How Stan Swamy spent his last months in jail

Jail authorities were reluctant to provide Swamy with basic amenities, and did not have the medical infrastructure required to treat him.

“One day at a time, sweet Jesus. That’s all I’m asking of you. Just give me the strength to do every day, what I have to do.”

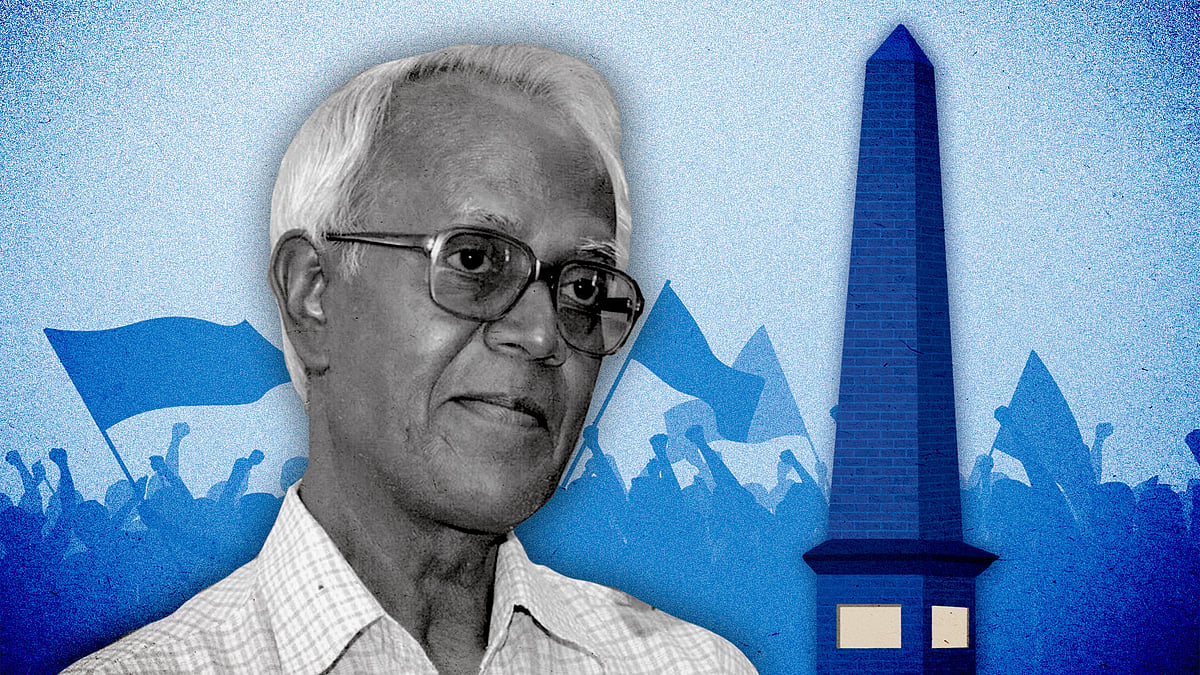

This hymn was sung by activist Arun Ferreira for Father Stan Swamy at Taloja jail, during their time together behind bars. Swamy, 84, would often ask Ferreira, his fellow accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, about the status of his bail. To cheer him up, Ferreira would sing these words to him.

Bail was something Swamy spoke about often, even when he was severely ill. He wanted to be surrounded by his own people in his final days, but he never got the chance. The tribal activist from Jharkhand died at Mumbai’s Holy Family Hospital on July 5. At the time of his death, he was still in custody.

Swamy was arrested on October 8 last year by the National Investigation Agency. His lawyers and family members of his co-accused repeatedly told the courts and the media about the inadequacy of his healthcare in prison.

Swamy had impaired hearing in both ears, had undergone two hernia operations, and had lumbar spondylosis. He had Parkinson’s disease and suffered tremors in both hands. His fellow inmates had to help him with tasks like bathing, eating and dressing himself, and he had frequent episodes of memory loss. He also tested positive for Covid on May 30.

Yet it took the NIA and jail authorities 50 days to agree to provide him with a straw and sipper.

Newslaundry parsed a number of court documents, orders and a letter from Father Joseph Xavier to Maharashtra home minister Dilip Walse Patil to piece together Swamy’s last days. At every turn, jail authorities under the supervision of former jail superintendent Kaustubh Kurlekar were reluctant to provide him with basic amenities.

Kurlekar was transferred from his post as superintendent last week.

A document notes that Swamy’s request for a full-sleeve sweater, a blanket, and two pairs of socks were denied. His friends tried to hand them over to him but were stopped at the gates of Taloja jail.

Swamy himself summed up his condition during a medical bail hearing on May 21. “Eight months and my health and bodily functions have severely deteriorated...Before I was lodged in Taloja prison, my body was functional,” he told the court. “I was able to walk, eat, bathe and write letters by myself...I am requesting you to consider why and how this deterioration of myself happened.”

He refused the court’s suggestion that he be moved to Mumbai’s JJ Hospital, saying he would “possibly die very shortly”. When he agreed to undergo treatment at Holy Family Hospital, the NIA and jail authorities opposed the idea of him being shifted to a “hospital of his choice”, since it would “set the wrong precedent”. Swamy was finally admitted on May 29.

‘I have no access to an MBBS doctor’

Swamy applied for bail three times during his incarceration. He also approached the court once to appeal against the rejection of his bail. All his petitions were denied. When the news of his death was made public, the Bombay High Court was in the process of hearing his bail petition.

When he applied for bail on medical grounds in October, February and April, the NIA pushed back. For instance, Vikram Khalate, superintendent of police, NIA, submitted an affidavit in the Bombay High Court on May 18 that disputed Swamy’s medical reports. The reports diagnosing Swamy with Parkinson’s and lumbar spondylosis were almost all over a year old, Khalate claimed, and therefore could not be considered as proof of existing conditions.

Subsequently, on May 19, a five-member medical committee was constituted on the court’s direction to examine his health. The committee noted “tremors in both upper limbs”, “sluggish reflexes in lower limbs”, “imbalance of gait”, “mild age-related lumbosacral degeneration”, “moderately severe” hearing loss in the right ear, and “severe” hearing loss in the left ear.

The committee recommended that Swamy “be provided with physical assistance, physical support in the form of walking stick, wheelchair as per requirement”.

At several court hearings, the NIA and jail authorities said Taloja jail has adequate medical facilities to treat sick patients. However, the prison does not have MBBS doctors on staff; it has three ayurvedic doctors to treat 3,251 inmates. This violates Maharashtra’s prison rules, which demands that every jail have five medical officers of the rank of assistant civil surgeon, three staff nurses, two pharmacists, three nursing attendants, two lab technicians, and two psychologists.

On May 17, Swamy’s friend and fellow Jesuit, Father Joseph Xavier, wrote to the Maharashtra home minister Dilip Walse Patil asking that Swamy be provided with medical attention. In his letter, he quoted Swamy as saying, “I feel weak and fragile. Only an ayurvedic doctor is available in Taloja. I have no access to an MBBS doctor.”

In Ranchi before he was arrested, Swamy’s neurologist prescribed him drugs like Ptempt, an antispasmodic medicine used in treatment of Parkinson’s, Ciplar and Mysoline. But in jail, he was given Ole-5 and Es-TRIM-10. Ole-5 is used to treat conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, neither of which Swamy was diagnosed with.

Kaustubh Kurlekar told Newslaundry, “As far as I know, medicines given to Swamy were based on the prescription allotted by his doctors from Jharkhand. We also have a visiting psychiatrist who treats patients of Parkinson’s. I am not a medical student so I cannot comment more about it.”

On ayurvedic doctors being assigned at the jail, he said, “Ayurvedic doctors are allowed to prescribe allopathic medicines as per the Practitioners Act and the order to appoint them comes directly from the department, so I cannot comment much on it. I am not an appointing authority so I cannot comment on the unavailability of MBBS doctors.”

Jenny Rowena, the wife of Delhi University Hany Babu who is also lodged in Taloja jail under the Bhima Koregaon case, told Newslaundry that Swamy’s death is an “institutional murder by the NIA, courts and prison system”.

“The arrest itself is invalid,” she said. “All these people have been booked on the basis of some papers and it has been clarified now that the documents were planted...After making a fake case, they have incarcerated them in the prison which has nothing. There is no proper drinking water, it is over-crowded. There are ayurvedic doctors giving allopathic medicines.”

Hany Babu himself was initially denied treatment for a serious eye infection, his family said, and was later not taken for a follow-up checkup. Like Swamy, he also tested positive for Covid. Babu is still in hospital.

Minal Gadling, the wife of Bhima Koregaon accused Surendra Gadling, said Swamy’s death was due to “sheer negligence on the part of jail authorities, NIA officials, and complete system”.

“If he had been given treatment at the right time, his life would have been saved,” she told Newslaundry. “But if someone in jail wants proper medical treatment in an outside hospital, he has to submit an application, then wait for the case to appear in court, and then wait for the argument. For an 84-year-old already having multiple ailments, such conditions delay the treatment.”

Allegations against Kurlekar

Two days after Swamy’s death, 10 of the accused in the Bhima Koregaon case held a hunger strike to protest Swamy’s “institutional murder” and demanded a judicial inquiry into his death. They released a statement blaming the NIA and Kaustubh Kurlekar for his death.

On February 26, 2021, Larsen Fartado, a junior lawyer of Rona Wilson, one of the accused, also filed a complaint against Kurlekar, stating that he had “harassed, threatened and insulted” him. The complaint was submitted to the additional chief secretary of the state home department and the DGP (prisons) of Maharashtra. Newslaundry accessed a copy of the complaint.

“I made visits to the Taloja jail to meet the co-accused for official and legal purposes,” Fartado told Newslaundry. “I visit to give them medicines, books and legal papers. I always followed jail procedures while visiting. Despite that, I have been harassed, threatened and insulted by Kurlekar on multiple occasions.”

For instance, Fartado said, Kurlekar “demanded unnecessary documents that are not even required to meet prisoners as per law”. “On one occasion, when I went to the jail to hand over some books, he insulted and threatened me. In front of other jail officials, he said, ‘Are you a lawyer or have you started a business to deliver books? Instead of bringing all these books, you should go to court and get bail for them.’”

Fartado said he tried to politely explain that prisoners have the right to read books. Kurlekar allegedly told him “people get weapons inside books and bring them to jail”. When Fartado said he never supplies books without checking them, Kurlekar allegedly said, “Are you going to teach us the law? Are you really a lawyer? Go to court and teach law over there. Should I teach you a lesson here?”

On July 3, the spouses of co-accused Vernon Gonsalves and Anand Teltumbde also filed a petition at the Bombay High Court seeking an inquiry into Kurlekar. Susan Abraham and Rama Teltumbde said Kurlekar had put restrictions on their spouses from writing letters to their families and lawyers.

When asked about this and Fartado’s complaint, Kurlekar told Newslaundry: “I cannot comment on putting restrictions on sending letters as the matter is in court. And why will I harass or threaten the lawyer of the accused? I don’t know why he made a complaint against me.”

Importantly, on June 7, Kurlekar approached Mumbai’s city and sessions court to transfer the male accused in the Bhima Koregaon case to different prisons. He filed an application stating that the accused were “defaming” the jail administration and filing “false complaints” through their family members. The court approved the application but the transfers have not happened yet.

Newslaundry reached out to Sunil Ramanand, the additional DGP (prisons), to ask him about administrative issues at Taloja jail. Ramanand did not respond to our queries.

Will mainstream media show the same attention to the Bhima Koregaon case as it did to Stan Swamy’s death?

Will mainstream media show the same attention to the Bhima Koregaon case as it did to Stan Swamy’s death? ‘My life is dedicated to the Adivasi people’: Stan Swamy after the 2019 raids on his house

‘My life is dedicated to the Adivasi people’: Stan Swamy after the 2019 raids on his house