Inside the online cult of #JusticeforSSR

The story of three men united by their fever-pitch resentment towards Rhea Chakraborty, and their anger and grief at the death of a Bollywood star.

A picture posted on a popular Facebook group shows actor Rhea Chakraborty next to a coronavirus illustration. “Which virus is more dangerous?” shouts the text on the image. The caption says: “2020 worst year in the history of mankind. The two most dangerous virus against humanity.”

The Facebook group in question is called “Justice for Sushant Singh Rajput”. With over one lakh followers, it’s peppered with posts hashtagged #ArrestRheaChakraborty and #IAmSushant.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“She should be hanged,” said Singh Dheeraj, one of the group’s five administrators. “But then again, in our country, it took very long for even Afzal Guru or Yakub Memon to be hanged..."

Dheeraj is a final-year engineering student in Faridabad. He agreed to talk to me over a Facebook Messenger call only after he confirmed that I’m a “nationalist”. “I’m against anti-nationalism,” he told me. About being one of the admins of the Facebook group, he said, chuckling: “I have not told my parents or friends. They will think that I am not focusing on my studies.”

For a nation obsessed with Bigg Boss, viewers no longer need to wait for an episode to be shot and aired. A version of this reality show, well-known for its voyeuristic appeal, plays out all day, every day, on social media and TV news screens. Ever since actor Sushant Singh Rajput died in June, the saga that followed has unfolded on our screens, and the past month has been particularly binge-worthy.

In a profile by the New York Times in June, talk show host Jon Stewart said, “Twenty-four-hour news networks are built for one thing, and that’s 9/11. There are very few events that would justify being covered 24 hours a day, seven days a week. So in the absence of urgency, they have to create it.”

And this is exactly what’s happened following Rajput’s death. Except this isn’t a movie — Chakraborty cannot take off her make-up and go home at the end of the day. Instead, she’s been thrust into a real-life trial by the media, where everyone watching, from national television anchors to quiet college-going students, has turned jurist.

In the process, Chakraborty has been torn apart by leading TV news channels, which demand her arrest, accuse her of “black magic” , camp out outside her building, pass off conspiracy theories as “news”, and conduct “postmortems” of Rajput himself. Republic’s Arnab Goswami screaming about drugs is only surpassed by Times Now’s Navika Kumar breathlessly running into the studio claiming to have a bag full of incriminating documents.

“It isn’t that Arnab or Navika don’t know what they’re doing,” said Pratik Sinha, founder of fact-checking site Alt News. “They know exactly what and why they go on camera for. They have people to please.”

Instead, it’s worth asking why young men and women like Dheeraj, who have never met either Rajput or Chakraborty, suddenly find themselves dedicating hours to administering Facebook groups that seek “justice for Sushant”.

For this, I spoke to three men – Saahil Chaudhary, an aspiring actor/model; Surjeet Singh Rathore, a member of the Karni Sena, a caste Hindu group; and Dheeraj. What links them is their fever-pitch resentment towards Chakraborty, and their anger and grief at the death of a Bollywood star.

Humans of #ArrestRheaChakraborty

Over the course of lengthy conversations, I asked all the three men where they found their conviction to convict Rhea Chakraborty.

Singh Dheeraj

Dheeraj hadn’t been a big fan of Rajput; what drew him was the fact that Rajput, like himself, was also from Bihar and managed to make it big in Bollywood.

For Dheeraj, the logic is fairly simple as to why he believes that Rajput was murdered, and did not die by suicide.

“How can they suddenly call him crazy now?” he said, possibly referring to reports on Rajput’s mental health. “It must have something to do with the fact that Rhea was living with him, right?”

This is a popular theory. Rajput’s therapist broke confidentiality last month and said the actor had depression and bipolar disorder. While the therapist also said Chakraborty was his “strongest support”, Rajput’s family has claimed that he “started having mental problems” after Chakraborty “came into his life”.

When I asked Dheeraj what kind of changes he thinks Chakraborty brought into Rajput’s life, he paused and came up with this anecdote, which he said is tied to the idea of an “ideal home”.

“Agar Salman [Khan] ki girlfriend ya wife aur Salman ke beech scene hua, toh kiska chalega? Salman ka hi chalega. Aur jabki yahan par Sushant aur Rhea ke sath jo scene hua, usme kiska chala tha? Rhea ka chala tha,” he said. (If something happens between Salman Khan and his girlfriend or wife, who will win? Salman will. And here, if something happened between Sushant and Rhea, who used to win? Rhea used to.)

But why did he think Chakraborty was controlling Rajput? Dheeraj brought up how Chakraborty tried to “change” Rajput’s staff members and friends.

“She had things to hide...look how she was acting with Mahesh Bhatt,” he said. “Was it correct of her to behave that way when she was with Sushant? Anyway, I am a nationalist, I am anti-Bollywood, anti-Rhea and anti-all these drugs and alcohol she used to do.” He refused to elaborate further.

This feeds into the image of Chakraborty constructed by the mainstream media. Photos of her posing on a beach in swimwear, or videos of her working out in sportswear are repeatedly shown during panel discussions, suggesting to viewers, like Dheeraj, that she’s some sort of promiscuous, gold-digging seductress with no “morality” or “culture”.

After some hesitation, he admitted that he believes Chakraborty deserves capital punishment, though he was quick to add: “Justice should be achieved but not hanging. Anyway in our country it was already difficult to hang people like Yakub Memon or Afzal Guru so obviously she cannot be hanged...but she should be punished...Women are like goddesses for me.”

Dheeraj didn’t watch Dil Bechara, the movie starring Rajput that released after the latter’s death, because he was juggling between his studies and the Facebook group. He also spends a large part of his day “counselling” women, he said. “Him [Rajput] going away has caused a lot of sadness to many girls,” he explained. “I send them videos...I try to make them understand.”

Saahil Chaudhary

Not far from Dheeraj, in the same state of Haryana, Saahil Chaudhary took to his YouTube channel on August 27, minutes after Chakraborty gave her first television interview to Rajdeep Sardesai on Aaj Tak.

Wearing a fitted white t-shirt and a neatly shaped beard, Chaudhary folded his hands and addressed his two lakh followers: “Somebody please hammer Rajdeep Sardesai’s head.” He spewed expletives against Chakraborty — zaleel aurath, haram ki bachhi and madarchodd ki bachhi being some of them — while his followers echoed his views gleefully in the comments section below, calling Chakraborty a “prostitute” and a “lady Dawood”.

This video received over 2.85 lakh views on YouTube.

Chaudhary has been busy for the last few months, providing daily updates on the investigation into Rajput’s death. He posted his first video on June 17, two days after Rajput died, telling his viewers that it was his “duty” to “expose the dirty secrets of Bollywood”.

In the video, Chaudhary claimed to have met Rajput “four or five times”. “He was such a gentleman, so kind-hearted. Today, I’m not going to spare anyone.” Since then, Chaudhary has uploaded 48 similar videos. According to him, Chakraborty must be arrested at once and the powerful in Bollywood should be shamed.

Importantly, when I spoke to Chaudhary, he denied having ever met the actor. During our conversation, his own frustrations at not being able to “make it big” in Bollywood were evident. “Out of lakhs of people, one got a chance and he became a star, but then you killed him?” he said. “What the fuck? You murdered him?”

Chaudhary runs a gym in Haryana, and has been trying to make it as an actor and model for over 10 years. Unable to be cast even as the friend of the hero, he started to explore YouTube to make himself more visible, he said. From cooking videos to workout videos to health tips and now the Rajput case, he feels like he’s finally found a platform to gain some stardom.

Although, he added, none of his videos on YouTube are monetised. Chaudhary has over two lakh subscribers on his channel. His most-watched video, with over two million views, is regarding who Chakraborty is dating.

When I asked him for the source of his information to declare Chakraborty guilty, Chaudhary said that people sent him articles and photos that he “verifies using logic”. After this “verification”, he concluded: “Rhea is hiding facts and is involved in the murder.” During the course of our chat, he also claimed that Chakraborty is a “gold-digger” who was having an affair with director Mahesh Bhatt.

So, what would he tell Chakraborty if he ever met her? “I don’t want to talk to her,” he replied. “I will simply do what the entire public wants to do: uske kaan ke neeche bajaunga main. I will give her a tight slap. I am sure that when this happens, the public will be satisfied. With this one slap, Sushant Singh’s parents and sisters will be at peace.”

Surjeet Singh Rathore

YouTube is Chaudhary’s platform of choice, but Surjeet Singh Rathore came into the limelight when he appeared on Arnab Goswami’s primetime show on Republic Bharat on August 21.

The show was hashtagged #WhySorryRhea, and Rathore was introduced as an “eyewitness” who was reportedly present when Chakraborty saw Rajput’s body at the Cooper Hospital mortuary. According to Rathore, Chakraborty “confessed” to her crime then; she placed her hand on her chest and said, “Sorry, babu.”

“Why is she saying sorry? Was she involved?” Rathore asked Goswami, who took long, dramatic pauses and repeatedly asked Rathore to describe Chakraborty’s demeanour.

Rathore is a member of the Karni Sena, a Rajput group. When I spoke to him on the telephone, he said he was in Rajasthan, the Karni Sena’s home state, from where he would “speak the truth”. After appearing on Republic, he claimed, Mumbai became “unsafe” for him. “I am not scared,” he added. “If something happens to me or Kangana Ranaut, Karni Sena poori Hindustan mein aag lagaenge. The Karni Sena will set fire to the whole of India.”

What does that mean? He replied, “Don’t you remember our Padmavat movement?”

Here’s a quick refresher: In 2017, the Karni Sena led a violent campaign against Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s movie Padmavat, claiming it tarnished the reputation of Rajputs and misappropriated history. Before the movie was released, Karni Sena workers vandalised the film set, slapped the director, trashed a theatre playing the movie’s trailer, threatened to cut off actor Deepika Padukone’s nose and behead Padukone and Bhansali, moved petitions to ban the film, and received support from the Bharatiya Janata Party.

The group eventually retreated when Padmavat was released, saying there was, after all, “nothing objectionable” in the film.

Rathore told me he had once spoken to Sushant Singh Rajput on the phone when the Padmavat incident occurred, to tell Rajput not to support Bhansali. Apart from that, they’ve never met, though he met Chakraborty once, according to him, at the mortuary. As he explained to Goswami, he apparently went to the mortuary to see Sushant as a fellow Rajput.

Why is Rathore so involved in this case?

“I am a Rajput. I am a member of the Karni Sena. Sushant was also a Rajput, it’s my right to be involved,” Rathore replied.

When he left the mortuary, he said, Aaj Tak spoke to him but the interview never aired. So, Rathore approached Arnab Goswami who helped him “bring the news to the world”. Rathore added that Chakraborty must be arrested “as soon as possible” on the basis of her saying “Sorry, babu” to Rajput’s body.

In his post-Republic days, Rathore spends his time answering “calls from all across the country, mostly from my supporters and from TV channels”. He has a girlfriend but he quickly said, “Woh Rhea jaisi nahi hai.” She is not like Rhea.

Currently, Rathore’s Facebook page, which has over 21,000 followers, is filled with posts seeking justice for Rajput, Rathore’s TV interviews, and pictures from his time in Jaipur. One photo shows him standing on a terrace, arms extended, with the caption: “For success in life...you need two things...Ignorance and confidence...❤️ My Jaipur.”

Politics to the Right

Through the course of my conversations with these men, it became apparent that what irritated them the most was Chakraboty’s alleged infidelity. As men, they seemed to empathise with the pain Rajput might have gone through of loving a “morally corrupt woman”.

Apart from that, the other common thread was their tendency to be aligned with the Right. However, only Dheeraj openly proclaimed his support for the BJP; both Rathore and Chaudhary said this issue isn’t political.

Dheeraj’s affinity towards the Right came forward in our conversation when he asked me if I had worked as a reporter during the citizenship law protests, and what I felt about BJP leader Kapil Mishra’s role. Mishra had made an incendiary speech in February targeting the protesters against the Citizenship Amendment Act, and the Delhi riots followed soon after, leaving over 50 dead.

When I told him that no matter what side I’m on, violence is not the way out, he said, “Violence for religion is justifiable. There are Muslims living in my lane. Tomorrow if they block the road, there is a limit to how long one can wait for the police before taking action himself.”

He also brought up Asifa Bhano, the eight-year-old who was raped and murdered in Jammu in 2018. “Why is that when Asifa, that Muslim child, was raped in a temple in Jammu, all Bollywood celebrities came out and shamed the country?” he said. “What about Hindu women? I am not saying they should not speak about the injustice against Asifa, I’m just saying you cannot internationally shame your country. These celebrities, they are not with us Hindus. They are not with the country.”

Dheeraj, Chaudhary and Rathore all agreed that the only journalists currently doing his job correctly is Arnab Goswami. Dheeraj added that he’s a fan of Zee News’ Sudhir Chaudhary and Aaj Tak’s Anjana Om Kashyap — both of whom are also known for their proclivity towards the BJP.

Lack of moderation of hate content

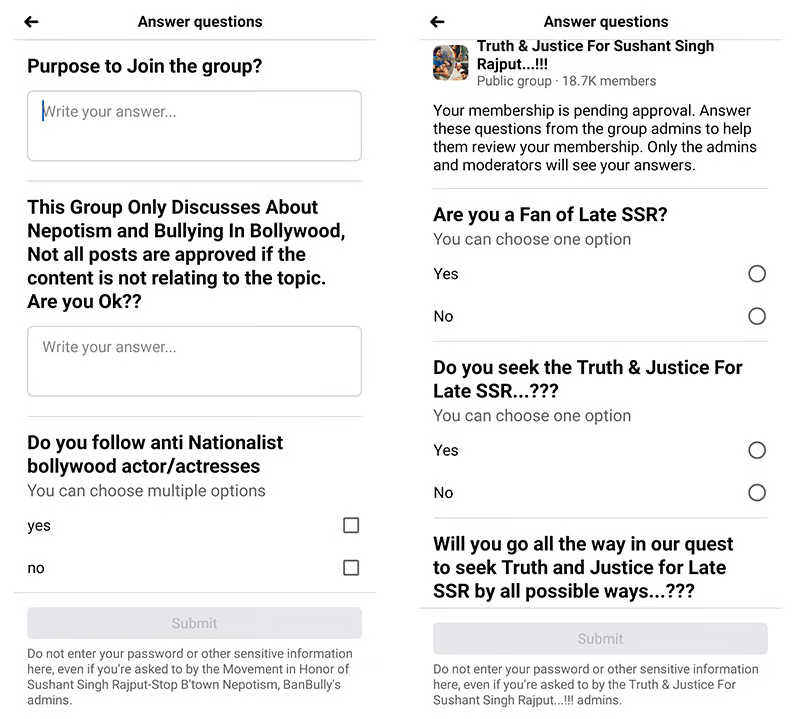

After these chats, I went through 15 Facebook pages dedicated to fighting for “justice” for Rajput, which has now become synonymous with arresting Chakraborty. These pages are managed by 35 admins in total, of which 20 seemed to have authentic profiles on Facebook, three were clearly fake, three were aliases, and nine I couldn’t tell.

I identified fake profiles based on the fact that they had no personal or authentic pictures. The profile images were either pictures of Rajput or representational images, the friends list was limited, and there was no personal information like place of work.

There was no consistent pattern to be established between the profiles, apart from their support for Rajput, love for Goswami, and hate towards Chakraborty. Some had a history of hateful, communal posts, or far-Right posts, some had posts critical of the government, and others had almost no political posts at all.

Here’s a sample of the sort of hate spewed against Chakraborty.

In the background of this venom is the fact that Facebook India has been facing tough questions in recent weeks over its propensity to ignore hate speech. A Wall Street Journal piece reported on Facebook’s soft approach to posts inciting violence by members of the BJP, although the social media giant has robust policies for the same — on paper, at least.

It doesn’t take much to notice that most of the pages I surveyed violate multiple regulations and standards set by Facebook, especially with regards to hate speech, bullying and harassment , and violence and incitement. Nevertheless, most of them have been online for over six weeks, and continue to garner a massive following and rapid engagement.

The news and us

So, let’s return to this question: What does the Sushant Singh Rajput case reveal about us?

It’s a vile but immensely sustainable, and successful, ecosystem, and I reached out to Alt News’ Pratik Sinha to learn more. Alt News has largely kept away from reporting on the news coverage of Rajput’s death.

As Sinha said: “I can bust facts, not gossip.”

News has now entered the realm of gossip, Sinha said, which is rooted in “mudslinging and rumour-mongering”. “Gossip is addictive. I don’t know what to bust in this bizarre case...Initially it looked like this incident was used as a campaign strategy for the upcoming Bihar election, but right now? It has somehow gained a life of its own. Where should one draw the line between freedom of speech and freedom of life?”

Sinha described the viral nature of this “news” as “coordinated inauthentic behaviour”.

A coordinate effort at hate often has two motives, financial or political. In the circus surrounding Rajput’s death, it’s impossible to pinpoint either with clarity. For the many young people involved, Sinha said, being able to earn instant recognition is motive enough.

“For example, maybe for this boy Dheeraj, if not for this case he might not have had women coming up and talking to him,” he said. “Now this may seem frivolous but for him, this must be life-changing.”

What forms a narrative, Sinha explained, is the size of the body that sustains it. Leading channels like Republic and Zee News serve up content that is religiously shared by these Facebook pages. So, who is the trigger: the public, or the news? Has social media ensured that if there’s enough public outrage, news organisations will have to take notice? Or do news channels, in their race for TRPs, produce content tailormade to appeal to the nation’s imagination?

It’s a chicken-and-egg situation, so it’s impossible to accurately answer.

For those without financial or political ambitions, this case seems to have given them a sense of purpose, or “social currency”, as Sinha called it. Dheeraj told me that apart from support, he also receives threats from Shahrukh Khan or Aamir Khan fans. Does that scare him? He immediately and excitedly replied, “No, no, not at all. Maybe it will be good if something big happens with me.”

When it comes to news channels, no matter what came first, media houses ensured that the story stayed alive. In the last month alone, there were four child rapes in New Delhi and a rise in caste- and gender-based violence in Uttar Pradesh. The economy is down, the unemployment rate is up, floods and monsoons have displaced thousands, and the ongoing pandemic claims hundreds of lives every day.

Yet all of this takes a backseat when compared to the Rajput case. Has the case become a distraction from the very real social and cultural fears that we face? As Orwell once said, “Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban.”

On Facebook allowing such content to thrive, Sinha said: “Content moderation is most often a business decision. If you take down a post or page that has over one lakh followers, then it means you lose that many eyeballs, which then means you lose that many people looking at advertisements. And that’s where the money flows in for these platforms. So most often, these policies are only written down, not implemented.”

In the last decade, two media trials stand out: the Aarushi murder case and the death of Sunanda Pushkar. Neither found a satisfying judicial conclusion. Trials by the media don’t happen impulsively, Sinha pointed out. “Every day, we scratch our heads as to what is happening today. But it isn’t like we were fine yesterday or the day before, right?” he said.

And ultimately, no matter the outcome of the investigation into Sushant Singh Rajput’s death, the biggest reveal by the media is what this case has exposed when it comes to our society.

Arnav Binaykia, Anna Priyadarshini and Monica Dhanraj contributed research to this article.