Pro-Modi vs ‘anti-India’ diaspora: For a Labour govt, balancing act will be key in UK-India ties

First British Hindu ‘manifesto’ demands ban on JKLF and Sikhs for Justice.

In September 2019, weeks after the Modi government in India stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status through unilateral constitutional changes, the British Labour Party adopted a resolution at its annual conference condemning “the recent actions of the Government of India to revoke Article 370 and 35A of the Indian constitution and the special status” and supporting “international intervention in Kashmir and the call for a UN-led referendum”.

From India, the response was swift. “Clearly, this is an attempt at pandering to vote-bank interests. There is no question of engaging with the Labour Party or its representatives on this issue,” the MEA spokesperson said.

Labour faced a more severe backlash three months later, in the snap general elections that Prime Minister Boris Johnson called in December 2019. Hundreds of British Hindu Indians came together as a group called ‘British Hindu Indian Votes Matter’, channelling their outrage to canvass against Labour, calling its then leader Jeremy Corbyn “anti-India” and “anti-Hindu”. By then, Labour, sensing the mood, had already revised its resolution. As the party surveyed its worst-ever defeat in that election, an BHVIM claimed it had influenced results in 70 seats, including 22 where Labour was defeated, as well as those where Conservatives had won with larger margins and others where Labour won with smaller margins.

At 1.8 million, British Indians are the largest ethnic minority in the United Kingdom and an important political constituency. Hindus, numbering slightly under a million, are the largest religious group within this minority. And on the last weekend before the upcoming general elections in the UK on Thursday, July 4, they were wooed by both the Tories and Labour, which is widely expected to win these elections after 14 years in the opposition.

On the last weekend before the vote, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and his wife Akshaya Mruthy, visited the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Sanstha in London’s Neasden (also known as the Neasden Temple), where the Kenyan-born Sunak invoked his Hindu faith as his inspiration, saying he was “determined never to let [British Hindus] down”.

Yogivekdas Swami, the head of the temple, praised Sunak as an example for British Hindus, and said he had brought “pride” to the community.

“You have really raised the bar for the children in our community. It is now no longer enough to become just a doctor, a lawyer, an accountant because Indian parents across the country are now saying you can also become the Prime Minister,” the Swami was quoted as saying.

Keir Starmer – the Labour leader who could be the next Prime Minister, if the pollsters are right in predicting a historic rout of the Tories to below 100 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons – also visited a Hindu temple on the weekend, promising to stand by the Hindu community and trying to reverse the “anti-India, anti-Hindu” perception about his party.

Hindu ‘manifesto’

The emergence of Hindus as a pressure group in British politics corresponds roughly with the rise of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister of India. They are now a vocal and demanding section within the British Indian minority. In a trend that became starkly apparent in the 2015 British elections, Hindu voters are also driving a shift among British Indian voters from their decades-long allegiance to the Labour Party.

Indians have a long history of migration to the UK. Early migrants were working-class Indians, and Labour was the party that resonated with their work-life problems, such as racism and poor pay, and economic conditions. But with new waves of younger, professional Indians arriving on British shores over the last two and a half decades, coinciding with India’s economic liberalisation, and the rise of Hindutva and the BJP in India, the British Indian diaspora’s political preferences have undergone a change too. During this time, the Overseas Friends of Bharatiya Janata Party, set up in the UK in the early 1990s, emerged as a prominent face of Hindu British Indians.

According to a report published earlier this year by the King’s College-hosted think tank UK In a Changing Europe, so long as British Indians based their political preference on domestic issues that affected them directly, they affiliated with Labour, but “inter-communal tensions [such as the 2022 Leicester riots], plus interference from outside, have helped weaken links between British Indians and Labour”.

Ahead of this election, for the first time, several organisations of British Hindus joined hands to bring out a “Hindu manifesto”, following the example of the British Muslim and Sikh communities, who have long brought out their own “manifestos” at elections.

The manifesto states that Hindu votes are “conditional upon candidates’ commitment to [the] expectations” listed in it. At the top of the list is “recognising Hinduphobia as a hate crime and proscribing organisations and prosecuting individuals engaging in it and attacking the sovereignty and integrity of India, including but not limited to JKLF, LeT and Sikhs for Justice”.

Among the definitions of “anti-Hindu hate”, the manifesto accuses Hindus and others who speak about “Hinduphobia” or organise around it “of being pawns of violent, political agendas”. Asserting that all inequity in Indian society – caste, sati, misogyny, communal violence, or destroying places of worship – stems from Hinduism, is also anti-Hindu hate, the manifesto states. The British Equality Act of 2010, brought in by the Gordon Brown-headed Labour government, covers caste discrimination through a provision that, by order of a minister, caste may be treated as an aspect of race. The manifesto does not mention the Act, but its indirect inclusion of caste is one more grievance that British Indians hold against Labour.

The manifesto also seeks the establishment of Hindu faith schools, government funds for protection of Hindu places of worship, visas for Hindu priests to run temple, and for elderly parents because “three generations often live together”, caring for the old and young, and ensuring cultural continuity through the “transmission” of customs, wisdom and heritage to the young.

The manifesto asks candidates to sign off on these and other pledges in return for the Hindu vote. It’s not clear how many candidates have done so. Hindus in the UK, like all other religious groups, are certainly no political monolith. They mirror the pro- and anti-Hindutva polarisation in India (their national origins are diverse too), and their political preferences are also influenced by their education, and age.

According to the 2021 British census, Muslims (of diverse nationalities) are the third largest population group by faith in the UK (after Christianity, and “No Religion”), and Hindus are in fourth place. Even though Conservatives are now getting more British Indian votes, there is no perceptible shift among Muslims and Sikhs from their traditional support to Labour to the Tories.

The Muslim Council of Britain launched its own set of 10 pledges, asking the next government to build a more inclusive and diverse society, and adopt a consensus definition of Islamophobia. The demand comes against a political background that has seen the rise of Nigel Farage of the far-right Reform UK party, and the toxicity of Suella Braverman, a minister in Rishi Sunak’s government.

The “Muslim manifesto” demands that the UK must uphold “international law”, and “international peace and justice”, “end Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands, and recognise the state of Palestine”. Unlike the Hindu manifesto, it also flags cost of living issues, better housing, and the need for a fair and diverse media.

The demands in the Sikh manifesto are for “MPs need to urge the UK government to work with other countries to urgently address the global rise of Hindu extremism (Hindutva)”, and for the British government to “work with their partners in the Five Eyes nations and other western countries to confront the threat of transnational repression and political interference by the Indian government that is targeting its opponents in the diaspora”. It also wants the “unconditional and permanent release” of all Sikh “political prisoners” in Indian jails, including Jagtar Singh Johal.

The manifesto reminds Labour about its previous election promise in 2017 and 2019 “to hold an independent public inquiry into the actions of the UK Government in advising and assisting in the 1984 Sikh Genocide, and the restrictions the UK Government imposed on British Sikhs in the 1980s”. The manifesto says it would be a fitting to announce the investigation in 2024, the 40th anniversary of Operation Bluestar.

India-UK ties, diaspora and Hindutva

Less than two years ago, the September 2022 Hindu-Muslim riots in Leicester, one of the two non-white majority cities in England (the other is Birmingham), brought attention to the spillover effect of India’s Hindu nationalist politics abroad, the underbelly of the “living bridge” between the India and the UK, the term that Prime Minister Modi used to describe the British Indian diaspora.

Fact checkers, such as Logically and investigators, highlighted the role of external social media actors in stoking trouble in Leicester with fake information. Logically said out of the 20,000 tweets containing geotagged information on the riots during the incidents, 18,000 were geotagged to India. Two investigations are currently underway into the riots.

Although the Hindu manifesto asserts that the connect of British Hindus to “Bharat” is spiritual and not political, the British polity detects a clear political link. This is why, as Labour attempted to reset ties with anti-Labour sections of British Hindu voters, two delegations of Labour’s Shadow cabinet hotfooted it to Delhi in February.

Shadow foreign secretary David Lammy and Shadow Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds came first, while shadow deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner followed, with British Indian MP Navendu Mishra and Vimal Choksi, a British Indian local government councillor in a Manchester Borough. Their visits were as much a “fam trip” to get to know members of the Modi government, as they were an outreach to pro-Modi British Indian voters back home.

Last week, speaking at the India Global Forum, Lammy said he hopes to travel again to India before the end of July as the new Foreign Secretary, and that Labour was “ready to go” on the Free Trade Agreement, on which India and the Conservative government held 13 rounds of talks.

The challenge for a Labour government will be to insulate its ties with India from the demands of various competing and rival diaspora groups – Hindus, Kashmiris, Sikhs, and Pakistanis – some with close ties to the BJP and the Modi government and no longer loyal to the party, and some ranged against Delhi but whose loyalty to Labour has stayed solid through the years.

Small teams can do great things. All it takes is a subscription. Subscribe now and power Newslaundry’s work.

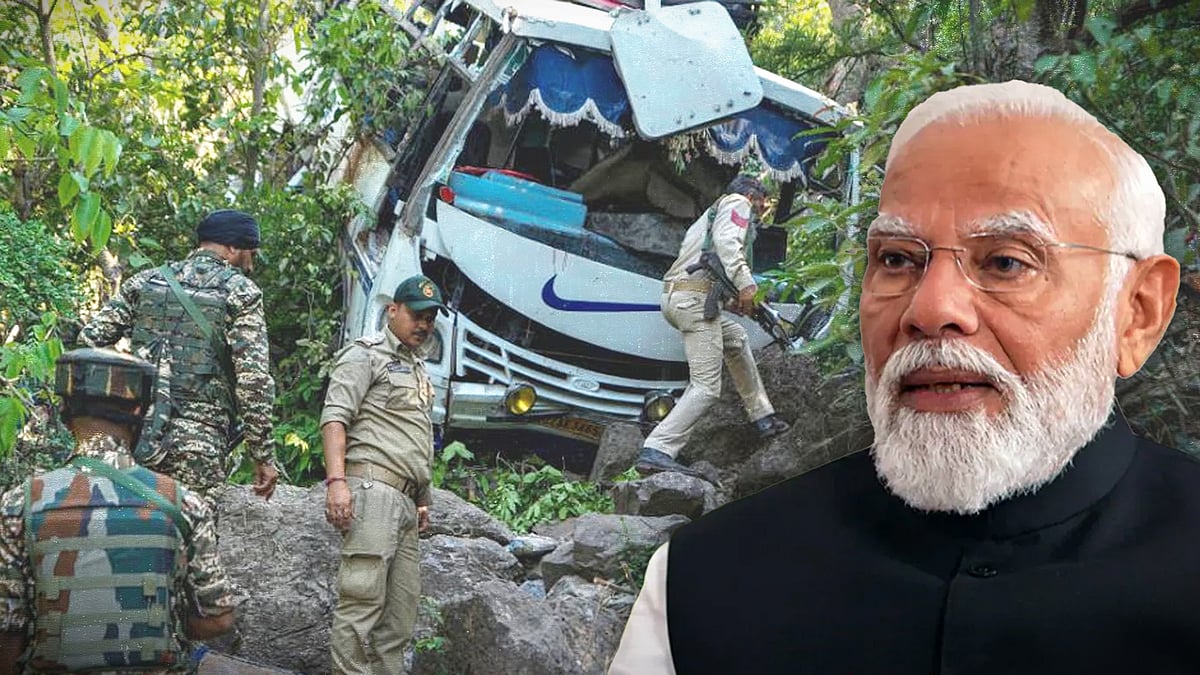

Impact on Amarnath yatra, assembly poll plan: J&K attacks pose early test for Modi 3.0, opposition

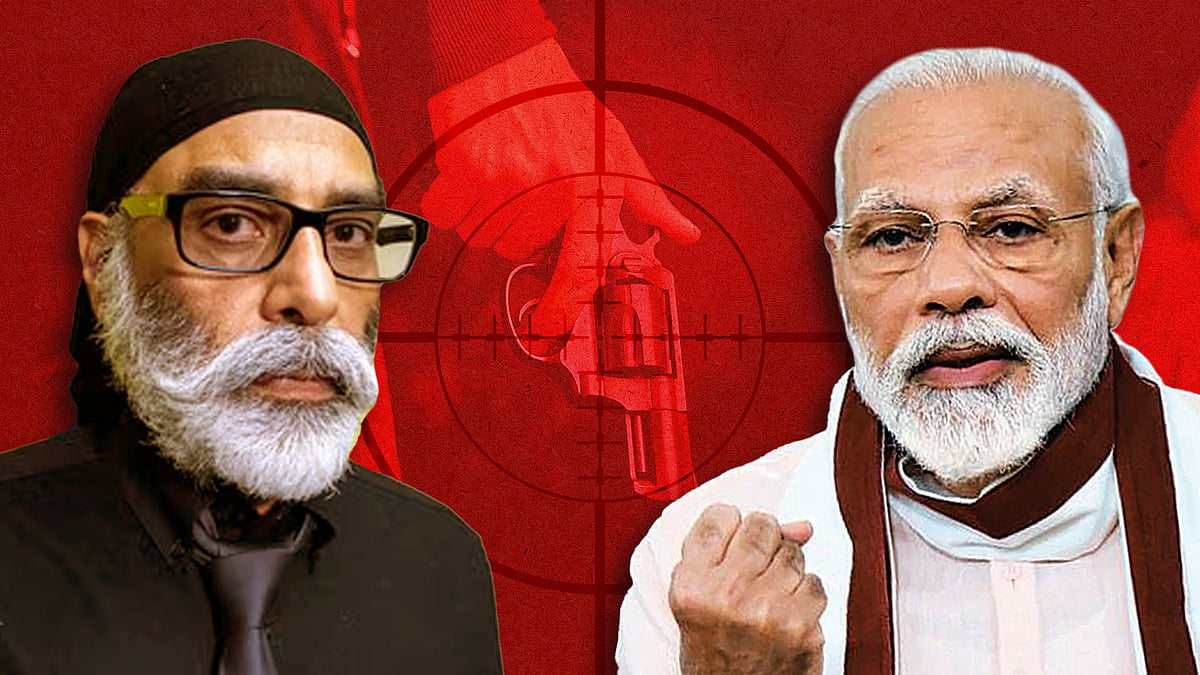

Impact on Amarnath yatra, assembly poll plan: J&K attacks pose early test for Modi 3.0, opposition In plot to kill Pannun, India’s claim of ‘rogue’ operatives risks comparison with Pakistan

In plot to kill Pannun, India’s claim of ‘rogue’ operatives risks comparison with Pakistan