From surrender to law course: A Cong MLA’s journey from Maoist ranks to Telangana polls

Seethakka faces an uphill poll battle against the BRS candidate, who is the daughter of a late Maoist leader.

On a sunny November morning, Seethakka walked briskly on the narrow katcha road leading to Ramsingh Thanda, a Lambada hamlet in Pandikunta, Mulugu district. The Congress leader, who has twice represented Mulugu assembly and is hoping to win it again this time, was greeted warmly by locals as she appealed for votes.

It was in the same hamlet where Danasari Anasuya, popularly known as Seethakka, had taken cover from the police nearly three decades ago. The former Maoist, who was pregnant at the time, was eventually caught. But much has changed since then.

From commanding an armed militia in Narsampet and being a member of the CPI (Marxist-Leninist) Janshakti, Seethakka is now seeking votes and encouraging people to participate in the electoral process. And if the Congress is voted to power in Telangana, she hopes to become a minister – there is speculation that she is even in the race for the chief minister’s post.

Seethakka faces a challenge from 29-year-old Bade Nagajyothi, who is making her political debut on a BRS ticket and is the daughter of late Maoist leader Bade Nageshwara Rao and ex-Maoist Rajeshwari. She is also the chairperson of the Mulugu Zilla Praja Parishad.

Seethakka, on the other hand, is the youngest daughter of Saraiah and Sarakka, members of an Adivasi Gutti Koya family. Born and raised in Jaggannapeta in Mulugu, which borders Chhattisgarh, the young Seethakka was inspired by ‘Annas’ or Maoists. In the early 80s, Annas wielded significant influence and commanded respect, particularly from the Adivasis who were facing suppression from landlords, said Seethakka. It was not uncommon for Adivasis in the Mulugu region to join Maoist ranks – her brother Sambaiah, also a Maoist, was killed in an alleged encounter.

Seethakka completed her primary and secondary education at the Mulugu Government Girls Residential School. “We did not have enough means. So she had to study in a government school with a hostel facility,” her mother Sarakka said. After completing class 10, Seethakka joined the CPI (ML) Janashakti party in 1988 and dedicated her life to fighting against class and caste oppression. Recalling her childhood, her cousin Venkanna said, “From a young age, she was a rebel. It was not surprising when she went into the forest [to take up arms]. She would fight for quality food even during her hostel days.”

Danasari Anasuya was rechristened Seetha when she joined Maoist ranks – the name was deemed appropriate by other Maoists as her husband’s name was Ramu (Kunja Ramu). Ramu, who was her cousin and also a member of Janashakti, was one of the reasons behind her joining the far-Left CPI (ML) party. Even though the couple later parted ways, they were once considered the ideal match.

“She is one of the most committed leaders I have ever seen. She used to work very sincerely without expecting anything in return. She dedicated her life to the liberation of the people,” recalled Chaitanya Thummala, a former member of the cultural wing of Janashakti.

Besides singing and writing songs, Seethakka would spend a lot of time with children. “She was of a soft-hearted nature. I first saw her in the forest during a meeting when I was 21. She would mingle with everyone and had spectacular clarity, courage, and commitment.”

Seethakka gave away her son for adoption when he was just two months old. “It was probably the yearning for her own son that made her interact with kids. She was a very kind person. That’s what made me realise that she was a true revolutionary,” the Janashakti member recollected. “She would also have intellectual political debates with Veeranna,” Chaitanya said.

Giving up arms

In 1977, Seethakka gave up arms and surrendered before the court under the state’s amnesty programme. Why did a commander committed to the Maoist ideology leave the party?

According to her, it was the split within the Janashakti party that led to the abandonment of the armed movement.

The CPI-ML-Janashakti was formed in 1992, after seven organisations merged into a one-party organisation. The unity lasted for four years. In 1996, a year before Seethakka surrendered, a faction broke away and formed the CPI-ML Unity Initiative. Subsequently, many factions broke away, leading to a crisis. “Maroju Veeranna formed his own faction Communist Party of United States of India. Our numbers were already low and there were many divisions. It was a time of crisis and many people had left the party. Even I had to leave,” Seethakka said.

The Congress leader said she was disillusioned by the movement by then, and was critical of the party’s activities being restricted to the jungle. “I never thought that I would give up arms. There was no such thought, nor did I care for my family. Sacrifice was one of the tenets of working for the revolution.”

Her son Surya was four years old when she gave up arms and emerged from the underground. After serving three months in prison, Seethakka joined Yakshi, an NGO working for Adivasis in Hyderabad. “I earned Rs 2,500 in my first job,” she recollected.

While working at this NGO, Seethakka finished her law degree from Padala Rama Reddy Law College in Hyderabad, after which she began assisting a lawyer. “I took up law so that I could help my community who were being harassed by the police. Many were facing cases for their association with Maoists. I saw them struggle to fight these cases. Besides that, law is a dignified profession.”

Entry into politics

While working for Yakshi, Seethakka travelled extensively across the Adilabad and Srikakulam districts, which had sizable Adivasi populations. Yakshi worked with Adivasis, training them in research and understanding their communities. This exposure which offered her the chance to interact with over 30 Adivasi communities led her towards mainstream politics, said Nadempalli Madhusudhan, the executive secretary of Yakshi.

“She worked along with me for nearly two years. She was part of the leadership programme of Adivasis. She was trained to understand the necessities of the Forest Rights Act. She was introduced to academic research and was able to replace political rhetoric with a nuanced understanding of Adivasi issues. She was part of the campaign to educate people on the Forest Rights Act,” he said.

Seethakka was also part of the International Fund for Agricultural Development programme, which evaluated the funding of the Integrated Tribal Development Agency and its socio-economic impact on Adivasis. This programme meant that she travelled extensively to many Adivasi districts of undivided Andhra Pradesh. “During our trips to Adivasi areas, we would have serious discussions around the plight of Adivasis. This particular exposure made her choose mainstream politics,” Madhusudhan said.

During this stint, she got in touch with leaders of the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and showed an inclination to contest in the Assembly elections.

Even though Seethakka had moved away from her earlier years in politics, in 2003, she was faced with a dilemma when Maoists of the People’s War Group carried out a failed assassination attempt on former chief minister Chandrababu Naidu in Alipiri, Tirupati. “Since the beginning, I had a differing view when it came to killing people,” Seethakka said, condemning the actions of the Maoists. She said that Naidu had acknowledged the plight of Adivasis and provided them with education, primary healthcare, and employment.

In 2004, Seethakka contested from Mulugu constituency on a TDP ticket. However, she failed to woo the voters. “The people had their own reasons to reject me. Why would they trust someone new?”

In 2009, she emerged victorious and was elected to power. But she lost again in 2014, after Telangana achieved statehood and a TRS wave took over the state’s politics. In 2018, she resigned from the TDP and contested on a Congress ticket. Even though the TRS won 88 seats that year, it could not defeat Seethakka.

Seethakka recently finished her PhD at Osmania University, with research on the “social exclusion and deprivation of the Gotti Koya tribe”.

While Seethakka’s Covid relief work in remote areas was hailed by many on social media, her efforts during the recent floods in Warangal upset many leaders, including those from her own party. “All that she does is for publicity. She does some welfare activity and publicises it heavily using social media,” said a Congress leader.

But the two-time legislator is not offended by these observations. “I shared photos and videos of my relief activity during Covid-19 in order to seek help from others. I was helping, but I am not an entire administration. Critics will fault everything.”

For Sarakka, her daughter may have given up arms and taken up mainstream politics, but there has hardly been any change. “There is hardly any time that she dedicates for family.”

This report has been published as part of the joint NL-TNM Election Fund and is supported by hundreds of readers. Click here to power our ground reports.

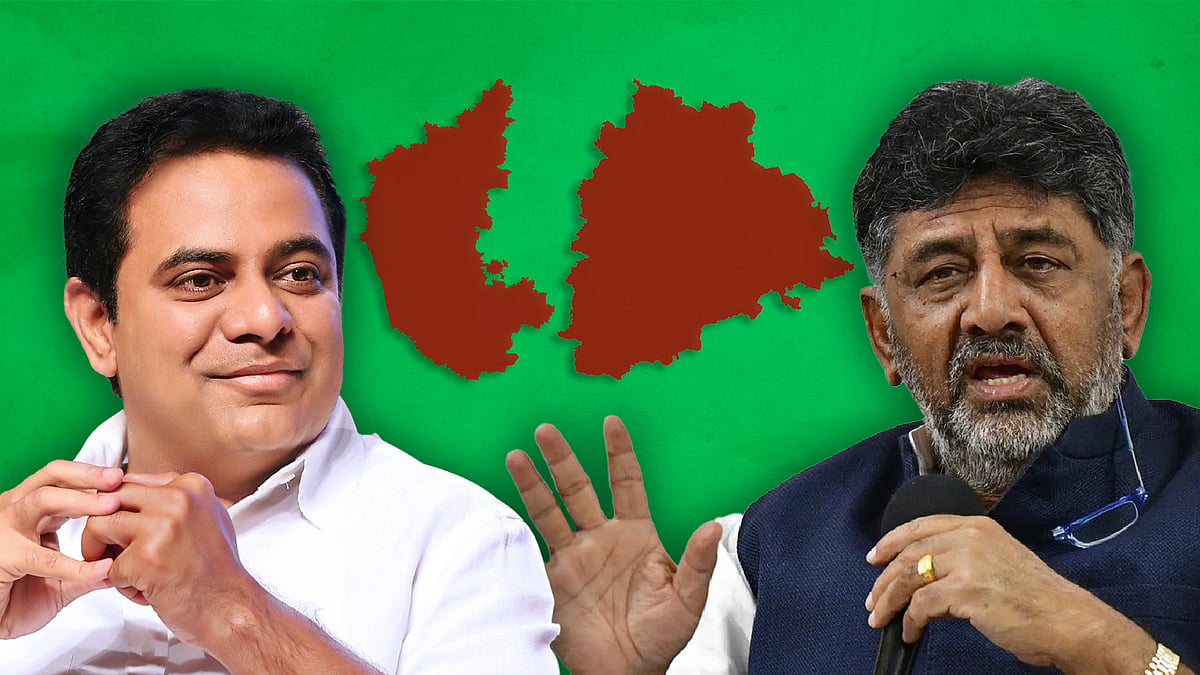

As Cong bids for Telangana, BRS warns voters of Karnataka ploy, ‘conspiracy’ against state

As Cong bids for Telangana, BRS warns voters of Karnataka ploy, ‘conspiracy’ against state