Coverage of Ambani ‘pre-wedding’ tells you everything that’s wrong with the media today

The decline and fall of journalism continues, with many journalists just treading water to survive.

Last week, I spoke to some students at a Mumbai college. They were in their second-year of a three-year degree course in media studies. I asked them how many of them wanted to be journalists. In a class of around 35, only one young woman raised her hand.

Some others explained that in the first year, more of them had considered journalism as a career. But over time, they had concluded that there was no future in it.

If 19-year-olds in a Mumbai college think there is no future in journalism, what is the future of journalism in this country?

The question came even more sharply into focus last week when a journalist with more than 20 years of experience, working with a national newspaper in Mumbai, literally died on the job. He was not in a conflict zone. He was in his office in central Mumbai.

His unexpected death led to considerable churning amongst journalists in Mumbai and elsewhere. It raised several questions that concern not just journalists but the media. It illustrated the insecurity and stress that journalists live with even when performing routine functions.

The death of this journalist also brought focus again on the state of the Indian media.

Take, for instance, coverage of events leading up to the “pre-wedding” (not sure what that means) of Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant in Jamnagar, and the event itself.

In the days before this “pre-wedding”, print media and television news carried glowing reports about Vantara, an elephant sanctuary set up by the Ambani scion. If you read the print reports, you will wonder whether they are reprints of a press release sent out by the Ambani communications team. There’s little variation. They are factual, yes, but there isn’t one critical question. From these reports, it is evident that the journalists went on a paid junket.

Yet, of all the English newspapers I looked at, only one – Indian Express – carried this disclaimer: “The correspondent was in Jamnagar at the invitation of Reliance Foundation.” And one newspaper, The Hindu, chose not to send a reporter even though it also received an invitation.

Print coverage, however, was restrained compared to the cringe-worthy report by prominent India Today anchor Rahul Kanwal. Watch his report, especially from 20.45 minutes onwards where you see him exulting over the taste of the food prepared for the elephants! It’s entertaining, but it is not journalism.

All this animal talk was only a precursor to the actual event, that stretched over three days with the broadcast media giving a blow-by-blow account of the parade of national and international celebrities that hot-footed it to Jamnagar, a city in Gujarat with an Indian Air Force base that accommodates a limited number of domestic flights.

Most newspapers and channels failed to ask the obvious question: How will all these guests make their way to Jamnagar if there is no international airport? Jagriti Chandra of The Hindu filed this story. She found that, in no time, small Jamnagar airport was converted to an international airport for 10 days. All permissions were cleared. After all, what could be more important than the “pre-wedding” of the son of one of India’s richest men? Unfortunately, The Hindu buried the story on an inside page although it deserved to be on the front page.

Why bother to comment on the media’s predictable coverage of this over-the-top “pre-wedding”, you might ask? Because it forces us to acknowledge, yet again, that mainstream media in India has moved a very long way from what was once considered “journalism”.

I have placed the word within inverted commas for a reason. Because given the nature of politics in this country, the open nexus between politics and business, and the concentration of ownership of the media in the hands of big business, we must ask how long journalism of the kind that existed even a decade back will survive.

The media has been transformed over time to a product that must be sold. Once that is accepted, there is little room to discuss why this product is any different from any other: a bar of soap or a packet of chips. All need sales pitches. The more they sell, the more the business prospers.The more people read, listen or watch your “product”, the more advertising will come your way.

But what about the producers of this product, the journalists? Where do they stand in all this? Where is the idea of what journalism was all about? Is it even relevant today in this new scenario?

There was a time, not too long ago, when journalists found secure employment. Under the Working Journalists’ Act, journalists’ salaries were fixed based on the circulation of newspapers and the designation of the journalist. They also got the kind of benefits people working in other formal sector companies received such as a provident fund, gratuity, bonus, medical allowance, etc.

Most importantly, they could not be sacked arbitrarily. There was a process to be followed. And there were unions that could stand by journalists. Although salaries were low, journalists had what we would jokingly call STD (security till death). Now, this has literally become ISD (insecurity till death).

Today, most journalists are on contract. They can be laid off without notice or explanation. During the Covid pandemic, many media houses laid off journalists and other staff. Some publications closed altogether. The unemployed then joined the growing number of independent or freelance journalists desperately looking for assignments for which they were paid a pittance, not enough if you had a family, or the inevitable debts that piled up.

Many journalists stepped out of journalism altogether and joined public relations companies or non-profits. Even if their hearts were in journalism and they loved what they did, they simply had no choice. Those who hung on and continued to go from one insecure job to another became victims of stress-related diseases.

Adding to these other stress factors are the conditions at work. Everyone is under pressure. Newspapers must show sales to attract advertising. And it is only advertising that covers the costs of not just paper and printing, but also salaries of journalists.

Increasingly advertising of the kind newspapers attracted, even the smaller ones, a decade ago, has shifted to broadcast, and now to digital. This means print media is scrambling, with only the largest in each language being able to sweep up most of the decreasing basket of advertising. And government advertising, from central and state governments, has grown exponentially, and with it another kind of pressure on print media.

The pressure to produce exclusives, to beat the competition, has increased manifold on journalists. In the past, print journalists did a story, sent it to the desk, and occasionally phoned in an update until closing time. Today, journalism is a 24-hour job. With digital, there is no closing time. Every page is open for news and updates.

Additionally, to keep up with the competition, even legacy print media now has podcasts and videos. The same set of journalists who write often have to take on these additional tasks. Yet, even as the nature of their work has changed, their jobs are not secure.

Those with some kind of financial backing have the choice of quitting and trying to find another job. But most journalists cannot give up a job in hand just because they have a demanding, or even abusive, boss. And the work is stressful – they just have to buckle down and do it.

Ultimately, all this affects the quality of journalism. Why would anyone break their heads to come up with an exclusive if they are not sure their paper will use it? And even if it is published, they might not be rewarded for it. You can get by doing the routine stuff, and that itself is a lot when the overall staff strength has been pruned. So, the majority would just tread water, continue with the minimum, stay under the radar, and collect their salaries at the end of the month.

Despite this, a handful of journalists in mainstream media still manage to write compelling, well-researched stories. Their work stands out and must be recognised. But we also need to shine a torch into the conditions under which they work. The death of the Mumbai journalist has triggered a much-needed conversation on the newsroom.

If you’re reading this story, you’re not seeing a single advertisement. That’s because Newslaundry powers ad-free journalism that’s truly in public interest. Support our work and subscribe today.

General elections are around the corner, and Newslaundry and The News Minute have ambitious plans. Click here to support us.

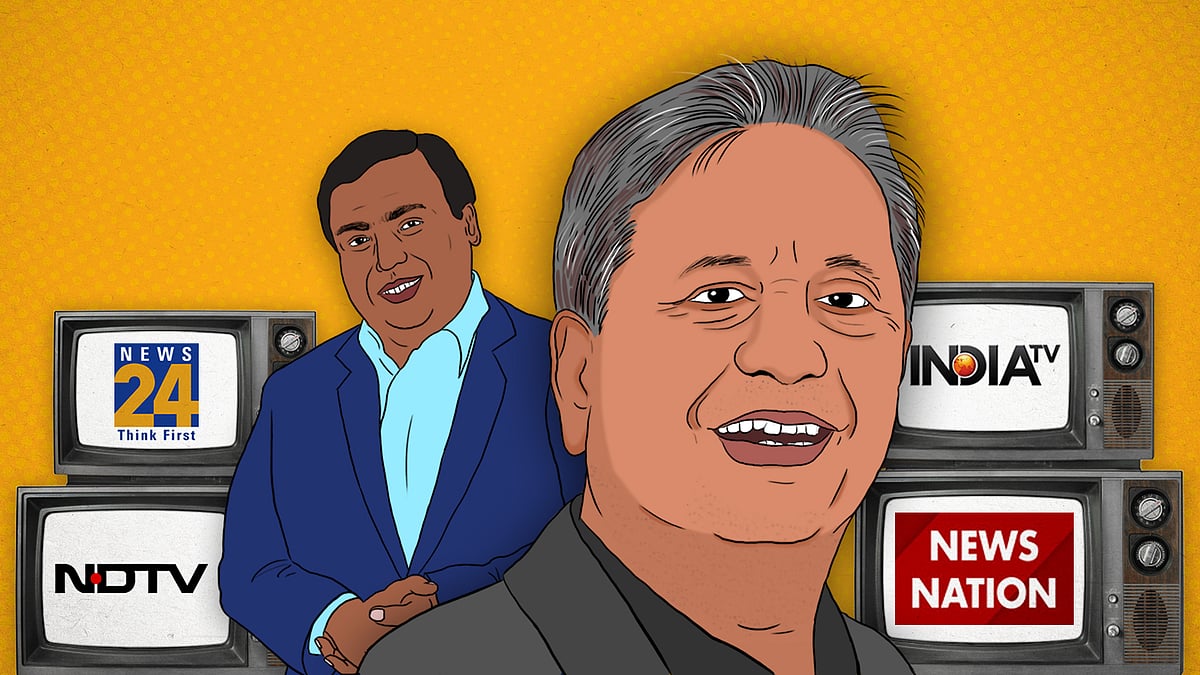

Meet the man who sold Ambani's NDTV stake to Adani

Meet the man who sold Ambani's NDTV stake to Adani