they’re paying the price.

“In the absence of a vision, hill towns were developed indiscriminately,” he said. “Not only Joshimath, haphazard construction has taken place in Shimla, Mussoorie and Gangtok because the difference between development in hilly areas and in plains was not understood. Corruption is a big reason behind this.”

But when asked about declaring Joshimath an eco-sensitive zone, district magistrate Khurana was cautious.

“We should wait for the opinion of experts. There should be no reaction in haste,” he told Newslaundry. “The economy here is related to tourism. People are the biggest stakeholders. Ecology and environment are important but it would be good if a further decision was taken based on the opinions of people and experts.”

This report was first published in Newslaundry Hindi. It was translated to English by Utkarsh Mishra.

‘Government, don’t ignore us!’: 22 km from Joshimath, Reni’s villagers worry they’re next

‘Government, don’t ignore us!’: 22 km from Joshimath, Reni’s villagers worry they’re next  NTPC faces local ire in Joshimath, authorities probe its ‘role’

NTPC faces local ire in Joshimath, authorities probe its ‘role’NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.