In Patna, will opposition parties finally write the first draft of the 2024 alliance?

From seat-sharing to regional differences to keeping the rank and file happy, there’s much to iron out before next year.

As the June 23 meet of 18 opposition parties in Patna draws closer, efforts are underway to set the right tone for the meet. Bringing together the widest range of opposition parties in recent times, the Patna meet is expected to work towards the first draft of alliance-making for the 2024 Lok Sabha poll.

However, there are a number of challenges to be grappled with before common ground yields a working arrangement.

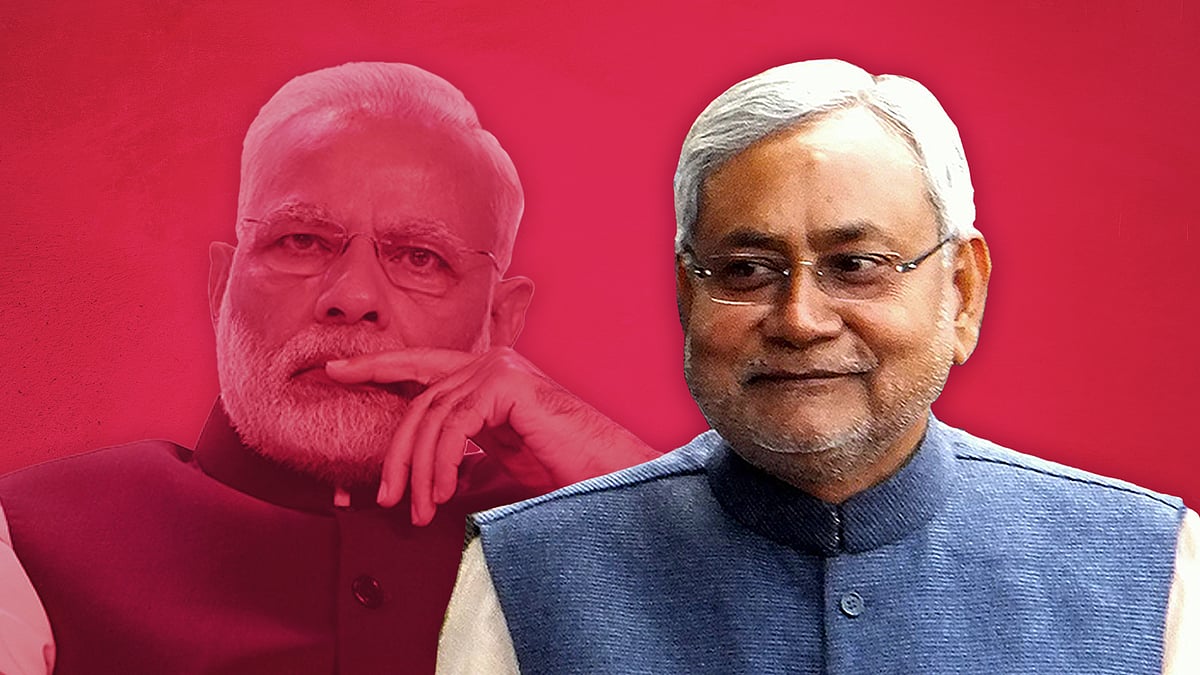

A glimpse of one of the primary challenges was seen last Sunday at a party function of the meet’s host, Bihar chief minister and Janata Dal United head Nitish Kumar. Party president Rajiv Ranjan, alias Lalan Singh, had to chide some party workers when they raised the slogan “Desh ka PM kaisa ho, Nitish Kumar jaisa ho” – loosely translating to “who should be the country’s PM, it should be like Nitish”. Singh sternly cautioned the workers against projecting Nitish for the top job at the centre, lest it derail the process of opposition unity.

The idea of postponing the decision on the leadership of the proposed alliance – which, in practical terms, means the face for prime ministership – may make strategic sense. But it may also sow the seeds of discontent and distrust.

This, however, isn’t a new proposition. In the heyday of coalition politics at the centre, most strikingly from the last decade of the 20th century to the first decade of the current century, this was a standard code while stitching pre-poll pacts. But then, the leaders of the two pivots of rival alliances – the Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party – were generally seen as the prime ministerial faces of the alliances. While that still holds true, some new claimants on the national challenger space may not readily accept that position.

The Patna meet includes parties like the Aam Aadmi Party and Trinamool Congress, both of which were earlier not even keen to be part of any alliance featuring the Congress or its allies in any arrangement. As such, the strong messaging of Congress primacy in the alliance may not go down well with them.

Nitish has been foregrounding the Congress’s role in any effective opposition alliance. Keeping the leadership issue in abeyance is aimed at bringing more allies into the fold. One can’t be sure how the Congress top brass – to be represented in Patna by president Mallikarjun Kharge and Rahul Gandhi – will view such reluctance to identify a leader. Buoyed by its victory in Karnataka and expecting more electoral gains in assembly polls later this year, the Congress might see itself as placed with more elbowroom.

But the question of leadership right now may not be a sticking point – as long as it remains undecided.

The opposition might also be wary of how projecting a face will end up playing into the hands of the BJP-led alliance. Juxtaposing any such leader against prime minister Modi, the BJP’s campaign might find the proverbial fight pitch. At the same time, the failure to project a leader might be attacked as a sign of confusion and disarray in the opposition camp.

In view of how the political scene has unfolded in recent years, the Congress is alert to the fact that new political forces in the opposition must not nudge it from its default position as the national challenger to the BJP. This has been a constant part of its political messaging over the last two years – a period in which some regional forces were seen as growing at its expense and seeking a national frame.

The Patna meet is also likely to explore the idea of fielding the alliance’s joint candidate in the Lok Sabha poll. This is premised on harnessing the strength of constituent allies vis-à-vis the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance in different parts of the country. But this move – to curtail the division of opposition votes and bolster an index of opposition unity – is harder than merely forming an alliance. It will have to overcome points of resistance, not only among parties but within parties. If the push for one-on-one contests becomes the governing logic for seat-sharing in this alliance, the process will have to surmount many roadblocks.

While this will be easier in states like Tamil Nadu, where the Congress will concede its claim to regional forces like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, it will be tougher in states where the Congress is fighting any of the parties that will constitute the national alliance. The local units of the Congress will, for instance, be against any arrangement with the AAP in Delhi and Punjab. They view Arvind Kejriwal’s party as a beneficiary of the Congress’s slide in both places, and have voiced their concerns about the Congress top leadership possibly overlooking this regional factor.

Similarly, the Congress unit in West Bengal, led by Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury, has been vociferously critical of the TMC government in the state. It wouldn’t be easy to bring both parties on the same page for the state poll. In south India, Kerala may pose the same riddle for the Congress where it leads the principal rival alliance against the Left government in power. Keeping aside these state-specific dynamics has its own set of risks.

Even in states like Uttar Pradesh, where the Congress has been reduced to a marginal force, the tie-up with regional forces like the Samajwadi Party may carry the scars of earlier failures of the combine. In the 2017 assembly poll, while the electoral rout was another issue, both parties showed little signs of coordination. Since then, they haven’t been eager for an alliance. They avoided partnering in the 2019 Lok Sabha poll and in the 2022 assembly poll.

At the same time, the Congress will be more comfortable about forming alliances in Maharashtra, where it recently ran a state government with its Maha Vikas Aghadi partners: the Nationalist Congress Party and Shiv Sena (Uddhav).

While an inter-party divergence in such arrangements is expected, it will be interesting to see how the parties manage resistance from within. These experiments often leave a sizable number of party leaders and cadres sulking at their reduced chances of getting a ticket or having their way in executing poll campaigns. Many alliances fail to realise their potential because the ground workers of constituent parties cold-shoulder these overnight tie-ups. An example is the dismal performance of the SP and Bahujan Samaj Party alliance in Uttar Pradesh in the last Lok Sabha poll.

So, it’s crucial that the parties take their cadre along while stitching alliances, with political messaging percolating down to the rank and file.

In many ways, the trajectory of opposition alliance-making at the centre is different now from how coalition politics shaped other short-lived experiments – like the Janata government of the last 1970s or the National Front and United Front governments of the late 1980s and mid-1990s. The political churn of the intervening decades modified old determinants of alliance-making and also introduced new dynamics, both at a regional and national level.

In attempting to produce the first draft of a potential new alliance, the Patna meet will try to cut through numerous contradictions to find common ground for next year’s election. If the points of convergence prevail over divergent interests, the 2024 poll may witness a dual-alliance bipolar contest.

Road to 2024: There are two kinds of Opposition alliances, but how will the Congress fit in?

Road to 2024: There are two kinds of Opposition alliances, but how will the Congress fit in? JDU-BJP breakup: Why Nitish can afford to play maximalist again

JDU-BJP breakup: Why Nitish can afford to play maximalist again

NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.