Jhund triumphs but with a flawed depiction of Ambedkarite movement

Manjule’s first mainstream Hindi film gets many things right, but misses out on the political dynamism of Nagpur slums.

A story set in a slum isn't new for commercial Hindi cinema, or Bollywood as it is fondly known. For decades, slums have been where poverty and crime thrive, and where talent lies hidden. These tropes, along with actor Amitabh Bachchan playing a character named Vijay, are practically Bollywood traditions.

Writer-director Nagaraj Manjule makes his Bollywood debut with Jhund, telling a story built on these familiar elements. However, seen through Manjule’s eyes, neither the slum nor its residents feel clichéd. Instead, what we get is a story about discrimination and lost innocence that feels both inspiring and rooted in reality. You’d expect nothing less from the director of the Marathi films Fandry and Sairat, both of which received widespread acclaim for Manjule’s incisive storytelling.

Based on the real-life experience of Vijay Barse, who founded the non-governmental organisation Slum Soccer, Jhund is about a group of young people from a slum area in Nagpur known as Gaddigodam. They catch the eye of sports coach Vijay Borade (played by Amitabh Bachchan) and sport becomes a ray of hope, motivating the slum ‘kids’ to leave behind the world of crime and dream of a better future. In addition to a story and dialogues that are sometimes hilarious and frequently moving, Jhund has excellent cinematography and a fantastic soundtrack.

Manjule, fondly known as Anna, is also the casting director for Jhund and has introduced a cast of non-actors who, like in Fandry and Sairat, impress with their subtle and natural acting performances.

Unlike most depictions of slum kids on film, the soon-to-be footballers of Jhund are not begging for the audience’s sympathy or looking for a saviour. All they want is a fair shot at a better future. The non-actors don’t get credited on the film’s IMDb page, but Ankush Gedam along with characters like Babu and Karthik steal the show.

Alongside the non-actors are familiar faces and experienced actors like Somnath Awaghade, Akash Thosar, Rinku Rajguru and Tanaji Galgande, who appear in small but impactful roles.

There’s a lot to love in Jhund in both its story and its details. For those of us from Nagpur, it’s the first time we’re hearing the Nagpuri accent in Bollywood. However, even though I know the slums of Nagpur, where the film is set, I found it difficult to relate to the world that Manjule showed in his film.

Locating Gaddigodam

Gaddigodam as Manjule shows it in Jhund feels generic. As someone who was born and raised in a slum in Nagpur, I expected to see some of the distinct characters that these neighbourhoods have. Jhund misses out on showing how actively people who live in slums have been involved in the Ambedkarite movement, often throwing up important leaders. To speak of the upliftment of slum dwellers in Nagpur as Jhund does but without talking about the Ambedkarite movement felt like a strange storytelling call by Manjule.

Strangely, there are no Buddha Viharas in any frame of Jhund. The absence was a detail that struck me because there are viharas in Gaddigodam – my parents got married in one of them, in 1985. Neither is there a picture of the Buddha on the banner poster during the scene in which Ambedkar Jayanti is celebrated. In my experience, you can’t have Ambedkar Jayanti celebrations without Buddha and Babasaheb together in a frame.

Buddha Viharas are not important only for their religious value. As director Pa Ranjith showed in Kala, the Buddha Vihara in the backdrop becomes a symbol of revolution. Similarly, Dikshabhoomi, which signifies liberation and plays such an important role in the lives of marginalised castes in India, is depicted as yet another background, with no indication of what the space symbolises to oppressed communities. In the recent past, students from Nagpur slums have been able to attend well-respected universities in India and abroad. Many have returned to places like Gaddigodam to mentor the next generation of slum children and most Buddha Viharas in Nagpur have turned into libraries. This is the kind of detailing that I would have appreciated if I’d seen it in Jhund.

I was also hoping that Manjule, who spent time researching in Nagpur’s slums for Jhund, would have included details and references that distinguish these neighbourhoods.

For instance, while Barse’s efforts have rightly received a lot of attention, Slum Soccer did not introduce football to Nagpur’s slums. There’s a long tradition of football being played in these neighbourhoods and it has even been written about by Wamanrao Godbole.

Godbole was a close associate of Dr BR Ambedkar, and in his book Dhammadikshecha Itihas (published by Sugat Prakashan), Godbole mentioned that in 1942, there was already a football club named Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar Football Club in a slum near Buldi in central Nagpur that is about three kilometres from Gaddigodam. He also mentions 20-30 children from Maharpura playing football on a ground in Buldi.

Ideology and politics in everyday life

Manjule doesn’t hide his Phule-Ambedkarite politics in Jhund. His characters greet each other with “Jai Bhim” and icons of Maharashtra’s anti-caste movement are seen repeatedly. Still, I found myself wishing Manjule had found ways to include references to the rich political history. For example, Jhund doesn’t mention the Samata Sainik Dal, which was founded by Dr Ambedkar in 1924 and has a rich history of activism.

In 1942, under Dr Ambedkar’s leadership, a meeting was held near Gaddigodam. An article published in 1998, in Samata Prakashan, said thousands of women from various slums of Nagpur attended the meeting, which is an indication of how politically aware and active these communities were. Yet there is little reflection of this legacy in Jhund.

While shooting a documentary film, I met activists like Bhau Lokhande who recalled Dr Ambedkar’s visit to Nagpur’s Laksharibaug in 1954. People spoke of how Dr Ambedkar sat and had discussions with locals in Nagpur slums and about one particularly at the Golbazar in Goddigodam. The oral history shows how everyday people and their lives were impacted by Babasaheb’s ideology.

In Jhund, we see photo frames and cut-outs with the faces of icons, but the film doesn’t directly talk about the importance of the Ambedkarite movement in these slums.

An example of how this could be depicted is in Jayanti, directed by Shailesh Narwade, which shows both those who party hard on Ambedkar Jayanti and those who are inspired by Ambedkar’s famous slogan, “Educate, Agitate, Organise”.

Stumbling blocks

Occasionally, Jhund seems to fall back on stereotypes, which is disappointing coming from Manjule, who is known for his nuanced characterisation.

At one point, a construction labourer says he can only do the back-breaking labour required of him when he’s drunk, which sounds similar to testimonies of manual scavengers but doesn’t sound credible for someone working in construction. It’s as though Manjule is suggesting the experiences of all these marginalised workers is the same.

There’s another instance where one of the slum kids comes to play football, wearing a sherwani – even though they’ve been watching students play on that ground from over the wall. It’s played for laughs, but the characterisation is a hat tip to the old trope of mocking the underprivileged for not knowing what is considered appropriate and assuming poverty leads to a lack of common sense.

The women characters in the film are also depicted on the basis of the trope that all upper caste and upper class women have fair complexions. Also, it seems if you can afford to drive a Mercedes car, then you can drive about 16 hours at a stretch while keeping your make-up pristine.

While Jhund may not have women characters as fiery as Rajguru’s Aarchi in Sairat, it does have Raziya (played by Rajiya Kazi), who displays courage when she leaves a toxic marriage and follows her dream.

Rajguru has a small role in Jhund as an adivasi girl and through the story of her character, Manjule brings the tribal language Gondi into a mainstream Bollywood film. It’s a bold move of language assertion.

While Rajguru did a great job speaking Gondi and playing the adivasi character, her father mysteriously goes from speaking only Gondi to becoming proficient in Hindi. He’s not the only one who gets the short end of the characterisation stick. From Borade’s own daughter to the token tomboy among the female footballers, the crowded cast of characters in Jhund means too many of them don’t get enough attention from the script despite the film’s running time being four minutes short of three hours.

Flawed but triumphant

Jhund has the most Bollywood masala of all of Manjule’s films so far and that comes with its benefits and drawbacks. It feels formulaic and generic at times. There are many conflicts, but little tension or suspense. On the other hand, when the formulae work, Jhund crackles with energetic performances and the portrait of class and caste divide is painted with great emotional depth.

While some themes and characters aren’t explored enough, there is an undeniable triumph in Manjule bringing to the big, Bollywood screen a scene in which Bachchan pays his respects to Dr B R Ambedkar. In a country and industry that is dominated by majoritarian casteists, this proud assertion of Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi culture and identity is a significant act of courage.

The film succeeds in its depiction of caste and class divides. One of the most powerful scenes comes towards the end, when the slum children, sitting in a plane, fly over a wall painted that has the warning “Crossing the wall is strictly prohibited” written on it.

It’s a scene that celebrates the grit of the underprivileged and those whose merit is marginalised because they were born into oppressed communities. For them, Jhund is an inspiration to to open their wings and fly so high that no wall — of caste or class or any other hierarchy — can stop them.

The writer is an independent journalist based in Navi Mumbai.

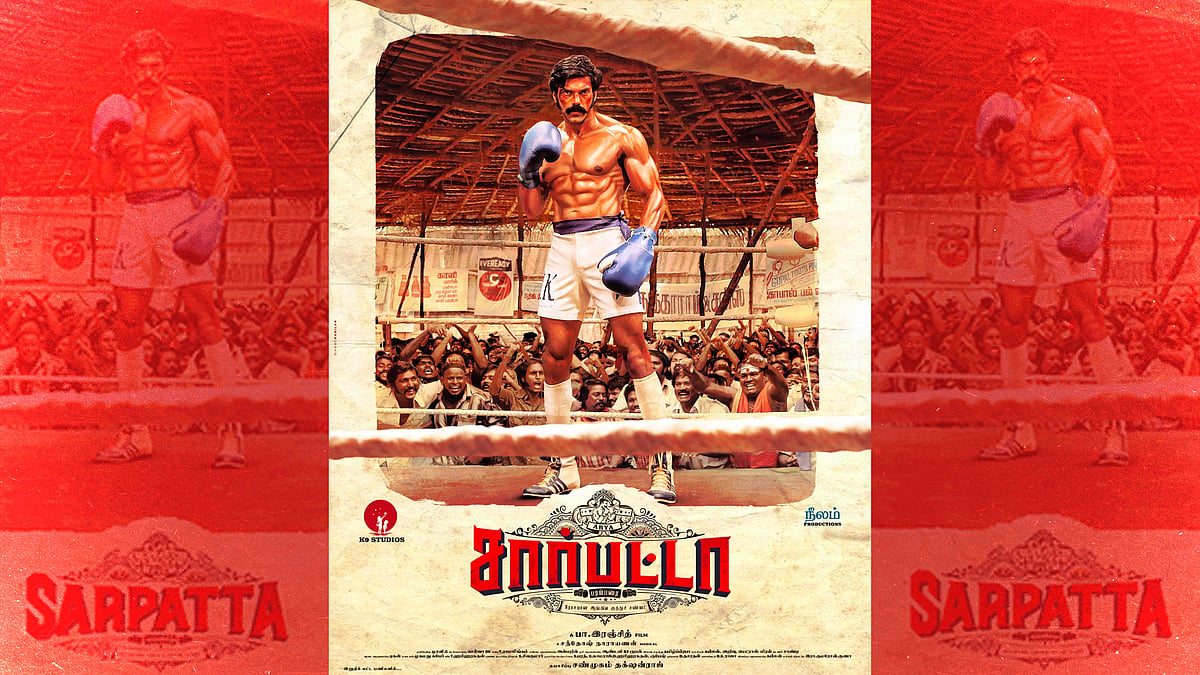

Sarpatta Parambarai: Pa Ranjith continues his quest to smash stereotypes

Sarpatta Parambarai: Pa Ranjith continues his quest to smash stereotypes

Christopher Nolan’s 'Tenet' is disappointing. But it’s great for cinema

Christopher Nolan’s 'Tenet' is disappointing. But it’s great for cinema

NL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.