Five years post-Article 370: What Pakistan is signalling Delhi from Jammu

Preoccupation with TTP violence on its western border has not ended Pakistan Army’s interest in J&K.

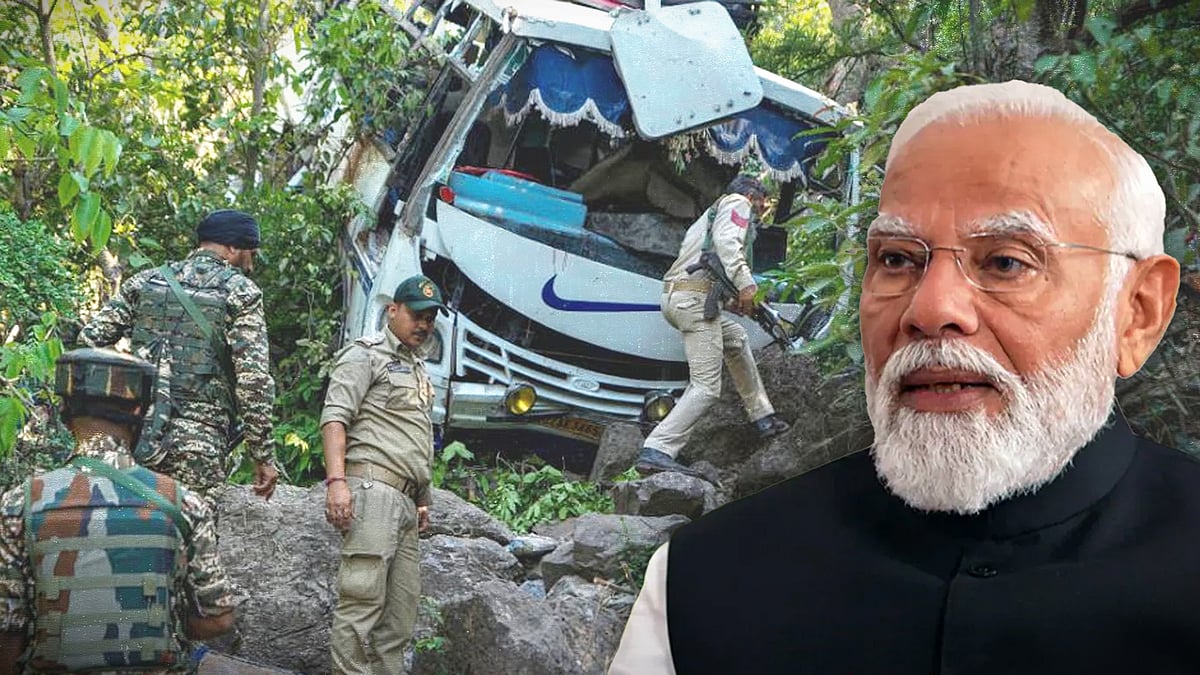

On July 30, Union minister of state for home affairs Nityanand Rai told the Lok Sabha that 14 civilians and 14 soldiers have been killed in Jammu and Kashmir this year. As they have every year since 2019, the numbers belie the government's claim that the abolition of Article 370 and Jammu and Kashmir’s special status has spelled an end to terrorism. In the five years that will mark that decision on August 5, the Union Territory's security challenges have undergone changes, but they remain grave.

As has been obvious since at least 2021, the infiltration and attacks have shifted to Jammu from Kashmir. The attacks are being carried out by highly-trained persons adept at remaining hidden over long periods and skilled in the use of weapons, which more or less rules out local recruits. They carry sophisticated NATO-issue weapons, freely available in the Afpak region after the hurried pullout in August 2021. They are no longer fidayeen attackers religiously committed to fighting until death. Instead, typically they hit and run, picking out more targets during the search operations after each big attack.

The incidents in Jammu over the last three years show that the highly vaunted 2016 “surgical strike” and the 2019 Balakot strike did not end Pakistan’s appetite for raking up trouble in J&K.

Nor has the Pakistani army’s preoccupation with its own security woes ended its interest in J&K. If anything, the opposite is true. The uptick in the incidents in Jammu has come at the same time as an increase in the violence unleashed by the Tehreek-e-Taliban in Pakistan and in the activities of the Baloch insurgency. The attacks in Jammu have proved wrong the Indian assumption that a Pakistan tied up on its western border will be silent on its east.

The Jammu region’s security graph started to go south just months after the removal of Article 370. Kashmir was saturated with troops, and the LoC there was tougher to infiltrate. Jammu, almost free of terrorist violence since the early 2000s, offered an alternative to terrorist groups with an easier-to-infiltrate LoC and thinner security further inland. Troops from Jammu were moved to the Line of Actual Control at the time of the Chinese incursion in 2020 and the Galwan clash in June. Since October 2021, the attacks in Jammu on soldiers and civilians have put India’s security forces in the region on the backfoot.

India blamed for TTP

The TTP is now said to be the biggest terrorist group operating in Afghanistan. Pakistan has failed in attempts to persuade the Taliban regime in Afghanistan to rein them in. Since about 2008, months after the TTP came together as a collective of terror groups to avenge the Pakistan Army’s 2007 storming of the Lal Masjid in Islamabad, the Pakistani establishment has pointed to an Indian hand behind the group. Since the TTP's resurgence after the Afghan Taliban’s return to power in 2021, these allegations have grown louder and are linked to the alleged Indian hand behind the Baloch insurgency.

A statement made by defence minister Rajnath Singh during the 2024 elections – echoing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “ghus ke marenge (will enter and kill)” remark after the 2019 Balakot strike – appeared to confirm an alleged Indian hand in a series of targeted assassinations on Pakistani soil and in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, and served to popularise the notion in Pakistan that India is behind the violence in that country. Another statement by Prime Minister Narendra Modi attacking the Congress for being “scared” of Pakistan mocked the neighbour as a defeated and broken country that did not have the money to buy even wheat flour.

In recent weeks, from the day Modi was sworn in as Prime Minister for the third time on June 9, the security situation in Jammu has deteriorated further, and security forces are struggling to gain an upper hand in the deadly game of hide and seek mostly initiated by the terrorists.

Modi's remarks in Kargil on July 25, the anniversary of India’s victory in the Kargil war, that Pakistan had “learnt no lessons from history” appeared to acknowledge that Pakistan was not as broken as he had suggested earlier in the year.

What Pakistan army wants

In the perverse way that India-Pakistan relations play out, this was perhaps exactly the validation that the Pakistan Army may have wanted from the Indian Prime Minister – that it is down and out, but not dead, as he had suggested during the election campaign. The attacks in Jammu have reminded India that five years after Article 370, Pakistan has not been rendered irrelevant to the state, as claimed by the Indian leadership, and still holds some cards.

With Pakistan embroiled in political battles of its own making over the last three years on its domestic turf, the Indian allegation against the Pakistan Army of involvement in the Jammu attacks helps to diffuse pressure building up on it at home. The Pakistan Army has been mocked for threatening and jailing Pakistani politicians and citizens who oppose it while failing to respond to India and the rhetoric of the Indian leadership. Kashmir remains an emotional issue among large sections of Pakistanis, who feel they must never abandon the issue or make any deal with India that compromises the dream that Kashmir will become a part of Pakistan.

For Pakistan, the allegation of the Jammu attacks works exactly in the same way as the accusation against India of carrying out assassinations of its “enemies” across the border and other countries boosted Modi’s strong man image. It has helped the Pakistan Army capture some lost ground at home, even while Pakistan officially appears to deny involvement.

Pakistan maintains that it wants “peace and stability in the region”, and “always desired cooperative relations with all its neighbours, including India”, and “wants constructive dialogue and engagement to resolve Kashmir and all outstanding issues”.

At this point, as India deals with the challenge in Jammu, and possible assembly elections in the Union Territory before the end of September, the likelihood of a Modi-Sharif-led India-Pakistan talks, much anticipated earlier this year, has all but vanished. The political mood in India is definitely not for talking to Pakistan.

How India is responding

Indian security forces are now focusing on plugging the infiltration and strengthening the counter-insurgency capabilities of the troops in the area. A large contingent of the BSF troops has been sent to Jammu to guard the International Boundary in the region, which comprises a stretch of over 100 km and presents more opportunities for infiltration than the Line of Control. More Special Forces of the army have been dispatched to Jammu for enhancing counter-insurgency operations, which have been another weak point in the Jammu area. Intelligence is perhaps the weakest link and would need a rebuilding of relationships and trust in an area where the cooperation of the Gujar community in the border districts was key to freeing the area from entrenched Pakistani jihadist groups.

But in the long run, both sides know that the problem in Kashmir needs diplomatic minds. That, in turn, needs leaders of exceptional courage on both sides, capable of making compromises, and with the ability to sell those to their own domestic constituencies. For India and Pakistan, that moment seems still far away.

If you’re reading this piece, you’re not seeing a single advertisement. That’s because Newslaundry powers ad-free journalism that’s truly in public interest. Support our work and subscribe today.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress) Lone wolf, hiding spot, security: How Rajiv assassination bid was similar to Trump’s, with a crucial difference

Lone wolf, hiding spot, security: How Rajiv assassination bid was similar to Trump’s, with a crucial difference Impact on Amarnath yatra, assembly poll plan: J&K attacks pose early test for Modi 3.0, opposition

Impact on Amarnath yatra, assembly poll plan: J&K attacks pose early test for Modi 3.0, opposition In plot to kill Pannun, India’s claim of ‘rogue’ operatives risks comparison with Pakistan

In plot to kill Pannun, India’s claim of ‘rogue’ operatives risks comparison with Pakistan Does CAA spell end of the road for visas to Afghans? Three takeaways from India’s visit to Kabul

Does CAA spell end of the road for visas to Afghans? Three takeaways from India’s visit to Kabul