‘We are watching’: How citizen-led initiatives safeguard democracy, electoral process

From chargesheets on the government to tracking hate speeches.

A string of violations of the model code of conduct during the 2019 Lok Sabha polls were reported to the election commission by the Indian Civil Liberties Union, a network of lawyers, students and activists. This time, the organisation is gearing to relaunch its #WeAreWatching project to create awareness about election rules among voters as India goes to polls beginning today.

Delhi-based advocate Anas Tanwir, 33, who founded the group in 2018, describes it as “a bunch of lawyers who deem the constitution worthy enough to fight for it.” The network has grown into a web of 50 lawyers and 30 law students.

The ICLU, driven by its volunteers, produces easy-to-read documents on legislation, gives legal aid, defends rights of protesters, and works for the release of prisoners granted bail by the court. It had also set up camps in Assam to help locals navigate the National Registration Citizens, and some of its members were part of a group that drafted guidelines for anti-lynching laws.

This citizen-led initiative, however, is only one of the many that have mushroomed in the last few years. These are run by people with full-time jobs and no funding, and a singular focus – to empower citizens and safeguard democratic and electoral processes.

On the eve of elections, Newslaundry spoke to founders and members of four such prominent organisations – ICLU, Maadhyam, Hate Speech Beda and Hindutva Watch – about their motivations, challenges and goals.

‘Can’t change system, can only do our part’

ICLU’s Tanwir told Newslaundry, he first thought of forming a network to provide legal aid and to make information accessible for the marginalised in 2017, when he read about an incident of mob lynching in Jharkhand.

“It was on the corner on page 13 of a newspaper. It shook me and made me realise how common these instances had become,” said Tanwir. “We’re clear on what we’re not doing – filing public interest litigations or forming fact-finding committees. We can’t change the system, we can only do our work. People need relief on a micro level.”

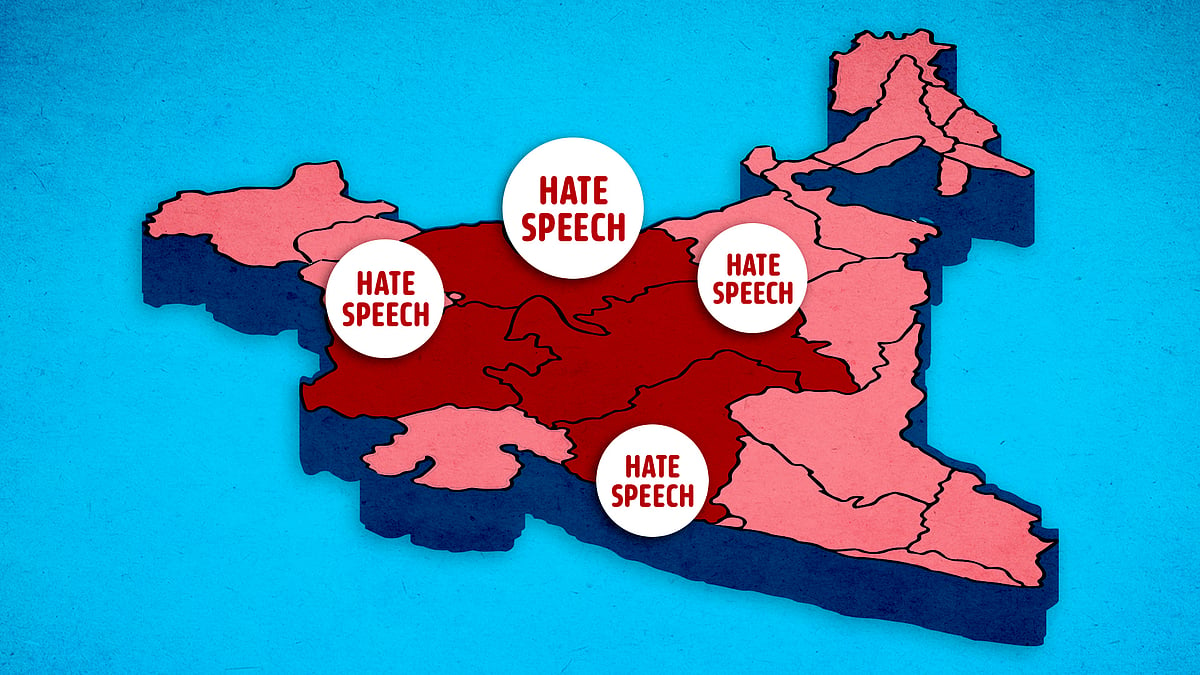

Similar to the ICLU, work piles up for Bengaluru-based Hate Speech Beda during elections. It began its poll season run by filing a complaint against BJP MP Tejasvi Surya for his “factually wrong and incendiary” statement allegedly calling for violence against Muslims.

Besides Surya, they filed police complaints seeking FIRs against several other political leaders for “spreading misinformation” and making “dangerous statements” against Muslims.

“It comes in waves, and elections are always a time we see an uptick of hate speech,” said Shilpa Prasad, a lawyer and one of the 30 core members of the group founded in 2020.

Speaking to Newslaundry, Prasad recalled how the collective of lawyers, media persons, environmentalists, doctors, researchers, and students was founded. “It was a response to the hate we were witnessing in Karnataka after CAA protests and Covid-19. We realised there was a need for a targeted campaign against hate speech, to systemically go about it.”

The group has been tracking hate speech, reporting it to the authorities, distributing pamphlets, and conducting workshops. It also has a media watch team that identifies hate speech in the media, and files complaints with self-regulatory bodies, such as NBDSA and NBF.

The NBDSA has acted on at least three complaints submitted by the group, pulling up Times Now, Network 18 Kannada, and Asianet Suvarna News. On its complaint, the Press Council of India censored a Mysore-based newspaper, Star of Mysore, over its editorial targeting Muslims.

The fines levied by these bodies are nominal, but that doesn't discourage them, said Prasad. “Of course, a fine of one lakh does not financially affect the media houses too much but it creates some impact. We can’t eradicate the hate but we can let them know that people are watching their actions.”

To bridge the void between citizens and the parliament, civic engagement initiative Maadhyam keeps a critical eye on the proceedings of the parliament. Founded in 2018 by lawyer Maansi Verma, 33, the initiative especially works to hold conversations on bills passed in the parliament.

This year, it also came up with a “chargesheet” against the central government, while its “Make Parliament Great Again” campaign listed expectations of citizens. Verma sent its copies to all political parties, including BJP, Congress, SP, Shiv Sena and AAP.

Verma told Newslaundry, the idea for the initiative struck her when she was a LAMP fellow, assisting a Member of Parliament. At the time, she witnessed how the controversial Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation) Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha amid resistance and re-promulgated four times by the President, and ultimately passed in the house on a day when there was low attendance.

The lawyer then wrote about “how due process was not followed” for passing the bill. After rejections from many media houses, the piece was eventually published by The Caravan. She said it made her realise that “there is no space for conversations about what happens in the parliament, how bills are passed without deliberation, opposition members are silenced” and rules are bypassed.

“I could see that things aren’t as they were supposed to be in an ideal democracy,” she said, “But it didn't seem to be making a difference to anyone that parliament democracy was being undermined.”

Blocking orders, backlash

The work may not be formalised, but it is not without its challenges – from trolling to a lack of adequate volunteers and action by law agencies.

In January this year, the government directed X to block the account of Hindutva Watch, a volunteer-driven research project that documents hate crimes. The website has also been blocked in India through directives reportedly issued under the IT Act.

But this is not the first instance of action against hate trackers. Two hate tracker initiatives, one by FactChecker and another by Hindustan Times, were allegedly forced to shut down soon after they were started.

Raqib Naik, a journalist and founder of Hindutva Watch, said despite knowing about the prospective backlash, he felt the need to come up with a hate tracker project, and approach it in a “methodical way that employs journalistic rigour.”

“I noticed that there were a lot of videos of hate crimes that would come up on X but when you search for them a few weeks later, they are untraceable. Critical evidence like this would disappear within weeks,” he told Newslaundry.

The blocking order, he said, will inversely impact law enforcement agencies that have “relied on the work by Hindutva Watch” to take cognizance of hate crimes on several occasions.

Naik said he had received at least 28 notices from X about such orders over the three years of running the Hindutva Watch account before the social media platform finally complied with the government.

“Not just them, but even the communities who are being targeted have been affected; they have a right to know what is happening in the country,” he said. “The blocking of our handle is denying them of this right.”

Naik, a 29-year-old Kashmiri journalist, moved to the US and founded Hindutva Watch in 2021. The organisation has around 15 volunteers across five continents. Meanwhile, India Hate Lab, another organisation run by Naik aimed at combating hate speech, has 11 volunteers.

The core team of Hindutva Watch documents hate crimes by watching hundreds of hours of hate speeches, and curating segments. Often, the people doing this work are from the same community that are being targeted.

“I pray sometimes that I don't come across a video of hate crime against a familiar face,” Naik said, adding that at times he zooms into videos to make sure it is not a relative or a friend.

668 hate speech events held in India in 2023, most of them in BJP states: Study

668 hate speech events held in India in 2023, most of them in BJP states: Study A hate-laden speech and murder: Why did Chetan Singh vanish from the news cycle?

A hate-laden speech and murder: Why did Chetan Singh vanish from the news cycle?NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.