‘The only journalist who cared’: Memory of scribe killed after refinery report lingers on in Maharashtra

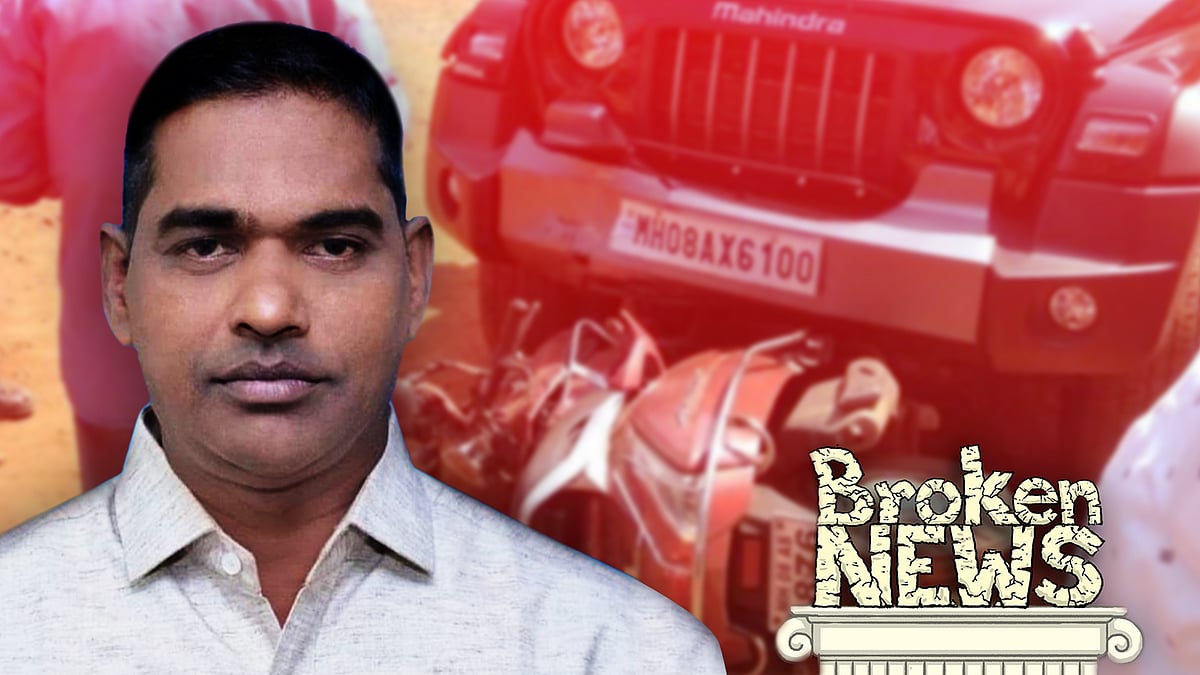

Shashikant Warishe was mowed down allegedly by the subject of his last report on a controversial refinery.

“He was the only journalist who covered the refinery protests…From the time the protests began until now, he covered everything…other newspapers barely gave coverage to the issue. People here liked him a lot because he was the sole journalist who cared about their issues.”

That’s how Dipak Joshi remembers his friend Shashikant Warishe, a journalist who was allegedly murdered by the subject of his last report – a land agent linked to a controversial refinery project in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri.

The Mahanagri Times journalist’s death has triggered protests by the media fraternity in Maharashtra, and brought attention to the Ratnagiri Refinery and Petrochemicals project – which is to be set up in different parts of the Konkan region and has been facing protests by farmers and locals over the last two years.

But had it not been for Warishe’s reportage, the agitation could have gone unnoticed. And many like Dipak Joshi, who is an activist part of the resistance against the refinery, unheard. For over two years, Warishe had been documenting farmers’ voices against the refinery: about concerns linked to livelihood and environment, the protesters’ letters to ministers, the lack of a response, and alleged corruption.

“He used to say that he would write what he would see; no matter who it was against. He was offered bribes to not write against the refinery but never accepted them,” said Amol Bole, president of the Barsu Solgaon Refinery Virodhi Sanghatana – an organisation protesting against the project.

The journalist’s friends and acquaintances said that unlike many others, he never accepted bribes to drop the refinery reports.

“He was a dashing reporter; never did a story without concrete evidence. He was associated with me for 10 years and was non-corrupt throughout,” said Sadashiv Kerkar, editor-in-chief of Mahanagari Times.

Police inaction against the accused?

Pandharinath Amberkar, the man accused of murdering Warishe by crushing him under his car, has been arrested. But locals alleged that he has been in a hospital in Ratnagiri since his arrest owing to “chest pain”. He was initially booked for culpable homicide but the police pressed murder charges after local protests.

Amberkar, who locals claim is a BJP worker, has a criminal record. Two years ago, he had allegedly tried to mow down a sarpanch’s son. More recently, he allegedly threw stones at anti-refinery protesters inside a court complex. An FIR was filed but no action was taken.

The land agent is part of the pro-refinery lobby in Ratnagiri. In his last report, Warishe wrote how Amberkar was publicising his pictures with the prime minister, Maharashtra chief minister and deputy chief minister on banners across roads, thanking them for the refinery project.

The Rajapur police remained unavailable for comment. A series of questions has been sent toJanardan Parabkar, the police inspector investigating the case. This report will be updated if a response is received.

Meanwhile, journalists from the state protested outside local administrative offices on Friday. They demanded the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act against the accused, an SIT to probe the “conspiracy”, a fast-track trial, and Rs 50 lakh compensation for the journalist’s family. The Press Council of India has also taken suo motu cognizance and sought a report from the Maharashtra chief secretary and DGP.

‘He didn’t think he would live very long’

Warishe’s friends and acquaintances describe him as a passionate journalist who cared for the poor and went out of his way to help those he knew.

Like most journalists in rural India, Warishe did not get paid for the news that he gathered but the ads that he got. In his case, that wasn't a lot. Amol Mhatre, his colleague at Mahanagari Times, told Newslaundry that he would get a commission for the ads that he would bring, but he wasn’t the type of journalist who could try to convince people to give ads, so he would mostly get paid based on ads brought on big days like Republic Day and Diwali.

“He was attacked from behind so didn’t have a chance. But if he was attacked from the front, he would have fought,” said Mhatre, who knew him for more than a decade.

Warishe was the only earning member of his family and is survived by his mother and 18-year-old son. Soon after he had cleared his matriculation exam, his father died and his brother-in-law took him to Ratnagiri, where Warishe did odd jobs before entering the world of journalism. He never looked back.

Warishe received threats from officials he used to write against, but it didn’t deter him from doing his job.

“I asked him a couple of times whether he was scared. He said he wasn’t, and that we all had to die someday. He used to tell me that he didn’t think he would live very long, but that he would live like a lion for as long as he does,” said Babu Gowalkar, a close friend of Warishe.

Gowalkar last met Warishe three weeks ago in Mumbai, and is now left with the memory of a friend who went out of his way to help him when his father died of Covid. “People that time didn’t want to touch us but he told me not to worry and that we will send my father off the way he deserves. He came to my village, and helped us.”

“I still haven’t told my mother about his death. After I came back from the village, she asked me how he was and if he ate food. I don’t know how to tell her the truth as we were like a family and he was like her son.”

Why Maharashtra journalist’s murder reflects poorly on status of press freedom in India

Why Maharashtra journalist’s murder reflects poorly on status of press freedom in India