Bhupesh Baghel and the subtle art of keeping voters distracted

Communal strife, persecution of Christians and a Hindutva overdrive have sidetracked issues linked to tribal rights in the state.

The 88-year-old father of Bhupesh Baghel, the Chief Minister of Chhattisgarh and the Congress party’s Other Backward Castes mascot in the Hindi belt, was dismissed as a crank by political experts we spoke to, when we discovered that the father was sent to jail by his son’s government in September 2021.

Nand Kumar Baghel was remanded in judicial custody for 15 days for offending religious sentiments after he made statements against the dominance of Brahmins and Vedic Hinduism in Chhattisgarh. The CM, not only used the incident to claim that he was an impartial administrator but also milked every moment of the attention it generated to burnish his pro-Hindu credentials.

“The CM’s father is just a loudmouth and a little senile,” said one Raipur-based expert about Nand Kumar, who we later discovered has been working with Lohiaite, Ambedkarite and Buddhist groups since the 1960s. “He has no political significance. Why do you want to meet him in the middle of the election season?”

We were looking to speak to the allegedly eccentric man to understand the eccentricities of ‘Chhattisgarhiya' politics.

In a state where more than 95 percent of the loal population is either Adivasi, Dalit or from the Backward communities, why would the Chief Minister allow his father to be arrested for speaking against Brahmanism? Why did the father fail to make a mark after six decades of anti-caste activism in a region with such a large caste-oppressed population? And what tactics has the son employed to emerge as one of Chhattisgarh’s most powerful political leaders?

Unfortunately, the senior Baghel has been in poor health. “He has had a very eventful political life and loves to share stories. The father and son are poles apart,” a close aide said as he politely turned us away. “But we can’t let Nand Kumarji strain himself. You should speak to people in the movement about him.”

Moving away from noted poll experts, who invariably happened to be from the privileged communities, The News Minute spoke to intellectuals and activists from the lowered castes and religious minorities to understand the supposed insignificance of the father’s ideology and the son’s predominance in the electoral arena.

The persecution of Christians

The local intelligentsia and reports in the media offer many explanations for the spectacular rise of Bhupesh Baghel, who most punters say might return for a second term. There is talk about the popularity of his agricultural and direct benefit schemes. His advocacy of the caste census and growing influence as an OBC leader in north India, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. His fight to increase the OBC quota and introduce 82 percent reservations in the state. His success in building a political narrative around local or ‘Chhattisgarhiya’ pride to outflank the BJP, which has been using the Prime Minister as their mascot. They also credit him for Chhattisgarh’s emergence as the state with the lowest unemployment rate in the country.

In all this fawning, Baghel’s increasing affinity for right-wing majoritarianism is either downplayed as ‘soft Hindutva’ or justified as pragmatic politics tailored for the times we live in. But the situation on the ground appears grim.

There have been nearly 500 major incidents of Christian persecution since the Baghel government took charge in the last week of 2018, according to statistics compiled by the Delhi-based United Christian Forum, which maintains a helpline for persecuted Christians in Chhattisgarh. That’s more than 100 cases per year.

Sources in the UCF who did not wish to be identified said that their data doesn’t capture the actual reality on the ground. Their work is hampered by the police and volunteers have been harassed and attacked by religious vigilantes several times.

An overwhelming majority of the incidents compiled by UCF happened in the Adivasi-dominated southern districts of Bastar, Kondagaon, Kanker, Narayanpur, Dantewada, Sukma, Bijapur and Dhamtari. In a majority of these cases, families who have adopted Christianity were chased out of the village, denied access to common resources and their properties were looted by their neighbours. In many cases, the mortal remains of Christians that were buried inside village limits were exhumed and desecrated.

The districts where these incidents are rampant also fall under the all-important Dandakaranya or DK zone of the underground Maoist party which runs its own Kangaroo courts called Jan Adalats.

On the question of Christians, the disagreement between the BJP and Congress appears to be over who is doing a better job of suppressing the community’s growth.

In 2021, the year which saw some of the worst attacks against Christians in Chhattisgarh, the BJP alleged that religious conversions were rising under the Baghel administration. Instead of countering the polarising and misleading statements with facts, Baghel chose to show that he too, was committed to preventing Christian conversions. “The maximum number of churches were constructed under BJP rule in Chhattisgarh,” he was quoted saying in response to the BJP’s allegation.

There have been 141 incidents of Christian persecution this year. Of these, 85 cases were recorded in Bastar alone. Along with Bastar, the Maoist strongholds of Sukma, Dantewada, Bijapur and Kondagaon accounted for 130 of these 141 incidents.

The latest incident was recorded on October 31 at the Badanji village in Bastar after the death of an Adivasi Christian man named Somaru Kashyap. The Gram Sabha or tribal council passed a resolution that Kashyap could not be buried in the village limits unless his family performed ‘Ghar Wapsi’ or reconversion.

The local police had decided to back the tribal council’s resolution and prevented the family from burying the body in their own land. A frantic message to the people in Delhi who run the UCF helpline read, “Victim family being forced for Ghar Wapsi. Situation is critical.”

One of the biggest Ghar Wapsi campaigns in the state was on December 18 last year, when large and frenzied mobs, armed with crude weapons, started chasing out Christians as part of a coordinated attack in 35 villages falling under the Narayanpur and Kondagaon districts. By the end of the day, over a thousand Christian families were suddenly homeless, even as the police and district administration stood by and watched.

A Christian volunteer based in the southern districts who helps document cases of Christian persecution told TNM that many of these families have still not been able to return to their homes and pointed out that the correct term to describe them would be IDPs or Internally Displaced Persons. The United Nations describes IDPs as, “Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalised violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised border.”

The volunteer kept changing our plans to meet and ultimately preferred to speak on the phone through an encrypted app. “In these regions, Maoists roam openly, but as a Christian pastor, I have to hide from everybody, even the police,” said the volunteer, claiming his life is in danger because of his activism. “The attitude of the government can be gauged from the attitude of the police.”

He said that Christian persecution has been a defining feature of the Sangh Parivar’s mobilisation in the tribal regions of central India for at least four decades. However, he alleged that the law and order situation had gone out of hand in Chhattisgarh under Congress rule. “Under the BJP, we were at least able to file FIRs. Now, for every case to get registered, we have to approach the Superintendent or Inspector General of Police or the District Collector. There appears to be an unsaid rule that our cases should not be registered. The police have also been filing cases against us, accusing us of forcible conversions,” he said.

The volunteer shared a copy of a writ petition, filed before the Raipur High Court in the thick of all the electioneering, by Sumitra Mandavi, a tribal Christian woman from the Chhote Paroda village in the Lohandiguda Tehsil of Bastar. Mandavi is seeking the court’s intervention to harvest the standing crops on her family’s farm. The tribal council has decreed that they will not be allowed to harvest crops from their land because they practised Christianity. She said that her family is under pressure to abandon their faith and perform Ghar Wapsi.

In her petition filed on Wednesday, November 8, she said that she was approaching the High Court after the district administration failed to respond to her urgent appeal. The petition also reveals that the tribal council prevented one of the deceased family members from being buried in their land in June this year.

The volunteer said that the tribal councils in the state have started acting like independent republics whose rules can contravene the Constitution. He said that Congress leaders have been playing an active role in encouraging the illegal decrees of the Gram Sabhas in the name of promoting local self-governance and tribal autonomy. "Both Congress and BJP leaders are against Christians," he said.

Tribal councils or Kangaroo courts?

After years of dithering, the Baghel government finally delivered on a key poll promise by passing the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) in 2022. PESA allowed for the creation of Gram Sabhas in addition to the elected Gram Panchayat. The Gram Sabha is a general council of every registered adult resident in a village falling under areas reserved for Adivasis groups under Schedule 5 of the Constitution.

An interesting feature of the Christian persecution in the state has been that the incidents before the passage of PESA were more spontaneous and violent. “Now, in a twisted show of democracy, things are planned and decided openly in the Gram Sabha, and then the police are called to execute the illegal order. Then the entire village turns up to goad the police as they evict the Christians,” said Degree Prasad Chauhan, the president of the state unit of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL). He pointed to a clause in the PESA Act which empowers the tribal councils to pass diktats on matters relating to the preservation of local heritage, culture and customs. “One thing that the Sangh Parivar, Congress, left-liberal upper castes and even the Maoists agree upon is that Adivasi culture should be protected. But what is that culture, is it Hindu culture, is it Gondwana culture?”

Adivasi faith systems have been the subject of much study. The Hinduisation of Adivasis in central India started several centuries ago, particularly among the Gond tribes, many of whose rulers had adopted gods from the Vedic pantheon as early as the 14th century. Our research led us to reams of peer-reviewed anthropological work by Dalit and Adivasi scholars documenting how Vedic Hindu gods such as Shiva and Ganesh were appropriated from the Gond tribe’s deities Shabhusek and Ganapati. Yet, there is no denying that today, the worship of the Hindu version of these gods is widespread among the various tribes of Chhattisgarh. The Gonds in particular, celebrate Hindu festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi and Mahashivaratri with a lot of fanfare, although their rituals might differ from upper caste Hindus.

Degree, who hails from the Satnami Scheduled Caste and identifies as a Dalit Ambedkarite, said there is very little resistance from the left and ultra-left to the Sanskritisation of Adivasis. “They will talk about Hindutva when Adivasis join militant Sangh organisations, but they have no clear position when the Hindu faith is superimposed on Adivasi culture,” he said, and added caustically, “Their fight is against American imperialism, the IMF and the World Bank. I suppose the fight against Brahminism in Chhattisgarh is too small compared to the revolutionary dream of liberating workers of the world.”

Degree said that despite the many complications arising from questions of faith, culture and customs among Adivasis, civil society organisations backed the clauses of the PESA, which empower Gram Sabhas to legislate on these matters.

“My Ambedkarite worldview allows me to see the basic problem with PESA is that it puts enormous power in the hands of an unelected body. The writ of a village is often the writ of the people who are powerful in that village. Ambedkar differed very sharply with Gandhi on the question of Gram Swaraj (village republics) and Panchayat Raj institutions, saying it will promote the most undemocratic tendencies of people in rural India,” he said.

He said that the ancient Adivasi working-class culture was based on the worship of nature’s resources and not supernatural beings. According to him, Hinduisation has given birth to many superstitions including caste-like systems that promote inter-generational power structures.

“The sons of priests and shamans, who are very powerful in Adivasi society, are inheriting these positions. This is not how things worked traditionally. Some families and clans are becoming more powerful than others. PESA encourages the emergence of such power blocs,” he said.

–BR Ambedkar, speaking during the Bombay Legislative Council on Village Panchayats Bill debates on October 6, 1932.

Is it possible to expect this panchayat to be an impartial body of judges? Let us consider the facts as they are. No honourable member of this House, I am sure, will deny faction feuds do not rent that very few villages. Not only are there quarrels among the Hindus themselves, but there are quarrels between the Hindus and the Mahomedans, and these quarrels are of no ordinary importance. They are serious. I would like the Honourable Minister and the House to consider whether a panchayat elected in an atmosphere of this sort would be impartial enough to distribute justice between men of different castes and men of different creeds. That is a proposition, I submit, which the House and the Honourable Minister should consider seriously.

The next question I would like to ask is, does the Honourable Minister expect that the judiciary he is bringing into being will be an independent judiciary? Sir, what is his proposition? His proposition is that the judiciary shall be elected because that is what the provisions for a panchayat mean. The panchayat which will administer justice will be a panchayat elected by the village’s adult population. I would like to ask him whether he expects that a judge who has to submit himself to the suffrage of the masses will not think twice before doing justice and whether, while giving justice, he is offending the sensibility of the voter. Suppose there was a Hindu-Mahomedan riot; suppose a Mahomedan was brought up before a panchayat for an offence triable by the panchayat; suppose one Hindu member of the panchayat thought that there was a justice on the side of the Mahomedan.

Does the Honourable Minister and does the House think that this gentleman, who may have to submit himself to an election within the course of a few months or a year, will think that he ought to do justice to the Mahomedan rather than keep his seat? What will he do? The panchayat which will administer justice will be a panchayat elected by the village’s adult population. I would like to ask him whether he expects that a judge who has to submit himself to the suffrage of the masses will not think twice before doing justice and whether, while giving justice, he is offending the sensibility of the voter.

Suppose there was a Hindu-Mahomedan riot; suppose a Mahomedan was brought up before a panchayat for an offence triable by the panchayat; suppose one Hindu member of the panchayat thought that there was a justice on the side of the Mahomedan. Does the Honourable Minister and does the House think that this gentleman, who may have to submit himself to an election within the course of a few months or a year, will think that he ought to do justice to the Mahomedan rather than keep his seat? What will he do?

Unlike Gandhi, who believed that the village is the basic unit of democracy, Ambedkar argued that an individual is the basic unit of democracy. Although Ambedkar was opposed to the way village republics were imagined by Gandhi, he was not entirely opposed to the principle of local autonomy and self-governance.

During the Bombay Legislative Council debates in October 1932, he climbed down from his opposition to the Panchayats Bill on the condition that provisions were made for special reserved seats and the so-called untouchables, who were a minority in every village, and for women.

Reiterating his discomfort with Gram Swaraj on November 4, 1948, during the Constituent Assembly debates, Ambedkar said, “What is the village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism?” When Gandhians tried to make panchayats a basic unit of India’s democratic institutions during the drafting of the Constitution, Ambedkar pushed for the subject to be included in the directive principles of state policy. This left it to the state legislatures within the federation to implement Panchayat Raj and frame rules according to their discretion.

The PESA Act introduced by the Baghel government makes the Gram Sabha more powerful than the elected Gram Panchayat. “Like Ambedkar was not entirely opposed to Gram Panchayats, I am not entirely opposed to Gram Sabhas. There was a specific objective behind the people’s campaign demanding PESA,” said Degree, “The objective was to empower the Adivasis against powerful mining companies from outside exploiting tribal land for nearly a century. And that is where Baghel has cheated the people.”

He pointed out that the demand from various progressive movements was that Adivasis should be made stakeholders in matters concerning their Jal-Jangal-Jameen or water, forests and land. “The Baghel government has inserted a very clever clause which says that the Gram Sabha must be ‘consulted' when their lands are notified for acquisition. The demand was, however, that their ‘approval’ should be sought for land acquisition and that they should be able to collectively bargain compensation and rehabilitation,” he said.

If Baghel manages to defeat the BJP, as some pundits are predicting, and return for a second term as Chhattisgarh’s CM, the celebrations won’t be limited to the Congress’ Chhattisgarh camp. Given that the BJP hasn't projected a CM candidate, his victory will be hailed across the country as a defeat of Narendra Modi by critics of the Prime Minister's Hindu nationalist politics. In such an event, we can also expect commentators to analyse it as a defeat of Modi-Shah’s brand of politics and the big corporations that finance it.

But the way the land acquisition clauses of the PESA Act have been drafted to benefit mining corporations raises serious questions about Baghel’s commitment to protect Jal-Jangal-Jameen. It appears the misuse of PESA for anti-Christian mobilisation is working in favour of the mining companies making a beeline to acquire land in one of India’s most resource-rich states.

A Buddhist father and his Hindu son

Our curiosity about Nand Kumar Baghel led us to a fraternity of young Ambedkarite neo-Buddhist activists and scholars in Raipur who held him in high regard. The fraternity – a mix of Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs – has launched multiple platforms over the last few years to spread the ideas of Ambedkar, Kanshiram, Navayana Buddhism and Adivasi culture. They have been organising an annual Buddhist festival at Sirpur and Adivasi festivals under the banner of Chhattisgarh Cultural and Heritage Foundation.

An estimate of the group’s social influence can be had from the fact that Bhupesh Baghel attended their Buddhist fest in Sirpur, knowing fully well that the organisers are some of the most vocal critics of his government’s policies.

Under the banner of another organisation called Hum Bharat Ke Log (we, the people of India), the group has been organising public demonstrations at Raipur’s main Ambedkar statue for the last five years. This has included the celebration of Buddha Poornima, Christmas, non-Vedic tribal festivals, Constitution Day, as well as birthdays of important anti-caste leaders such as Jyotirao Phule, Ambedkar and Kanshiram.

The group has also held commemorative events for Ravana and Mahishasura, considered demons by Hindus but worshipped by many tribal groups. The group’s most provocative event of the year, however, is the celebration of Lord Macaulay’s birthday for his contribution to modern education. They know full well that he is loathed by the Hindu right for allegedly westernising education in India.

Nand Kumar has been a frequent guest at the group’s demonstrations at the Ambedkar statue. They described him as a mentor in the anti-caste movement while regaling us with stories about fights between the father and son. “Did you know that Nand Kumarji is a committed Buddhist? For 40 years, he has been organising ‘Varsha Vaas’ (annual retreats) for Buddhist monks,” one of them said.

In 2001, the state government banned a book by Nand Kumar titled Brahman Kumar Ravan Ko Mat Maro, which talked about the virtues of Ravan. At the time of his father’s book ban, Bhupesh Baghel was the minister in charge of revenue and infrastructure development in the Ajit Jogi-led Congress government.

They narrated the much-publicised feud between the two in 2019 after the death of Bindeshwari Baghel, the CM’s mother and Nand Kumar’s wife. The two Baghels had a public spat over the last rites and ultimately divided her ashes. The father performed Buddhist rituals with his share, and the son performed Hindu rituals with his.

“Did you know that the most spectacular attack on Bhupesh Baghel’s flagship Hindutva project — the Ram Van Gaman Path — was made by his father?” asked one of them. As part of the project, the Baghel government identified 52 forest sites for development to honour the belief that these locations were visited by the Hindu deity Ram.

On May 18, 2020, Nand Kumar led a few dozen activists, mostly Gond Adivasis, and trooped to a remote forest site in the Tumarkhurd village of Dhamtari district, where the state government had announced the construction of a Ram-Lakshman temple as part of Ram Van Gaman project.

He tore down the billboards announcing the government project. In its place, he put up a board announcing that the site would be used to establish a Buddha Vihara. He also laid the foundation stone for the construction of a research institution to study indigenous medicine called Budhadev Ayurvedic Treatment Research Centre. In a press statement, he said that Budhadev who is worshipped by Gond Adivasis is actually the Shakyamuni Buddha.

Brahminism in the land of Buddhism

After the ice-breaking session at the expense of the Baghels, the group’s most prominent leader, Naresh Kumar Sahu, who is a postdoctoral fellow at Raipur’s PRS University, settled down for a short lesson on Chhattisgarh’s ancient heritage and modern politics.

The state’s electoral politics is dominated by the land-owning but the educationally backward Sahu and Kurmi communities, who form the two largest OBC groups in the state. The Baghels are Kurmis, and Naresh is a Sahu.

“The anthropological fact about our two communities is that we were once Buddhists and animists who were pushed down the social ladder as Shudhras with the emergence of Brahmanical Hinduism,” said Naresh, “Instead of fighting the structure that oppressed us, many of our leaders adapted themselves to it and accepted the superiority of Brahmins.”

The lowered caste Sahus and Kurmis became influential with the dawn of electoral democracy. In the new India, political power was determined by land and numerical strength, not social status, he said.

“But, this newfound power brought them closer to Brahminical Hinduism instead of pushing these Shudhra communities to reclaim their non-Vedic heritage,” Naresh said, “A handful of leaders like Bhupesh Baghel might have learnt how to win elections, but they still have to go the Brahmins and Banias for their money and moral approval. After all, they control the bureaucracy, the judiciary, the media and the biggest chunk of the private sector funds. They are the permanent structure. Politicians come and go.”

Naresh’s fraternity is building discourse to revive Buddhist and indigenous culture. This brings them into a direct contest with Bhupesh Baghel’s Ram Van Gaman project.

“A majority of the 52 locations chosen for the project are either ancient Buddhist or Adivasi religious sites. As a group of scholars and researchers, we have been working towards sharing archaeological evidence with leaders of anti-caste social and political organisations,” Naresh said.

Naresh said his fraternity is just a small intellectual collective networked with a cross-section of SC, ST and OBC mass organisations. He said that most of the non-BJP and non-Congress parties in these elections are backed by these mass organisations.

The formations Naresh referred to include the Bahujan Samaj Party, the Gondwana Ganatantra Party, Johar Chhattisgarh Party, Amit Jogi’s Janata Congress, and Arvind Netam’s Hamar Raj Party.

Although they are working in silos, all these political parties are experimenting with a political line that combines regional identity with some form of anti-caste assertion. Some of them might not even qualify as progressive. Naresh Sahu, on the other hand, lobbies his ideas with leaders of all of these parties. He shared leads about them, which we obviously followed, and that makes for a separate story altogether.

Many of the contesting candidates from these parties might end up losing the elections, perhaps even forfeit their deposits. Yet, they collectively pose a challenge in these bipolar elections dominated by the BJP and Congress.

In a recent interview with the journalist Rajdeep Sardesai, Bhupesh Baghel said these parties can be expected to garner more than 7 percent of the votes. Clearly, these non-BJP parties pose a greater ideological threat to his so-called pragmatic politics.

This report has been published as part of the joint NL-TNM Election Fund and is supported by hundreds of readers. Click here to power our ground reports.

From Kashmir to conversions, with Himanta in Chhattisgarh’s ‘jinxed’ constituency

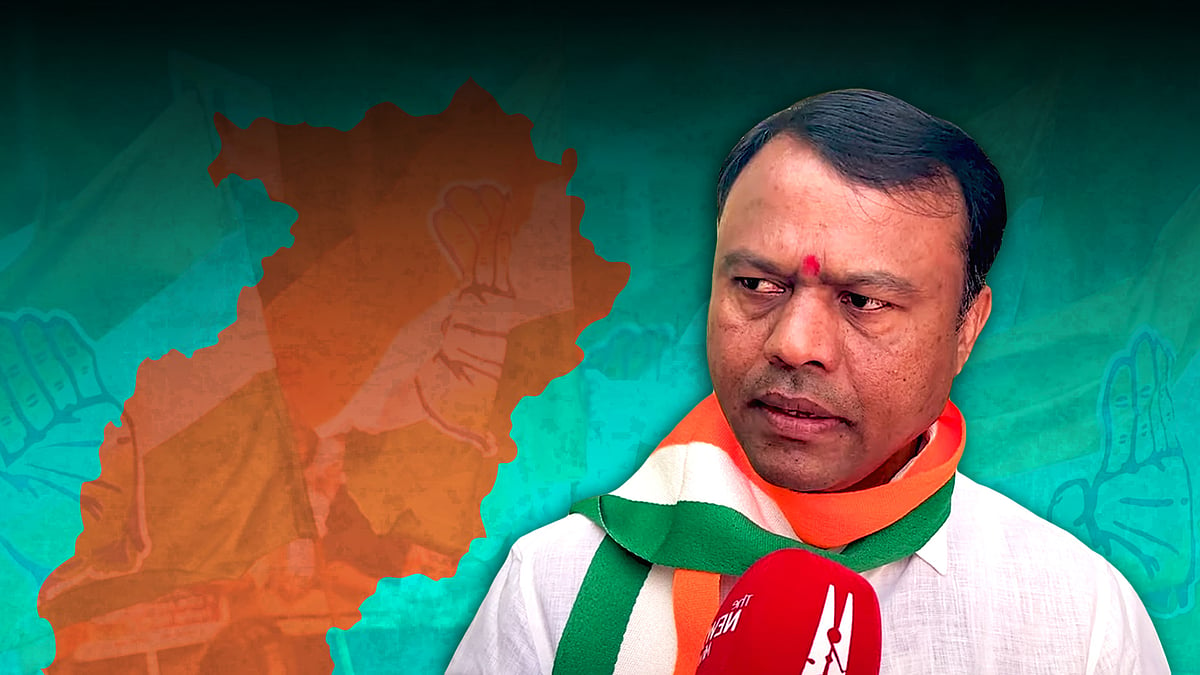

From Kashmir to conversions, with Himanta in Chhattisgarh’s ‘jinxed’ constituency ‘Will win over 75 seats’: Cong Chhattisgarh president on Adivasi CM, Maoism, corruption

‘Will win over 75 seats’: Cong Chhattisgarh president on Adivasi CM, Maoism, corruption