Reporter’s diary: Anguish and rage in the abandoned state of Manipur

My trip to Manipur was five months ago. But little has changed since then.

On July 23, the morning flight from Delhi to Imphal was packed with security personnel – perhaps the first sign for the uninitiated that all was not well in Manipur.

Huddled in the aircraft with my colleague Priyali, we looked out the window as we landed in the valley. “Stunning!” I thought, looking at faraway hills that kissed the sky.

It was my first trip to the Northeast but I had little time to spend on nature’s beauty. After my colleague Prateek joined us from Pune, we hit the road. The streets were cluttered with security barricades and devoid of people, except for the odd car or bike. Manipur, after all, was under curfew, torn apart since May 3 by violent animosity between the Meiteis and Kuki-Zos. Two communities who, as someone once wrote, had always lived together – but separately.

We quickly learned that geographical lines had been drawn by both civilians and security forces. The Meiteis lived in the valley, the Kuki-Zos in the hills. Neither could enter each other’s territory, dead or alive. This separateness manifested in barricades, closed shops, burnt and bulldozed settlements, children not at school but in relief camps.

There were other, more tragic displays. In the worst bout of violence in recent memory here, children and women were not spared.

At Hotel Imphal, we planned to grab a quick meal but the food was a long time coming. We learned they were short-staffed. “Kukis have left after the violence,” one staff member told me. I would soon find out that most restaurants, which predominantly employed Kuki-Zo people, were closed.

From the valley

On July 24, we drove to the gunfight site of Phougakchou and other areas in Bishnupur district. Vehicle after vehicle disgorged youths in army fatigues, their faces covered. Conventional and automatic arms were aplenty.

As Prateek and I walked towards the frontline, two mortars exploded. Smoke leapt from a distant village. Here was where Meitei teachers, former armymen and students were fighting for “their land”. The Kukis, we were told, had the altitudinal advantage. Central forces watched the gunfight from the main road while army vehicles were held back by Meira Paibis or “torch bearers”, a group of activist women who are a constant feature in the valley for their presence at protests and rallies. The police walked toe to toe with armed “volunteers”.

The sheer volume of guns overwhelmed me. The Biren Singh government has done little – nothing, even – to recover arms and ammunition looted from government armouries. By the end of October, only 25 percent of arms had been recovered so far.

But a war needs money. Meiteis turned to common folks and business men in the Bazaar area of Imphal. Those who dragged their feet to contribute were threatened. Extortion was an open secret and everyone seemed nervous.

In the middle of Imphal city, I came across small barricades formed by corroded oil drums. These “checkposts” were manned by four or five Meira Paibis, who would stop commuters and collect “voluntary” contributions. Our driver slipped Rs 50 into a donation box.

Relief camps were a regular feature along the road and inside the alleys of the valley area. Help poured in from civil society groups. But it wasn’t enough for a displaced population that had lost everything. A Kuki-Zo government teacher, who had spent 30 years of his life in the hills, sobbed to me. “My home and childhood memories are in the hills,” he said.

To the hills

On August 2, we moved from Imphal to Churachandpur, located in the hills. We had to cross checkposts manned by central forces near Kangvai. There were levelled houses and ruined tin houses on either side.

At the final checkpost, an armoured casspir of the army was just before us, stopped and questioned. Then it was our turn. We presented our ID cards and were allowed to enter Churachandpur. As we departed, we saw the casspir being searched by a large group of women wearing black. One of them said, “We have information that the army is sneaking in police commandos.” There were arguments on whether the casspir could enter or not.

In Manipur, there’s deep resistance to the entry of central forces into key areas. The hills and valley are deeply homogenised. Our driver, a Meitei Pangal, who took us to Churachandpur was looked upon with suspicion for his facial features. “He does not look like a Pangal,” someone said.

Kuki-Zo tribes reject the name Churachandpur, choosing the word Lamka instead – and across Churachandpur, I saw walls emblazoned with Lamka. Other walls carried the words “separate administration”. I now pick through the memories – a group of four-wheelers carrying armed youth rushing to the frontlines in the border areas of Churachandpur-Bishnupur, intact bunkers (which the government said were destroyed) along German road, a college student at Khousabung who showed me the single-barrel gun he would use to “protect the land from Meiteis”.

As we packed up to leave Churachandpur, we were caught in heavy cross-fire at P Geljang village. We sheltered behind sandbags with “volunteers”. Jokes were cracked. Every now and then, militants from hardcore groups under suspension of operations routinely arrived to reinforce volunteers

An army officer showed me letters from the central forces to the state and union governments, sent before the violence broke out. The letters alleged Kuki militant groups were not complying with the suspension of operations agreement, a ceasefire treaty signed by two dozen Kuki militant groups with the state and central governments in 2008 for a ceasefire. A confidential report from 2021 said cadres from these groups were not staying in designated camps as per the pact.

“We had alerted the government long ago but they did not act on these inputs,” the officer said.

Shutdowns, silence, status quo

Manipur’s internet was completely or partially suspended for 200 days from May 3 – one of the longest shutdowns in India. It turned people’s lives upside down, and it still continues. Everyone I spoke to – professionals, businesspeople, students – decried the blackout.

The press was left bruised too. Misinformation and disinformation were landmines that journalists in Manipur had to navigate. The internet is now a necessary tool for modern journalism, so we had to rely on a government institute with an internet connection in Imphal to file our reports. There, we’d meet students who turned up everyday to go online. In the hills, some youths were forced to travel several kilometres just to stay connected.

The blackout also posed a challenge for journalists to verify facts. Newspapers on both sides were partisan, we were told by journalists in the valley and the hills. “Unless a journalist visits both sides, her story will lack objectivity,” one of them said. Meitei journalists and Kuki-Zo journalists could not visit areas not dominated by their communities. Besides accessibility, journalists avoided critical reporting, fearing for their safety.

Before I arrived in Manipur, I had worried about safety too, about encountering armed mobs. I was scarred by traumatic experiences in Delhi during the 2020 riots. But at no point did my colleagues and I face hostility in Manipur, either in the valley or in the hills.

There was one question I asked many of the people I met – “What can bring peace to Manipur?” The answers were varied but offered up a couple of solutions. One, a free hand for central forces to disarm militants and radical groups. Two, active intervention by the central government.

But it took Narendra Modi 79 days to speak about the violence. He’s still not visited Manipur. In July, many in the valley looked forward to his Mann Ki Baat, hoping he’d touch on topics close to them – but he didn’t. They were anguished.

Meanwhile, bodies decomposed in mortuaries. Students left their campuses. An estimated 52,628 displaced people crammed into 337 relief camps. Over 180 people died. And Modi did not grant an audience to aggrieved MLAs from Manipur.

My trip to Manipur was five months ago. But little has changed since then.

Ground reports like these take time and resources. Help us tell more stories that are in public interest. Subscribe today.

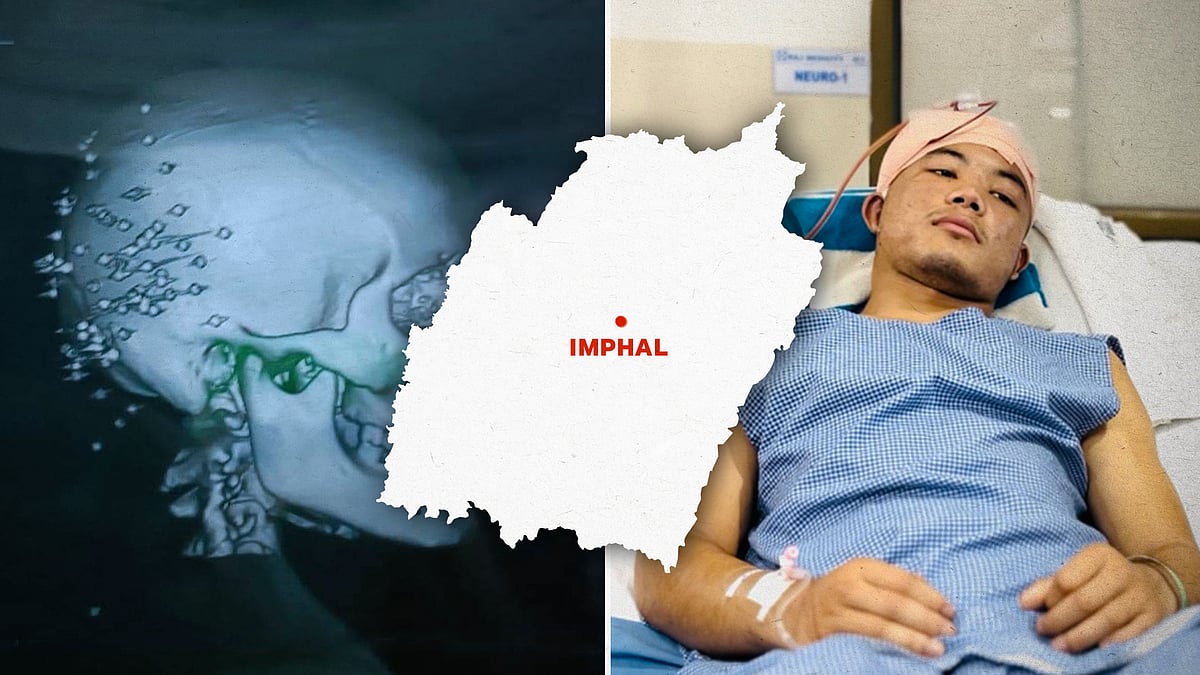

‘There were 90 pellets in his shoulder’: In Manipur, central forces accused of targeting school students

‘There were 90 pellets in his shoulder’: In Manipur, central forces accused of targeting school students ‘Can still feel the blows...Imphal murdered my family’: Manipur violence survivor recalls escape

‘Can still feel the blows...Imphal murdered my family’: Manipur violence survivor recalls escape