Kutch: Struggle for water in ‘har ghar jal’ Gujarat, salt workers fight for livelihoods

Dalits and tribals, often at the receiving end of violence, say they don’t get enough government benefits.

Six years ago, Rakesh was inside his home in Siddhrana village, located in Siddhpur tehsil of Gujarat’s Patan district, when there was a knock at the door. A group of villagers stood outside, carefully on the other side of the threshold.

“There is a bhandara for the worship of Mahadev in the evening,” they said, referring to the distribution of free food. “Food has been arranged for the people of your community. There will be separate arrangements for sitting there.”

“Separate arrangements” is code for segregation because Rakesh is Dalit while the villagers inviting him are from dominant castes. Rakesh refused to attend. Another village then said he alone could sit with them while others from his community could not. Why? Because Rakesh has a government job which carries enough “prestige” to temporarily overrule his birth.

Rakesh refused again. “If I sit with you, my society will not sit with me. You have to make everyone sit together.”

The group immediately protested. Rakesh and 125 other Dalits eventually declined the invite altogether.

The invite is merely a symptom of horrific caste segregation and violence in Rakesh’s part of the world. “In Gujarat, people of our community are sometimes killed for drinking water from a public place. Sometimes they are stopped for riding horses at wedding processions,” he said. “Such incidents are everyday things.”

To protest against these horrors, Rakesh and 400 others were among thousands of Dalits in Gujarat who renounced Hinduism and converted to Buddhism on April 14, 2023, the 132nd birth anniversary of Dr BR Ambedkar. A year later, the state government issued a circular saying conversions from Hinduism to Buddhism and others must receive prior approval from a district magistrate.

While the circular was widely criticised in the media, Dalit social worker Chandramani told Newslaundry that conversions in Gujarat have been bound by the law since 2003. Those who had participated in the mass conversion last April had “applied in their districts”, he added.

But the circular is yet another reason for bitterness among Scheduled Castes in Gujarat, who say they face violence, discrimination and poverty with little intervention from the state. According to data from the union home ministry, 17,022 cases of atrocities against SCs were registered in Gujarat from 2009 to 2022. The highest – 1,477 – took place in 2017 and the lowest - 1,008 – in 2010.

In February this year, Hitendra Pithadia, the president of the state Congress SC department, told the assembly that the vigilance and monitoring committee, constituted by the Gujarat government to investigate atrocities against SC and ST communities, “has not held a single meeting in two years”. He accused the BJP-led government of not being “serious” about such crimes.

In the Lok Sabha constituency of Kutch, which votes on May 7, this reporter met families across the district to ask them about their struggles.

A battle for water

The Lok Sabha constituency of Kutch predominantly comprises Kutch district, which is also the largest district in India, and parts of Rajkot. Kutch is a reserved seat in the Lok Sabha for SC representatives. About 75 percent of its residents are Hindu and 21 percent Muslim. Amongst the Hindus, the Patidar community plays a decisive role.

According to the 2011 census for the district, SCs make up 12.3 percent and STs 1.05 percent. Only about 34.8 percent of the population lives in urban areas.

The BJP has won from Kutch in the last seven Lok Sabha polls from 1996 to 2019. The last non-BJP MP was Harilal Nanji Patel from the Congress in the early 1990s. In 2019, Vinod Chavda from the BJP won by over three lakh votes. Chavda will contest again from Kutch this year, taking on Congress’s Nitishbhai Lalan.

Bhuj is the headquarters of Kutch district, while Jakhau, Kandla and Mundra are the main ports. In Kandla port, we met Ghanshyam, who lives in a settlement in Gandhidham and works at the port.

Ghanshyam said his settlement receives running water only two days a week. He’s forced to queue from dawn and hopefully gets his turn to fill up pots and pans by evening. He also has to take leave from work on those two days, which drastically impacts his earnings. Along the coast, several others told this reporter they face similar issues.

This is crucial because in October 2022, state home minister Harsh Sanghvi had tweeted that Gujarat was officially a 100 percent ‘har ghar jal’ (water in every home) state. He said the state was now “self-reliant in the water sector” and that “from changing the lives of women to fulfilling the needs of tapwater in every home, the Modi government has done this”.

"पानी के क्षेत्र में गुजरात बना आत्मनिर्भर"

— Harsh Sanghavi (Modi ka Parivar) (@sanghaviharsh) October 26, 2022

पानी जीवन का आधार है, पानी की एक एक बूंद की कीमत गुजरातियों से ज्यादा शायद ही कोई जानता होगा।

महिलाओं के जीवन को परिवर्तित करने से लेकर, हर घर नल की जरूरतों को पूरा करके दिखाया है "मोदी सरकार" ने। pic.twitter.com/pNKBJSzx1G

In 2021, the state received Rs 852.65 crore in its first instalment under the Jal Jeevan Mission.

“The government doesn’t do what they say. There are many problems in this area,” said Ghanshyam. “Just look at the water. Modiji says water comes from the tap in every house but we have to work hard to get water. We haven’t received the benefits of Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana either. Due to all the problems, we’ve sent our children to the village but we have to stay here for work.”

Shankar, who lives near Mandvi port, told this reporter: “There are a lot of problems regarding water in this area. One has to buy RO [filtered] water for drinking. People say we live on the banks of the biggest source of water but this water is of no use. It’s a big problem. Many diseases arise from the water, even food cannot be cooked with it.”

Dhirendra from the fisherfolk community lives near Jakhau port. He said he has a BEd and an MA but there are no jobs to be had. When asked about water issues, he said, “Until two years ago, we used to get water with the help of the coast guard. The fishermen’s permanent settlement was demolished one and a half years ago. Many families live in bamboo huts. Other families left. We have to buy water for everything from eating to bathing.”

Nadeem, who depends on well water in Jakahu, said the water is “polluted” but people have no choice but to drink it. “There are water problems throughout the year,” he said. “Many governments have come and gone but the water problems in these border villages remain the same. There has been no improvement.”

His neighbour Ishrat Jahan added that in nearby villages, women travel 10 km to a well to fill water even though every household is supposed to get piped water. He said they’ve tried approaching the local administration but little happens.

“If the government cannot provide water, then what to expect from the government?” he asked. “The situation is serious. Cattle are dying in villages without water. If we are not able to get drinking water ourselves, how can we provide water to cattle?”

Struggles in the salt fields

Kutch is known for its salt marshes, manned by the Agariya people who have lived here for centuries. They work in the salt fields and their lives are defined by poverty and back-breaking work, with little changing in their circumstances over the years.

In Surajbari, located 10 km from the Arabian Sea, a community of Agariyas explained that the groundwater is 10 times saltier than seawater. They extract the water from tube wells and fill it into small fields measuring 25x25 metres. The water gradually evaporates, leaving white salt behind.

Every Agadiya family is responsible for between 30 and 60 such salt fields, explained Harnesh Pandya, president of the Agariya Heet Rakshak Manch. Workers produce 10 to 15 tonnes of salt every fortnight. The salt is loaded onto trucks and trains and sent to companies and factories across the country. Every Agariya family is responsible for 30 to 60 salt fields.

A labourer typically works for eight hours a day, wielding claw-like tools to ensure the salt doesn’t settle but forms grains instead. He is paid only Rs 70 per tonne of salt produced, across 40-degree weather in summer and five-degree cold in winter. During the monsoon, Surajbari is submerged so workers are unemployed.

“A family will live in the Rann for eight months,” said Pandya. “They make their own arrangements for cooking and living. This fight is only for two square meals. The salt is prepared not just by the hard work of these workers but by their tears too, which the whole country eats.”

Locals told this reporter that working in the salt all day changes their bone structure, to the extent that the bones do not burn on funeral pyres. Family members are forced to collect the bones after the fire is extinguished and bury them in salt graves.

Pandya added, “Recently, the forest department banned entry into the Little Rann of Kutch. Due to this, more than 1,200 Agariyas lost their livelihoods. All of them are part of communities like Chunwaliya Koli, Sandhi and Miyana. All the denotified tribes are mostly landless and completely dependent on salt for their bread.”

The blocking of Little Rann is pushing communities to possible starvation, Pandya said. While Gujarat produces over 76 percent of India’s salt, Little Rann contributes 20 percent of the total, with a 600-year-old history of production. Spanning an area of 5,000 square km between the districts of Patan, Morbi and Surendranagar, Agariya families often move there in September, staying until the farming season ends in April or May.

Notably, Little Rann was declared a sanctuary in 1973 for the Indian wild ass. Agariyas allege they are now called “illegal” encroachers under the Wildlife Protection Act.

The result is eviction notices and loss of income. Families told The Mooknayak that government officials said they had to be named in an official “survey and settlement report” to enter Little Rann, and that “90 percent of them” were not included. They were also asked to provide “documentary evidence” of their ownership of the land, which they did not possess.

Pandya’s group said that members of the community from four districts and seven talukas submitted joint appeals to the district and state administration last year asking for help.

“They met MLAs and concerned ministers. They also approached the National Green Tribunal and high court where cases related to Little Rann were being heard,” he said.

Land Conflict Watch reported that in September last year, the state government “decided to allow all traditional Agariyas to continue salt harvesting upon simple registration, the verification of which would be done during on-site survey”. It also said the list would be revised to permanently recognise seasonal rights. However, many of them still haven’t received permission to enter.

“The registration process was done in all the blocks and in September, many Agariyas moved to Chhote Raan. But without any reason, the Agariyas of Santalpur and Adesar were stopped from entering,” said Pandhya. “They were told a decision will be taken soon. The forest department said it will take some time to verify and finalise the list.”

Meanwhile, the labourers have lost income and livelihoods.

“We are repeatedly appealing to the MLA and the forest department,” said Narubhai, a member of the community whose family has been producing salt for six generations. “We aren’t even allowed to prepare the salt fields. Why is there such discrimination against us?”

And here too, the water woes continue.

“There is no water tank so people store water by tying plastic to a cot,” said Praveen, a member of the Manch. “Something must be done for them. I distributed plastic tanks to help needy families.”

This report was originally written in Hindi. It was translated to English by Shardool Katyayan.

This report has been published as part of the joint NL-TNM Election Fund and is supported by hundreds of readers. Click here to power our ground reports. It was executed in partnership with Mooknayak, and you can support their journalism here.

For reports that talk about real issues, we need a free press. On World Press Freedom Day 2024, power the independent media.

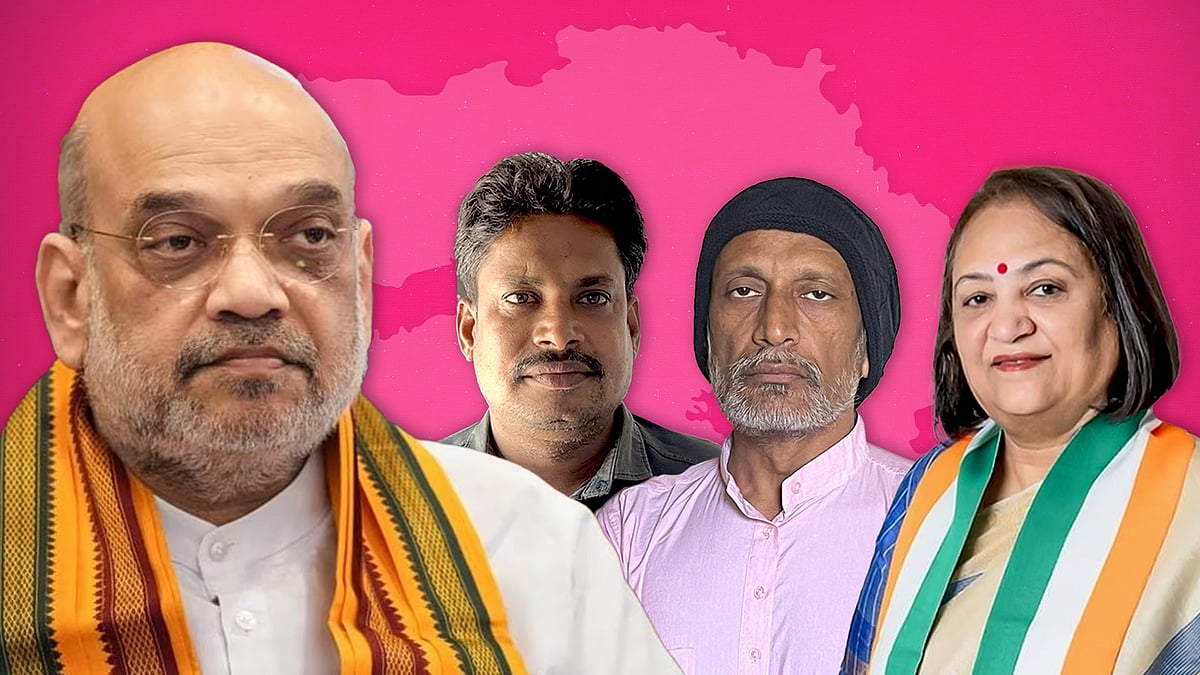

Can Amit Shah win with a margin of 10 lakh votes in Gandhinagar?

Can Amit Shah win with a margin of 10 lakh votes in Gandhinagar?NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.