With the largest legal wing in Tamil Nadu, why DMK banks on it to get things done

From high-profile national cases to local wins, the party is sharpening its legal skills ahead of local polls.

“If the court verdict had not come, I wouldn’t have known what to do.”

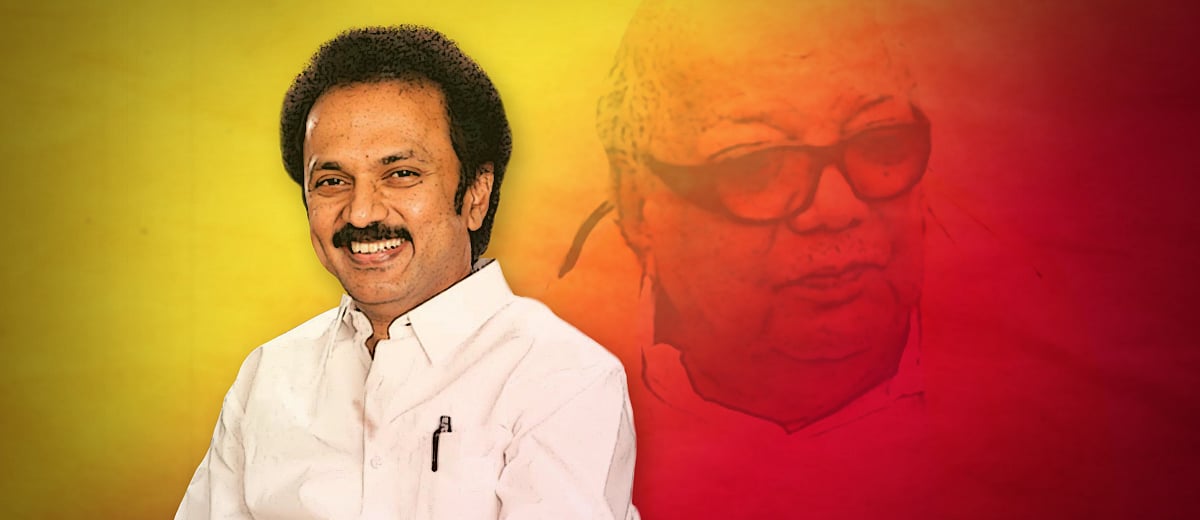

These are the words of Tamil Nadu chief minister MK Stalin, his voice choked with emotion, as he described the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s legal battle to ensure that his father and DMK patriarch, M Karunanidhi, got his final resting place at Chennai’s Marina Beach.

Karunanidhi, who died in August 2018, had wanted to be buried at Marina Beach alongside the memorial of his political mentor and Dravidian legend CN Annadurai. Hours before his death, Stalin wrote to the then AIADMK government about the burial, and also visited the residence of chief minister Edapaddi K Palaniswami, his family members in tow.

The state government refused permission.

So, the DMK’s legal wing – led by its senior member P Wilson – sprang into action, moving an urgent petition at the Madras High Court.

“It was a fight to acquire a six-foot space at Marina beach,” Wilson said.

After a midnight hearing that lasted two hours, the court judgement arrived the following day, directing the government to allot space for Karunanidhi’s burial on Marina Beach. After all, his fiercest opponent J Jayalalithaa and longtime friend turned rival MG Ramachandran were buried there too.

To no one’s surprise, Wilson was rewarded with a Rajya Sabha berth in 2019.

But this was just another chapter in the DMK’s legal prowess. The party’s legal wing has made headlines several times.

In 2014, a special court in Karnataka headed by Justice John Michael D'Cunha had convicted Jayalalithaa and three others in a disproportionate assets case. Interestingly, it had been DMK general secretary K Anbazhagan, who is also a member of its legal wing, who had approached the Supreme Court to transfer the trial to Karnataka, stating that a fair trial was not possible in Tamil Nadu where Jayalalithaa was chief minister at the time.

Appearing in the case were R Shanmugasundaram, then president of the legal wing, and advocates Kumaresan and A Saravanan. Shanmugasundaram and Kumaresan were later appointed advocate general and additional advocate general, respectively, of the Madras High Court, while Saravanan is presently the deputy secretary of the DMK’s press relations wing.

Also, soon after the judgement, the AIADMK’s P Karthiyayini, who was the mayor of Vellore, passed a resolution condemning it. Effigies of D’Cunha were even burned on the streets of Vellore. The DMK’s legal wing filed a writ petition at the Madras High Court directing her to quash the resolution and also to send a written apology to D’Cunha.

Then, when the Karnataka High Court struck down the conviction in 2015, the DMK went all the way to the Supreme Court to get the judgement quashed and to confirm the trial court’s order.

“The AIADMK fought tooth and nail to derail the case,” said R Viduthalai, the president of the legal wing and the former advocate general of Tamil Nadu. “But our legal strategy was to systematically fight it.”

The DMK’s lawyers are known to keep AIADMK leaders and ministers, even the chief minister, on their toes, filing a slew of cases to make their point. The AIADMK does not possess the same vigour; in fact, according to a senior member of the AIADMK, Jayalalithaa once scoffed at her own party’s legal team for not being “as strong” as their rival.

The structure

On the evening of November 1, Anna Arivalayam, the DMK’s headquarters on Chennai’s Mount Road, was buzzing with party cadres and volunteers. The legal team was assembled in a spacious room, alongside dozens of legal tomes and photos of Karunanidhi and Stalin.

Hours before, the Madras High Court had struck down the 10.5 percent internal reservation that had been given to the Vanniyar community. The bill had been put forward by the AIADMK government and the DMK government had issued an order for its implementation in July.

The Supreme Court has now agreed to consider a batch of appeals – filed by the state of Tamil Nadu and others – against the high court order.

Back in November, plans were underway on the DMK’s next move.

Flipping through a 186-page document prepared to brief Stalin on the matter, Viduthalai said, “Even though the AIADMK government enacted the law, we don’t want to let go of it. Committed to social justice, we decided to file an appeal at the Supreme Court.”

The Madras High Court had cited the lack of data to back up the reservation order, so discussions were also underway on conducting a population census.

But this was just part of the legal wing’s daily work.

The DMK’s legal wing comprises a president, a secretary, five joint secretaries, four deputy secretaries, 10 headquarter advocates, 72 district organisers, and 8,000 advocates working in Tamil Nadu and Puducherry. No other party legal wing in the state comes close.

According to R Girirajan, its secretary, “15 percent of the practising advocates in Tamil Nadu are part of the DMK’s legal membership”.

As a result, the DMK believes in in-house talent when fighting high-profile cases – in stark contrast to the AIADMK.

“It never flies lawyers down from Delhi to fight its cases,” said a political journalist. “But the AIADMK is completely opposite. Right from Jayalalithaa to her protégés Edappadi K Palaniswami and O Panneerselvam, the AIADMK leadership have air-dashed top lawyers who mostly argue in the Supreme Court to defend them in the Madras High Court.”

For instance, the journalist said, BJP leader Ravi Shankar Prasad was Jayalalithaa’s “favourite lawyer” at one point.

An ongoing fight

In October this year, the directorate of vigilance and anti-corruption registered an FIR against former AIADMK minister C Vijayabaskar, citing a disproportionate income of Rs 27.22 crore. He is the fourth former minister – after MR Vijayabhaskar, SP Velumani, and KC Veeramani – to come under the scanner in the past six months. A fifth former minister, P Thangamani, also had his house raided as well as 69 locations searched in connection with him.

While the DMK’s legal wing is tight-lipped about this spate of action, one of its members said, on the condition of anonymity, “We submitted petitions against these ministers two years ago. But due to pressure from the then AIADMK government, the directorate could not progress on it.”

The party believes its strength lies in “working from the grassroots” to build legal cases. “The legal wing members in districts are in constant touch with party cadres and social activists who provide information about rivals,” explained the source.

Among its other high-profile cases are the DMK’s challenging of the Citizenship Amendment Act and the three farm laws in the Supreme Court. “We are the first party to get a stay from the Supreme Court this year against the implementation of the farm laws,” Wilson said.

When it comes to local issues, the DMK’s local wing had also filed a public interest litigation in the Madras High Court through P Wilson, challenging Jayalalithaa’s plan to convert Chennai’s Anna Centenary Library, inaugurated by Karunanidhi in 2011, into a hospital. The DMK was successful; the high court directed the AIADMK government to also maintain and upgrade the library.

With urban local body polls in Tamil Nadu likely to happen in the next three months, the DMK’s legal team is currently busy planning its poll strategy.

“The legal team members are in constant touch with party cadres on WhatsApp groups and by conducting regular meetings at the party office,” said a member of the legal team.

Update: The spelling of MR Vijayabhaskar has been corrected. Stalin wrote to the government hours before Karunanidhi's death, not after. This has been corrected. The errors are regretted.

In pictures: DMK and allies lead massive rally against Citizenship Amendment Act in Chennai

In pictures: DMK and allies lead massive rally against Citizenship Amendment Act in Chennai DMK’s role as kingmaker could prevail even after Kalaignar’s death

DMK’s role as kingmaker could prevail even after Kalaignar’s death