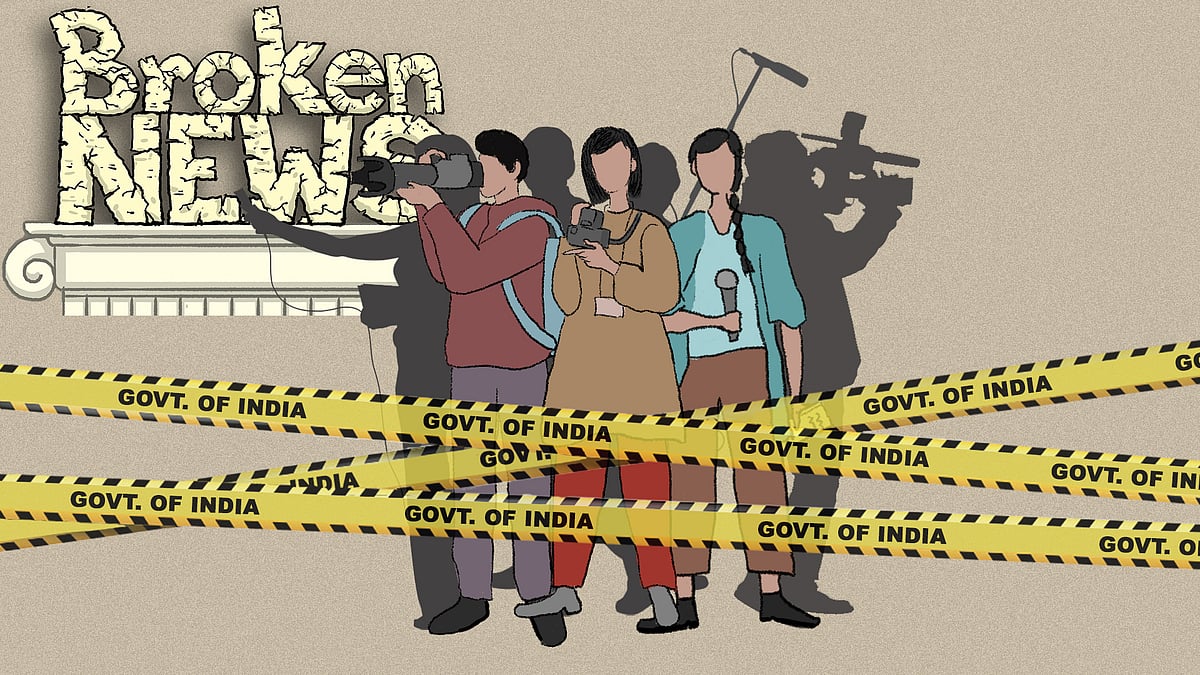

The embarrassment that is PIB Fact Check: Who fact-checks this ‘fact checker’?

The Press Information Bureau does not understand the difference between repudiation and refutation.

If it is acceptable for Supreme Court judges to exonerate themselves, and for lobbyists to undertake dubious observation missions in Kashmir, then the prospect of the government “fact-checking” journalists should not remain far behind.

In December 2019, the Press Information Bureau launched a fact checking arm simply called PIB Fact Check. It has handles on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, with a combined following of more than 1.5 lakh. A short profile of it published in the Print earlier this year claimed that its objective was “to identify misinformation related to government’s policies and schemes that are circulating on various social media platforms”.

Fact-checking involves investigating and discerning the validity of a claim. The American Press Institute tells us that fact-checking aims to “increase knowledge by re-reporting and researching the purported facts in published/recorded statements made by politicians and anyone whose words impact others’ lives and livelihoods,” adding that the exercise is “free of partisanship, advocacy and rhetoric.” The International Fact Checking Network has an entire code of principles on fact-checking.

Reporters have traditionally aimed their fact-checking guns at the government or, more broadly, at the state. In 2018, a fact-check revealed fudged data behind the Uttar Pradesh government’s claim that 99.9 percent of households in the state had toilets. Another recently debunked a claim by Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal that a family of 26 had tested positive for coronavirus. In December last year, we at Newslaundry fact-checked a bogus Uttar Pradesh police claim that the anti-citizenship law protests in Bijnor had a “communal angle”.

Since the state has vested interests in half-truths and lies, it is rather awkward that it will now fact-check those who tend to call it out. The first principle of the IFCN’s code states that fact-checkers must have “a commitment to non-partisanship and fairness”. This is important so that fact-checkers do not “unduly concentrate” on any one side.

The PIB does not meet this criteria. Most of its “fact-checks” are simply denials of media reports that are critical of the government’s Covid-19 strategy. The Indian Express, Caravan, Wire, Brut India, Imphal Times, and others, have been at the receiving end.

It’s not all bad. The PIB Fact Check debunks dubious WhatsApp forwards and social media posts too. This often comes in handy for habitual forwarders of fake news, since the fact-check comes from a government body.

But the pros end there, and the long list of cons begin.

How PIB ‘fact-checked’ the Wire

On May 21, the Wire published a report that questioned links between top Bharatiya Janata Party leaders and Jyoti CNC, a Rajkot-based company that recently donated Dhaman-1 ventilators to the Centre for the ongoing Covid-19 health crisis. These machines were shunned as substandard by doctors in Gujarat and the Puducherry government.

The report suggested that there exists a bonhomie between Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Gujarat chief minister Vijay Rupani, and Rameshkumar Virani, an influential diamantaire who has stakes in Jyoti CNC, the company manufacturing Dhaman-1 ventilators — which is perhaps why the Gujarat government approved of and acquired the ventilators in the first place.

A day later, PIB Fact Check tweeted that the report was “factually incorrect”, using the hashtag #FakeNews. It made two allegations. First, that the story was misreported because the Gujarat government did not purchase the ventilators, but received it as a donation from Jyoti CNC. Second, it said the Dhaman-1 units were “based on required medical standards”.

But both these claims are false.

First, the story clearly mentions that the ventilators were “supplied free of cost to Ahmedabad civil hospital by Jyoti CNC”. This is where the “purchasing” bit comes in. When the controversy over Dhaman-1’s quality erupted, the Gujarat government defended the ventilators and revealed that “the central government's HLL Lifecare has placed an order of 5,000 units of Dhaman-1”. It added that Puducherry and Maharashtra also placed orders “apart from orders from other countries”.

Second, contrary to claims that Dhaman-1 units meet safety standards, Ahmedabad Mirror published an incriminating report, quoting doctors and bureaucrats, that points in the opposite direction. The daily also reported that these ventilators “do not have the mandatory licence from [the] Drug Controller General of India” and that its trial “was held only on one patient”. Moreover, the ethical committee that needed to monitor the equipment “was not formed as per Medical Devices Rules, 2017”.

By this logic, if Dhaman-1 is a proper ventilator, then the PIB’s tweets constitute a fact-check.

Repudiation vs refutation

Since the PIB is a government body, its tweets are essentially a response from the Modi government. The Prime Minister’s Office, which the Wire claimed it tried to contact for the story, did not respond to the news website. (In fact, journalists have seldom received responses from the PMO in recent years.) Once the story was published, there was a campaign to discredit it on Twitter using troll armies and loyalist hate blogs like OpIndia.

The PIB sells denials as fact checks. It does not understand the difference between “refutation” and “repudiation”. To repudiate is to deny and reject, but to refute is to disprove. A repudiation requires a PIB babu to prepare a “fake news” graphic for Twitter, but refutation comes with the heavy duty of painstakingly demonstrating a claim to be false. This sole process is why many decent journalists earn wages, however meagre.

Richard Nixon repudiated the claim that his administration was involved in the Watergate break-in, but the Washington Post refuted him. China has only repudiated the claim that the novel coronavirus was created in one of its labs, but scientists have refuted the claim altogether.

In mid-April, Caravan reported that the Indian Council of Medical Research-appointed national task force of 21 scientists did not even meet once in the week preceding Narendra Modi’s declaration of Lockdown 2.0. The ICMR rejected the claim in a terse tweet. Once again, the PIB surfaced with its fact-checking cape to label the Caravan report as “false” and “baseless”.

In response, reporter Vidya Krishnan asked the ICMR to produce the minutes of these meetings. She added that the magazine had emailed ICMR multiple times before the story was published and did not receive any response.

Both the ICMR and the PIB did not respond to Krishnan’s requests on Twitter. Krishnan told Newslaundry that the government bodies did not respond to her requests. She did not receive the meeting minutes, or a response to her emails.

Earlier this month, the Indian Express reported that the Delhi police thinks that a popular audio clip of Tabhlighi Jamaat’s Maulana Saad might have been doctored. The Delhi police called the report “factually incorrect”. Once again, instead of any serious due diligence, PIB Fact Check simply regurgitated this and added that the Express story was based on “unverified sources”.

The reporter, Mahendra Manral, was questioned by the Delhi police later that week. Express has stood by the story so far, claiming it “is based on conversations with sources and officials aware of the probe against Maulana Saad”. Like the Wire and Caravan, Express also alleged that it received no response from the Delhi police before the story was published.

There are many other such “fact-checks” by the PIB: a Scroll article on children in Bihar eating frogs due to food shortage; a Brut video on quality issues with personal protective equipment kits; an Imphal Times report on the lack of Covid-19 infrastructure in Manipur; an Asian Age report on religion-based Covid-19 mapping; a Daily Excelsior report on Kashmiri students stuck in Delhi.

In this hour when genuine information is crucial, the fatuous body of work produced by PIB Fact Check adds to the prevailing obfuscation by the Modi government. The information flow on the Covid-19 crisis is scarce and twisted, and the daily briefings have dried up. Since March, there have been multiple instances of journalists being intimidated for their critical reporting of the ongoing health crisis. The government itself has spread false news about screening passengers, paying for train tickets of migrant workers, and wage arrears to MGNREGA workers, among others.

But minus the cynicism, if someone at the PIB is really interested in fact-checking, if even one kindred spirit thinks that digging up facts is worth their time, if a conscientious employee finds orders by senior officials cringy and wrong — then we can offer some respite. The AltNews website has a “methodology of fact-checking” page that lays down the elementary steps of fact-checking. FirstDraft offers short, crisp and free online courses on disinformation and how to bust it, including one on coronavirus. Fact-Checking Day by the IFCN also offers some great resources in this area.

We hope those working at PIB peruse these websites and learn a thing or two about fact-checking. The Indian media needs to be held to account and scrutinised, but the PIB isn't offering us this. So far, they have been serving the government. It’s time they serve the public.

***

The media needs to be fair and free, uninfluenced by corporate or government interests. That's why you need to pay to keep news free. Support independent media, and subscribe to Newslaundry.

Government should view journalists as allies, not adversaries. Especially in a pandemic

Government should view journalists as allies, not adversaries. Especially in a pandemic