Delhi police in 2020 and Mumbai police in 1992-93: Why consistent media focus matters

Delhi police’s shoddy investigation into the February 2020 riots has been widely reported and criticised. In contrast, police savagery and equally shoddy investigation during the riots of 1992-93 in Mumbai was largely ignored by the press, despite a commission detailing them.

The transfer of a sessions judge rarely makes headlines, but Delhi additional sessions judge Vinod Kumar Yadav’s transfer did, thanks to his relentless criticism over the last 10 months of the Delhi police’s investigation into the riots in the capital in February 2020. This criticism was widely reported in the Indian media, which has sustained its coverage on the riots and their aftermath, including riot cases.

Reading Yadav’s remarks on the Delhi police’s investigations – remarks that were, incidentally, echoed by other sessions judges as well as the high court judge who granted bail to some of the accused – one was left wondering at the Delhi police’s misconduct, which had, as the judges pointed out, cost many Delhi residents their liberty. A number of these accused residents were Muslims. Some got bail and some were even discharged.

Thanks to sustained media coverage of the tumultuous events in the capital over the last few years, we have seen Delhi police lose its credibility as an impartial force. We’ve seen it target peaceful protesters (many of them Muslims) but take no action against BJP leaders giving inflammatory speeches. The recent judicial criticism of their investigation raises doubts about even their competence.

Is the Delhi police’s misconduct during the February 2020 riots unique? Alas, no. The police’s disregard for procedure, failure to collect substantial evidence, refusal to register first information reports, is a pan-Indian problem, as was evident in the way the Mumbai police investigated the riots that ravaged the country’s financial capital in December 1992 and January 1993, after the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

Sample this:

In Pratiksha Nagar, one of the worst affected areas, four cases relating to 200 Muslim homes being damaged in January 1993 were closed by the police as “A summary” (which means they’re classified as true but undetected). When a deputy commissioner of police re-opened the files, he found the victims had given written complaints naming the looters, but these complaints had been removed from the files by the investigating officer.

The night after the Babri Masjid was demolished, two Hindus were killed in Bandra. Despite receiving letters by two local Muslims who claimed to be witnesses and named the alleged killers, the police closed the cases, again labelling the case as A summary. A total of 1,358 cases, which constituted 60 percent of all the riot cases, were closed as A summary cases by the police.

On January 11, 1993, polio-afflicted Abdul Mannan was attacked and burnt to death behind the fish market at Pratiksha Nagar. His sister, who witnessed his killing, recognised four Shiv Sainiks as part of the mob. Mannan’s father named them in a written complaint to the police, but the complaint was “lost”.

A written complaint to the police by Jabbar, a resident of Ghatkopar, named his son Feroz’s nine killers. But it was not included in the case papers by the investigating officer, though he had a copy of Jabbar’s letter to the Police Commissioner giving the same details. The case was closed as A summary. When it was re-opened, the police clubbed the murder, which took place on January 10, with an unrelated murder that took place on January 11; a surefire way for the investigation to fail. In Ghatkopar, 39 of 62 riot cases were classified as A summary. Muslims were the victims in 34 of them.

These are just a few instances of the way the police investigated the worst riots to have hit Mumbai. This damning information about the Mumbai police’s cavalier and even malafide investigations of riot offences was among the revelations that came out during the hearings of the Justice BN Srikrishna Commission’s inquiry into the riots and were commented upon by him (Vol I, Chapter IV, Paras 1.13, 1.14, Chapter V Paras 1.5, 1.6). The Commission’s proceedings, which lasted from 1993 to 1998, were open to the public. Yet, hardly any of this made news despite the sensational content.

Initially, when Mumbai’s newspapers reported the Commission’s hearings, a glimpse of the police’s partisanship and unprofessional conduct did come through. But in 1994, the legal proceedings regarding the March 12, 1993, serial bomb blasts started, and editors thought it would be too much to carry two sets of legal reports every day. The coverage of the Commission hearings virtually stopped. If the coverage had continued, maybe the one-sided narrative surrounding the Mumbai riots – which perpetuates the stereotypes of violent, heavily-armed Muslims; helpless and outnumbered police officers; brave Shiv Sainiks who protected Hindus – would not have persisted.

For many, the central image of the Mumbai riots was the Radhabai Chawl incident of January 7-8, 1993, in which six Hindus (five of whom were women and children) were burnt alive by Muslims. The mayhem against Muslims that followed has often been justified as a “backlash” by Hindus. Yet, by using police documents and cross-examining policemen and eyewitnesses, the Srikrishna Commission dismissed the backlash theory and held Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray responsible for Muslims being violently targeted in January. (Vol I, Chapter II, Para 1.27) The Commission also established that had the police been more sensitive in its treatment of unarmed Muslims who came out on the streets to protest against the Babri Masjid demolition, the violence in December may not have spread (Vol I, Chapter II, Paras 1.3, 1.26).

Ordinary citizens don’t read commission reports. They do, however, read newspapers. Had the press given space to the Commission’s hearings, the chasm between the perception of Hindus and Muslims, of what happened during the riots, may have narrowed. Hindus continue to believe those one-sided narratives; Muslims continue to feel they were only victims, not aggressors.

The Srikrishna Commission’s report was tabled in 1998. In 2000, the then Chief Justice of India AS Anand put pressure on the Maharashtra government to act against the 31 policemen indicted by Justice Srikrishna, specifically naming the seniormost, former police commissioner Ram Dev Tyagi. But when an FIR was filed against Tyagi under Section 302 (murder), headlines in the English press were about the demoralisation of the police who, we were told, were only doing their duty. Readers were not encouraged to recall how Tyagi had led a raid on a bakery and madarsa, which left eight innocent and unarmed Muslims dead.

Imagine if newspapers had reported the unforgettable testimonies of survivors of that raid – how a bakery employee was shot dead even as he begged on his knees that he was innocent; how a handicapped maulana was swung from the first-floor banister of the madrasa, then pulled back, kicked down the stairs, shot and left to die as he pleaded for water. Would these acts have been seen by readers as policemen doing their duty?

This instance of police savagery might then have ranked alongside the Radhabai Chawl incident, as one of the defining incidents of the Mumbai riots. Instead, Tyagi was discharged within two years and today, the trial of some of the other accused policemen meanders along, with both prosecutors and judges regarding it as just another old case. Sadly, even the survivors of the raid no longer care.

In one of the worst cases of the riots, 10 accused under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act of stripping, mutilating and then burning alive a 19-year-old Muslim and lynching her uncle, were acquitted on flimsy grounds, even though the girl’s mother, who had herself been stripped but managed to escape, identified nine of the accused. The trial went unreported. Had it been reported, perhaps the government would have been forced to appeal.

It’s worth keeping in mind that some of the worst cases of the Gujarat 2002 riots actually saw justice being done. One of the reasons for this was that the media did not stop covering the violence and its aftermath. This didn’t happen in Muzaffarnagar 2013, though the riots were widely reported. Was this because editors would have had to send reporters to the villages in Muzaffarnagar where the violence took place and district courts where cases were conducted? Are the Delhi riot cases being diligently followed up because no special effort is required by the media to cover them?

Whatever the reason, the consistent reportage of the Delhi riot cases has reduced the Delhi police’s reputation to zero. One cannot help but wonder whether those most culpable in Mumbai’s riots – the policemen who were supposed to protect citizens – would have been punished had the media not abandoned the story.

'Officer who wrote chargesheet forgets he is not a storyteller': Umar Khalid’s lawyer

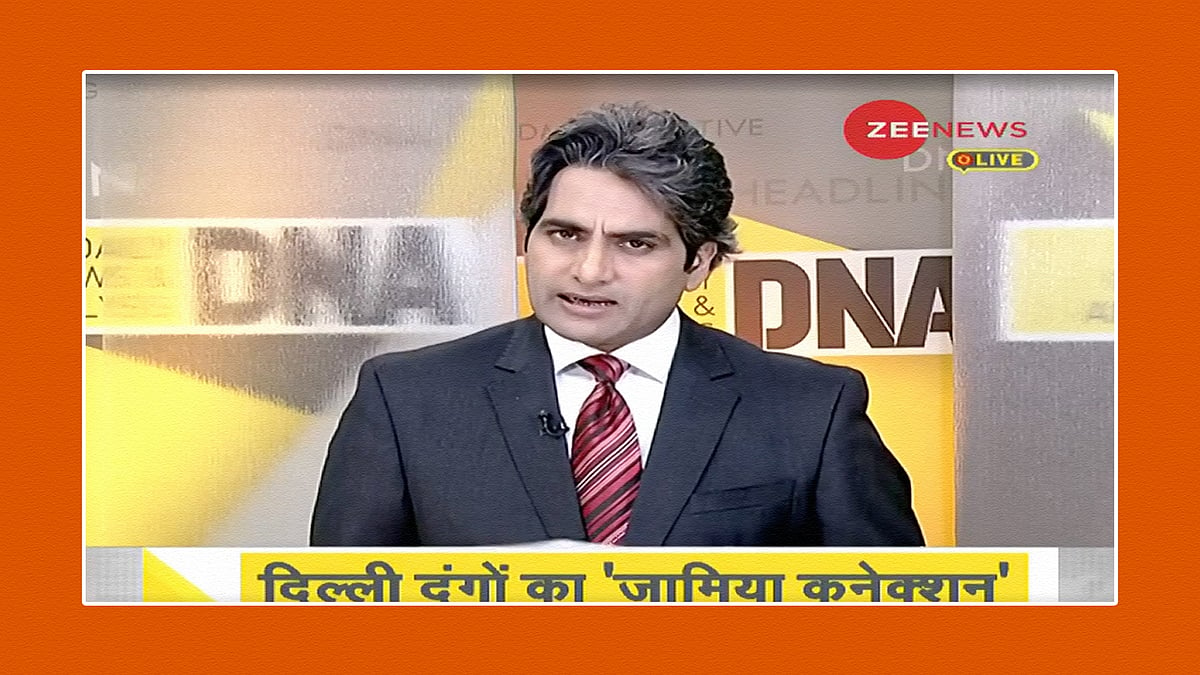

'Officer who wrote chargesheet forgets he is not a storyteller': Umar Khalid’s lawyer  How Zee News is trying to prejudice the Delhi riots trials

How Zee News is trying to prejudice the Delhi riots trials