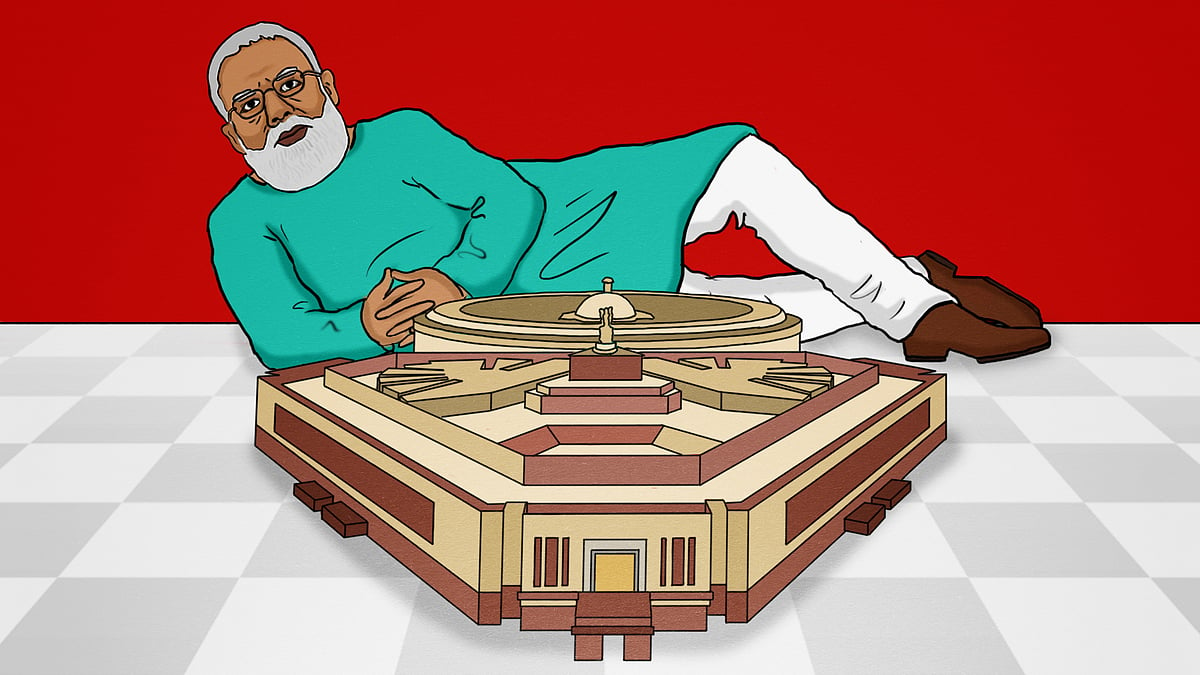

With the new Parliament, Modi’s BJP continues with the themes it’s invoked since 2014

The BJP is working towards the erection of a parallel iconography and cementing India as a civilisational state.

In some ways, the inauguration of the new Parliament building – conducted amid the symbolism of a spectacular ceremony and the acrimonious rhetoric of many opposition parties – mirrored the fragmented realm of national politics.

At the same time, it showed some continuity of themes since the summer of 2014, when the BJP-led government came to power under Narendra Modi. Besides blending elements of “nutan and purantan”, the new and the ancient, to recall Modi’s evocative phrase on the occasion, the ceremony significantly marked continuity in a key part of the party's political messaging of the last nine years.

Three of them are identifiable in different forms: the ideological imprint of the BJP on conducting affairs of state, Modi’s presence as the centrepiece of the party’s idea of public projection, and the erection of a parallel iconography in different forms to either counter or add to pre-2014 public narratives.

First, the invocation of India as a civilisational state, with a stream of Hindu identity as the leitmotif of its national personality, has been a constant strand for the last nine years. In the party-government fusion, various public functions have been symbolic instruments to convey this idea. This, however, has also tried to have a sense of proportion by placing other identities as adjuncts to this larger frame of national edifice.

So, for instance, along with the elaborate ceremony involving a sceptre called the sengol in the new Parliament building, there was also a multi-faith prayer ceremony involving different religions.

Since 2014, the Modi-led BJP has been viewed as embracing religious symbolism as a part of its conduct of public affairs. This was a theme that surfaced when Modi performed the Ganga aarti at Varanasi after the BJP won a landslide mandate in the 2014 Lok Sabha poll. It was also when Modi prostrated on the steps of the old Parliament building when he first entered the house. A section of social scientists and scholars viewed such gestures as addressing a long-felt disconnect between the everyday belief system of a country teeming with millions of believers, and an imposed, visibly artificial space of public conduct seen in state affairs.

“To understand the Modi regime, one has to accept that Modi was therapeutic for a generation that felt that elite modernisation was a hypocritical affair conducted by groups which used words like ‘secular’ to dismiss the thought processes of a middle-class more rooted in religion and folklore...By articulating such anxieties, Modi soothed their wounded subconscious. And this ‘wounded class’, tired of pseudo secularism, elite cronyism and majoritarian hypocrisy, voted him to power,” wrote sociologist Shiv Visvanathan in 2014.

It isn’t that the early years of the Indian republic were devoid of civilisational or religious motifs in state conduct. As early as the commencement of the constitution in 1950, the subtext of such recollections can be seen. The very first article of the Indian constitution reminds Indians of their land as Bharat, declaring, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a union of states.” It is important that drafters used the more ancient nomenclature of Bharat, not the more contemporary Hindustan. The yearning for identifying civilisational ancestry was visible.

Similarly, the historical imagery of the ancient Mauryan empire in India’s state emblem is another example. It’s an adaptation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath. It’s also interesting to recall that when the constitution was drafted, its calligraphed copies were sent to artist Nandlal Bose, who decorated all 22 parts of the document with art depicting India’s journey from the Indus civilisation to the mid-20th century. This implied a lot of historical depictions, such as the Mauryas, Akbar, Guru Gobind Singh and Shivaji. At the same time, it had religious imagery too, such as the chapter on fundamental rights having a scene from the Ramayana.

The prime minister often makes references to democratic traditions in ancient India. Even these aren’t new to the public sphere. It was seen, for instance, in how Dr BR Ambedkar viewed some political practices in ancient India. In his book Ambedkar: A Life, Shashi Tharoor wrote: ““Whereas some saw Ambedkar, with his three-piece suit and formal English, as a Westernised exponent of Occidental constitutional systems, he was inspired far more by the democratic practices of ancient India, in particular the Buddhist sanghas. As chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar argued that the constitutional roots of Indian republicanism ran deep.”

Second, the new Parliament building has been justified on various logistical grounds like space, capacity and even technological upgrades. There could be a separate exercise in examining the merits of such arguments. But, at the same time, it’s clear that the Modi government is keen on erecting a parallel iconography of historical figures while also leaving its imprint on contemporary times through architecture and other symbolic constructs. In 2018, for example, the inauguration of the Sardar Patel statue, also called the Statue of Unity, in Gujarat’s Kevadia, tried to do a bit of both – drawing on the legacy of a historical figure and symbolising it through a towering statue.

In some states like Uttar Pradesh, such an appropriation has also taken the form of reaching out to some caste groups by appealing to their pride by symbolically resurrecting their historical icons. Attempts to draw on the historical memory of figures like Suhel Dev can be seen as part of this move. Sometimes, such a parallel iconography is pitched as a critique of the wilful neglect of such figures during the long rule of Congress-controlled historical narratives. So, while fitting into an ideological frame, these moves also find place in the immediate vortex of electoral politics.

Moreover, in the personality brand of politics seen in Modi’s style of political messaging and ideological pitch, it’s clear he is inclined to leave an imprint on the architecture of power corridors in the national capital. Such an impetus isn’t implausible in the move to have a new house for the country’s apex legislative body.

As the 1927 building housing India’s Parliament gives way to a new building, amid the invocation of its civilisational identity and religious traditions, the prosaic work of legislation now needs to turn over a new leaf. The task of debating and dissecting issues and making laws cannot be outsourced to extra-parliamentary realms – certainly not the combative diatribe of social media. In the present 17th Lok Sabha, only 13 percent of bills have been sent to parliamentary committees. This either shows a hasty law-making spree or the sharp government-opposition divide that is undermining the legislature’s crucial function of thorough study and meticulous scrutiny of proposed legislation.

Moreover, the delimitation exercise is also likely to augment the number of legislators. It can only be hoped that the expansion in numbers does not add to the din of partisan rigidities, but puts heads together towards the onerous task of law-making and the exercise of deliberative functions of the body.

NL Interview: MP John Brittas on the disconnect between media and parliament

NL Interview: MP John Brittas on the disconnect between media and parliament Central Vista as New India? It could actually end up being the Really Old India

Central Vista as New India? It could actually end up being the Really Old IndiaNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.