India’s criminal law overhaul isn’t offering us a new engine, but the same car with a paint job

If the aim was to reform the criminal justice system, the exercise would’ve seen the Evidence Act as the place to start.

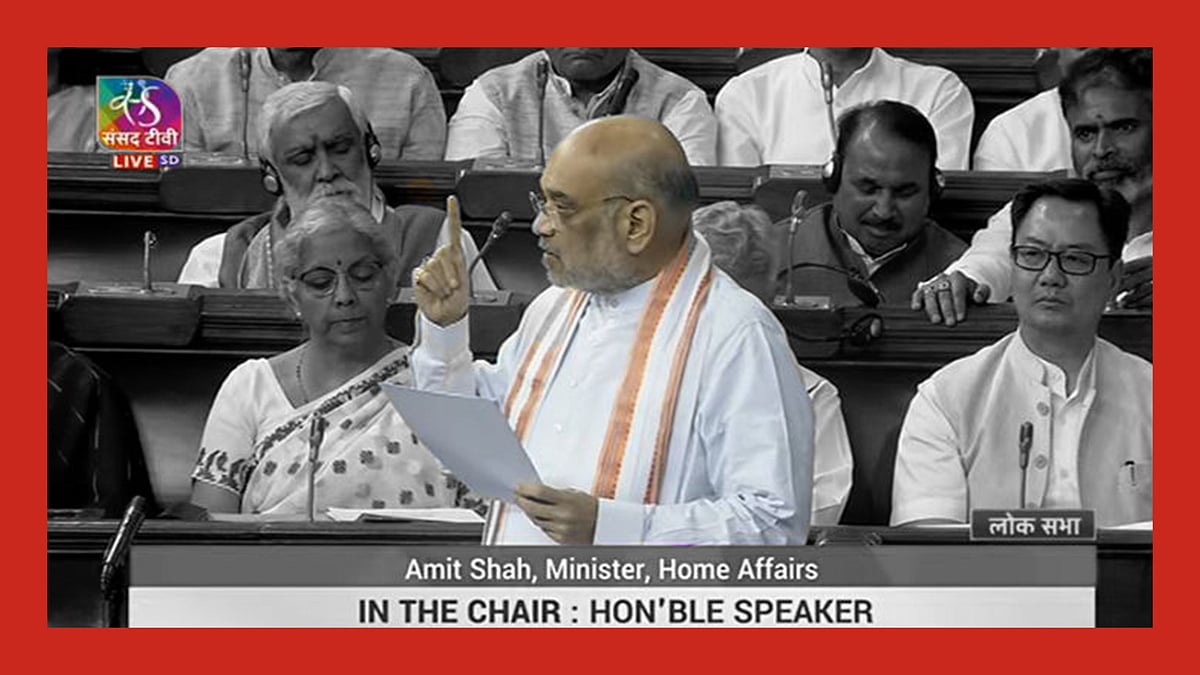

On the last day of the monsoon session of Parliament, the Union government ambushed the opposition, if not the entire country, with the announcement that it was tabling three new pieces of proposed legislation, to replace the trinity of laws that have been the bedrock of administering the criminal law.

These bills, prepared following an undemocratic and uber-secretive consultation process of which very little remains known even today, have since been referred to a parliamentary committee for consideration and may well fall by the wayside as the government takes on more ambitious endeavours such as ‘One Nation One Election’. Nevertheless, the move represents arguably the most important legislative development in criminal law for decades and demands careful engagement and attention.

So far, this engagement has come in the form of reports by reputed organisations and several op-ed pieces by both academics and practitioners of law; the consensus view emerging that, overall, much is left to be desired by the move. The focus of discussions has primarily been the proposed changes in context of the Penal Code of 1860 and the Procedure Code of 1973, and not the Evidence Act of 1872. Presumably, due to the sheer absence of change that the new draft Bharatiya Sakshya Bill brings to the existing scheme under the Evidence Act [see the P39A annotated comparison here].

Here, I want to flip the tables, and focus only on the Evidence Act in the ongoing conversation about the draft laws. I will try and convince you that the clearest indication of the present reform attempt being distinctly ersatz is presented by the sheer absence of any reform imagined within the realm of the Evidence Act.

The Evidence Act – the fulcrum on which the system rests

In the era of unparalleled delays in the criminal justice system, hardly anyone looks past the events of arrest and bail after a case is lodged. The idea of deciding questions of guilt or innocence through a trial is like a mirage – something hazy in the distance, visible, yet not achievable. But this trial is what the entire criminal justice system is designed towards conducting. Investigations, of which arrests are a critical part, are legal processes designed to gather material which can be presented as evidence at trial, the reliability of which shall be tested through the prism of cross-examination, for a court to decide whether it is convinced or not.

What is admissible as evidence and what is not, what is relevant to prove facts, who must prove them, and how do we decide what is reliable – all of these, and many more issues, are matters that are governed by the Evidence Act of 1872. At its heart is a detailed scheme explaining logical connections between facts, to show how one fact may be relevant towards proving the existence of another. This scheme of relevancy is the primary test to decide whether parties can lead evidence to prove facts. In other words, evidence that is relevant, is admissible. A second test of admissibility is found in sporadic provisions across the 1872 Act, which either lay down express conditions for proving certain facts or barriers against proving them. For instance, wills made by deceased persons must be proven a certain way. Similarly, proving that confessions were made to police officers is almost entirely barred.

In short, the Evidence Act is the lodestar which determines how the criminal justice system works. So, if someone comes along and says that the criminal justice system is broken and needs fixing, looking hard at just how the Evidence Act works is perhaps a good place to start.

Finely aging wine?

By all accounts, most lawyers and academics love the Evidence Act of 1872. Its scheme detailing the relevancy of facts is wonderfully detailed. Its rules are (mostly) logical and reasonable. And it has withstood the test of time, like finely aging wine.

Or has it? The Evidence Act of 1872 was written at a time when the language was very different from what it is today. It has, some might say, a rather Victorian style to it that tends to confuse rather than crystallise the point. But text is hardly the problem here.

Far more important is the recognition that the Evidence Act was not designed to deal with abstract theoretical notions of how to prove facts, but to facilitate conducting both civil and criminal trials in real world settings i.e., courts in British India. In the century that has gone by, there have been considerable changes to that setting. Some of the most significant ones being the wholesale rejection of trials by jury (or assessors) for trials conducted by individual judges, and the constitutional recognition of certain aspects of personal liberty which directly impact evidence gathering.

These are not ‘mere’ changes, but fundamentally alter the way trials operate. A good example is how issues regarding the admissibility of evidence are concerned. As I mentioned above, there is a barrier against introducing confessions made by defendants to police officers. However, this is not a watertight barrier, and allows ‘so much’ of that confessional statement to be introduced into evidence as may be linked to the discovery of facts. Looking at anything from that statement that is beyond this small connection would be to consider inadmissible evidence. Further, if whatever statement made had been obtained after coercing the defendant, then this would be a direct breach of the constitutional guarantee against compelled self-incrimination.

In a jury trial, the layperson was not concerned with these niceties of law, and the judge is tasked to ensure that inadmissible evidence was kept out of the factual matrix of the jury by deciding such issues before the trial. But, in a bench trial, the same judge now does both functions. This creates an impossible situation where the judge must look at the material to determine its admissibility, and if she concludes it is inadmissible, somehow erase whatever impression that this inadmissible piece of evidence left on her mind. In effect, the judge is asked to perform the impossible feat of un-ringing the bell to protect fundamental rights.

The Bharatiya Sakshya Bill

You would think that concerns as those highlighted above would have been pre-eminent for any group or legislator or committee – since we do not know who or what was or is exactly involved in the drafting process, it is best to be inclusive – that was tasked with a ‘reform’ agenda for criminal trials. But a look at the Bharatiya Sakshya Bill, tasked with repealing and replacing the Evidence Act, reveals otherwise.

It is apparent that besides rearranging a few provisions, no effort has gone into looking past the bare text of the law and to think about the kinds of problems being created by its operation at the ground level. This is not a reform, but at best a re-organisation and renaming of the existing laws and hoping that things start working better once we do that.

If anything, effort seems to have gone in largely to bring the many illustrations within the 1872 Act in tune with some yardstick of ‘geographical correctness’ or ‘political correctness’ that whoever was in charge of this process had. Thus, references to Lahore in the existing illustrations have been proudly done away with, replacing it with Ladakh (draft section 9) and Chennai (draft section 19); references to ‘baniya’ (existing section 32) have been replaced with ‘businessperson’ (draft section 26). At the same time the turgid text of the provisions and illustrations themselves remain the same.

The one notable effort on a substantive issue has been the attempt to harmonise the law on how to treat electronic evidence, a thorny issue ever since it came up with amendments in 2000. This is a complex field of problems, consisting of complicated provisions and multiple court decisions rendered over the past 23 years. It appears that the Sakshya Bill has sought to equate paper documents with electronic records, by amending the definition of ‘document’ within the law itself. But then, if that had been done, there was no need to go ahead and selectively insert ‘electronic record’ in some clauses but not others, which reintroduces confusion.

Even more confusing in this regard is the retention of the certification clause for electronic records (existing section 65-B, draft section 63). The whole purpose for having this clause was a call within the existing Evidence Act to not equate documents and electronic records, but to only do so if the certification requirement was fulfilled. But if now documents include electronic records, and there is an express clause that says electronic records shall be treated at par with paper records on any questions of admissibility (draft section 61), why retain the certification requirement which deems electronic records to “also be a document” and only then renders them admissible? Especially, as this requirement had already been criticised as redundant and dropped in jurisdictions from which it had been borrowed in the first place.

Not more than a fresh coat of paint?

Going by the speeches made while introducing the three new draft laws, the country was being promised a brand new engine for powering the vehicle of the criminal justice system. Instead, on closer inspection, one can see that what is on offer is the same car with the same stuttering engine, but a fresh coat of paint replacing ‘Evidence’ with ‘Sakshya’, or Lahore with Ladakh.

If this was a reform effort, committed to actually achieving the stated goals of reducing delays in the system, making it more accessible, and reducing pretrial incarceration, it would have understood that the Evidence Act was the place to start, and not the place to be left for last.

As the translated title of that eternal book by Yashpal goes, This is not that dawn.

The writer is a Delhi-based lawyer. He specialises in criminal law, evidence, and procedure.

Sedition ‘repealed’, death penalty for mob murder: Three new bills to overhaul criminal justice system

Sedition ‘repealed’, death penalty for mob murder: Three new bills to overhaul criminal justice systemNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.