Between faith and livelihood: Days before Ram temple inauguration, fear and excitement in Ayodhya

Locals are pleased with the temple’s construction, but discontent brews over Ayodhya’s transformation wrecking homes and livelihoods.

In the early hours of 2024, Ayodhya town resembles a gigantic movie set from a modern-day Bollywood mythological saga.

Bulldozers, excavators, and drilling machines whir at every corner. Thousands of labourers work through the night, building pavements, mounting customised sun-emblem streetlights, and adding last-minute touches to outer facades.

The buildings along the three main roads – renamed Ram Path, Bhakti Path, and Ram Janmabhoomi Path for an added dash of deviation – are adorned with saffron paint, Nagara-style arches, and Ramayana-inspired motifs featuring Hanuman, bow and arrow, and mace.

The animated layout, developed at a staggering cost of Rs 30,000 crore, reimagines the mythical kingdom of Ayodhya during the reign of Lord Ram. It forms the dramatic backdrop for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s epic inaugural ceremony of the Ram temple on January 22 and the launch of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s 2024 election campaign.

The actual construction of the main temple, where the consecration ceremony will be conducted for a new idol of five-year-old Ram, is far from over and likely to be completed only by 2025. But the buzz around its manifestation and Ayodhya’s impending transformation is infectious. Buoyed by the BJP’s fulfilment of a core ideological promise, thousands of Ram devotees have been flocking daily to the temple town.

For Ayodhya’s residents, who’ve witnessed the pain and politics of living close to Ram Janmabhoomi over the last seven decades, the long-awaited development is more of a bane than a blessing. The road widening and beautification being carried out to enhance the limited infrastructure has unleashed a trail of destruction that’s wrecked their homes and livelihoods.

Stuck in a time warp

Sitting on the unlevelled mud floor of her semi-broken home, kitchenware and clothing strewn all around her, Manju Modanwal glumly says the Ram temple’s construction is a “good thing”.

“Sabse badi samasya samapt hogayi, aur ka?” she says in Awadhi, her expression deadpan. (The biggest problem is over, what else is there?)

The temple will finally free Ayodhya from the grip of the mandir-masjid conflict. Residents will no longer have to bear the cost of communal tensions, curfews, and constant police bandobast. Manju, hailing from the Halwai community, hopes her children, at least, will have a better future, both economically and socially, even as she struggles to sustain her family in the remnants of the house-cum-shop located at Ram Path.

When the temple’s construction got underway, she did not anticipate the sacrifices her family and others in the town would be forced to make. In April, the front portion of their home, where they run a chaat bhandaar, was demolished as part of a road-widening project. Over 4,000 residential and commercial structures, including several ancient temples and mosques, were razed to widen the 13-km road, which connects Shahadatganj in Faizabad to Naya Ghat, by 20 metres.

“This is the first time we are seeing any kind of development,” says Manju’s college-going daughter Rani. “All these years, no government did anything for this town. Everything new you see around has been developed in the last two years.”

The decades of legal and communal conflict over the right to construct the temple left Ayodhya woefully underdeveloped in terms of basic infrastructure and public amenities. Large parts of the town are dotted with narrow lanes, crumbling courtyards, ancient temples, mosques and minarets, and brick and sand houses, like a time frozen in a dusty frame.

The three-km precinct surrounding Hanumangarhi and the Ram Janmabhoomi temple is filled with temples, tiny shops, and hawkers selling puja paraphernalia, garlands, plastic toys, jewellery, and spiritual books. There are no big, fancy shops or restaurants. Visitors who mostly arrive on day trips are dependent on corner shops for snacks and chai, and dhabas for meals.

Which is why Rani is excited about the rapid pace of development, bringing the frills of a modern city to the tranquil temple town: a new airport, wifi zones, a Ramayana theme park, and recreational activities at the ghats.

“From one perspective, all this change is good,” says Rani, “and from another, it is also destructive.”

The Modanwal family received compensation of Rs 1.5 lakh, but it wasn’t enough to cover the cost of a new floor or wall plaster, leaving the house decrepit.

Small shopkeepers and businesses have paid a heavy price for the road expansion projects, says Nandu Kumar Gupta, president of the Ayodhya Udyog Vyapar Mandal trade union. “It should have been planned keeping in mind the interests and welfare of the native population. Instead, we have been harassed and threatened and paid a penury in compensation.”

Gupta, a member of the Samajwadi Party, alleges authorities disconnected the power supply to his residence and seized equipment from his shop after he led protests against the demolition. “Common people are aggrieved, but no one dares to raise a voice. There is fear among people that if they raise their voice against the development, they will face a police case or, worse, a bulldozer will arrive at their house.”

‘Unlimited’ opportunities, little choice

Prior to 2019, tourism footfall in Ayodhya was largely restricted to local pilgrims from the neighbouring towns and villages. They would visit for popular fairs and festivals like Ram Navmi, Kartik Snan, Rath Yatra and Ram Vivah, spending frugally, residing in free dharamshalas, and feeding on prasad bhog distributed at temples.

Then came the Supreme Court verdict of 2019, which ordered the disputed land be handed over to Hindu groups to build the Ram temple. With the decks cleared for the temple’s construction, Ayodhya began to witness never-before-seen changes in land investment and commercial avenues.

Local resident Ritesh Awasthi says he opened two hotels in a kilometre radius of the Ram Janmabhoomi in the last three years, as “unlimited opportunities” opened up in the hospitality and real estate sectors.

“There’s good business for everyone. Even those who apply Jai Shri Ram tika on the foreheads of devotees are earning Rs 1,000 daily,” he says, adding that the development has, for the first time, brought a sea change in the attitudes of Ayodhyawasis, whose business ideas were limited to “selling sindoor, bindi, and besan ladoo”.

The Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust, set up by the central government to construct and manage the Ram temple, plans to bring millions of pilgrims from India and abroad. Vishal Singh, chairman of the Ayodhya Development Authority, says in the months to come, authorities expect the number of tourists to swell to over three lakh per day, higher than the entire city’s current population.

To accommodate the massive influx of tourists, the trust is working with the UP government, Ayodhya district authorities, and the town’s municipal corporation to develop new infrastructure and plan arrangements.

This includes land allotment for hotels, residential projects, a series of initiatives across civil works, transport, upgradation of the existing railway station, luxury tent cities, and homestays.

“We have worked on every aspect of catering to the pilgrims,” says Singh. “We will keep increasing the capacity of our public amenities and infrastructure as we move along.” The focus is on “inclusive development” whereby locals can also benefit from the economic opportunities.

Purshottam Jha, a shopkeeper, agrees that Ayodhya’s locals profit from the expanded tourist outflow since the Modi and Yogi government at the centre and in UP heavily began to promote Hindutva.

“But now we are left with no alternative,” he says. “Nor do we believe any arrangements will be made to accommodate thousands who lost their houses and livelihoods in the expansion project.”

Jha owned a shop, approximately 10x12 feet, at Ram Gulela market close to the Amawa Ram mandir, adjoining Ram Lalla’s makeshift temple. It sold puja items, brass metal utensils, and bangles, but was demolished last November. He received compensation of around Rs 1 lakh and was allotted a shop at a new commercial centre near the Tedhi Bazar chauraha, a km away from the main temple complex. But, as he points out, no tourist would be inclined to shop for small puja items so far from the temple.

Additionally, the cost of the shop – Rs 27 lakh for a 30-year lease – is out of his budget. “There’s no way we can afford to take his shop, even if we take a bank loan of Rs 8 lakh,” he says. “Hum toh abhi Ram Bharose chal rahe hai.” (We are living at the mercy of Lord Ram.)

Versions of this story are repeated across Ayodhya. Several commercial and residential structures are on the verge of being cleared away for the mega-development projects unfolding phase-wise. Away from the temple’s precinct, municipal authorities on December 20 informed shopkeepers and families at Naya Ghat to vacate the premises.

Babu Chand Gupta, who received the warning, says small traders and merchants – who have traditionally set up shops catering to the pilgrim tourists around temples and ghats – are left with no safe alternatives to earn a livelihood.

“There is no land left in the main town of Ayodhya for common people. Government is acquiring all the land and compensating affected people with a token amount,” he says. “Where are we supposed to go?”

What about Muslim welfare ?

The same question rings true for the district’s 3.5 lakh-odd Muslims, who have lived side by side with their Hindu neighbours. The community has suffered the most horrors of communal violence and polarisation emerging from the dispute over the Babri Masjid land.

“We are happy about the temple’s construction. The conflict has been put to rest and we want to move forward,” says Azam Qadri, president of the Sunni Central Waqf Board.

The ghosts of Babri are hard to bury. Muslim families still hold the memories of karsevaks tearing down the mosque’s domes. Eighteen Muslims were killed in the ensuing riots, followed by the arson and looting of Muslim properties.

Mohammad Umar, a resident of Kotwali area, fears a repeat of the events of December 1992 as scores of Hindu pilgrims will begin to descend in Ayodhya from next year.

“It happened to me then and it can happen again,” he says, explaining that his house was identified and burned down by a raging mob three decades ago. After painstakingly rebuilding his life and home, Umar suffered another setback last December as he lost part of his house and shop to a demolition drive for a road-widening project.

He now lives among the dead in a nearby kabristan, cemetery, where he’s constructed a temporary room for his family of four. In the little space of his former home, he’s opened a hardware shop with a nondescript name to prevent it from being targeted by miscreants.

“Muslims have limited business options here,” says Umar. “Tourists don’t buy from Muslim-named shops and we can’t open restaurants or chai shops as Hindus won’t eat food from our hands. We have no choice but to do business discreetly.”

Umar and other Muslims attest to Ayodhya’s model of aman and ekta, peace and harmony, which has fostered a template for peaceful existence with their Hindu neighbours.

“It is always the outsiders who have stirred conflict and turned us against each other,” says Qadri. “Even if one or two elements are looking to create some kind of trouble by targeting Muslims, it can vitiate the atmosphere.”

But last year, the police arrested a group of seven Hindu men, all locals from Ayodhya district, for throwing alleged pork, abusive letters, and torn pieces of Islamic text at several mosques – Masjid Kashmiri Mohalla, Tatshah Mosque, Ghosiyana Ramnagar Masjid, Idgah Civil Line Mosque and Gulab Shah Dargah – in Ayodhya.

Muslim families say they have made compromises to avoid tension with Hindu neighbours. Eid and other religious celebrations are subdued and police permissions for festive gatherings are mandatory. Last year, Muslim leaders reportedly changed the timing of the Muharram procession to avoid its clash with a Hindu festival. Locals say Muslims can’t sell meat or meat dishes in the main temple town.

These changes have driven the minority community to the shores of invisibility, threatening their existence, religion and way of life. Qadri accuses Hindu fundamentalists and certain pandits of trying to take control of Muslim land.

“Land mafia are threatening to seize our religious properties. Our ancient mazars, tombs, small mosques, and even graveyards are not safe. The government is spending thousands of crores for a new temple but it has no money to uplift Islamic heritage,” Qadri says, adding that the community’s appeal to the district administration to protect these properties and release funds for their maintenance has evoked no response. “Does Ayodhya belong only to Hindus?”

Multiculturalism is Ayodhya’s heritage

Historically, Ayodhya has been the centre of influence for Hinduism as well as Islam, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. Hindu temples aside, there are over 100 mosques, five Jain temples as well as gurdwaras and ancient Buddhist sites excavated by the Archaeological Survey of India.

Sampoornand Bajpai, a retired schoolteacher and social worker, rues the loss of Ayodhya’s multiculturalism. “It has turned into a commercial project for big corporations to make money and for the government to earn votes.”

The current development, encompassing big statues and widened roads, is not the development locals want, he says. “All this organisation is being done for the benefit of tourists and visitors, whereas common people’s issues on basic infrastructure are being ignored.”

He gives the example of his own residential colony in Begumpura that has had no running water for the last four months. He also says there are no specialised doctors or good hospitals in the area to treat cancer and cardiac issues, forcing him to travel to Lucknow for bypass surgery.

“The BJP government wants to showcase Ayodhya’s development for the 2024 elections and seek votes on the Ram Mandir model,” he says. But Ayodhya’s real significance for the BJP, Bajpai warns, is reflected in its stand banning the local population from attending the inaugural ceremony. “They are making a temple in our city but don’t want the native residents, the mool Ayodhyawasi who have the first rights on Lord Ram, to attend its opening. We have been asked to stay at home.”

Photos by Shweta Desai.

This report is part of our NL Sena project on Ayodhya 2.0. Contribute now.

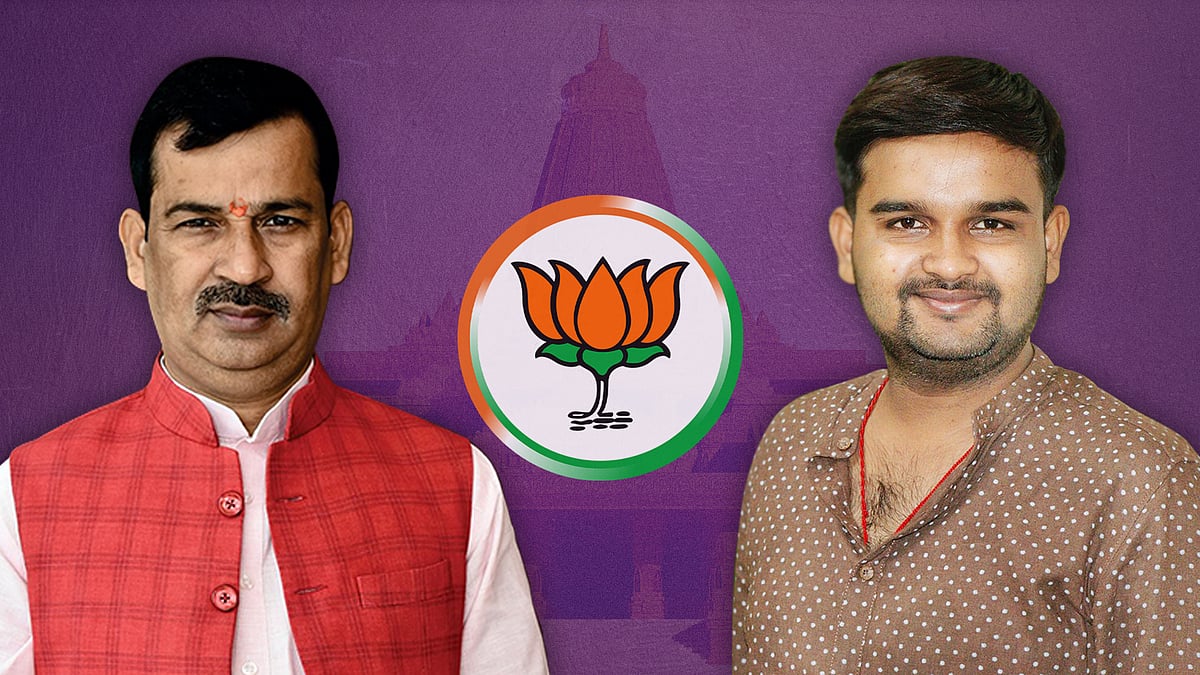

Exclusive: Ayodhya BJP mayor’s nephew bought land for 20 lakh, sold it to Ram temple trust for 2.5 crore

Exclusive: Ayodhya BJP mayor’s nephew bought land for 20 lakh, sold it to Ram temple trust for 2.5 crore What happens when Ram anchors a TV debate about Mandir?

What happens when Ram anchors a TV debate about Mandir?