Tamil Nadu’s ‘attacks’ on migrants: The anatomy of a rumour

And what the BJP hoped to gain – but didn’t.

A friend sends a text message: “My mother’s really worried about the murders of Bihari workers in Tamil Nadu, she saw some videos on WhatsApp.”

A journalist posts on a private social media group: “Can someone verify whether workers from the Northeast are at risk in Tamil Nadu too? I got a video warning them.”

Someone’s parent says bitterly: “This is what happens under these governments that hate North Indians.”

In the wondrous times of the internet, it takes zero effort for a lie to become the truth. That’s how it played out in Tamil Nadu last week.

Videos of events were passed off as North Indian migrants being “attacked” in the state. For instance, one video was of two men stabbing a lawyer in Rajasthan, another showed a man being murdered in Telangana. A third was of a murder in Karnataka, and a fourth of a Tamil man hacked to death in Coimbatore.

In all these cases, the captions on social media indicated that these were “attacks” on Hindi-speaking migrants in Tamil Nadu.

In the textile town of Tirupur, a migrant worker’s body was found on the train tracks, leading to hundreds of workers congregating in protest. The police had to release CCTV footage – showing the man walking along the tracks and being hit by a train – to prove this wasn’t a case of “murder”.

Sections of the media contributed to the chaos. Dainik Bhaskar was arguably the trigger for widespread reportage on these purported attacks, alleging at least 12 “murders”. The stories were quickly picked up by C-grade enterprises like OpIndia which alleged “Talibani style attacks” on migrant workers.

Meanwhile, fact-checkers, journalists, industrialists and representatives from the police and government worked overtime to clarify that all was well.

While much has been written and analysed about the nature of these falsehoods, what’s interesting is the reaction of the BJP.

Different strokes

In Bihar, the party tweeted that workers had been “killed” and attacked the RJD-JDU government for not acting. In the assembly, BJP MLAs demanded chief minister Nitish Kumar’s resignation and criticised deputy chief minister Tejashwi Yadav for “eating cake” while his Bihari brethren were dying.

For context, Yadav had on March 1 attended a programme in Chennai on the occasion of chief minister MK Stalin’s 70th birthday. Alongside Akhilesh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party, Farooq Abdullah of the National Conference, and Mallikarjun Kharge of the Congress, they pledged to take on the BJP in 2024.

Fact-finding teams from Bihar and Jharkhand later visited Tamil Nadu to meet with officials and workers.

Next, in Uttar Pradesh, BJP spokesperson Prashant Patel Umrao tweeted a photo of Yadav with Stalin and alleged 12 Bihari workers in Tamil Nadu had been “hanged to death”. He was booked in Tamil Nadu for fake news. Umrao approached the Delhi High Court saying he had fallen prey to fake news and was granted transit anticipatory bail for 10 days.

But in Tamil Nadu, the BJP took a completely different tack.

MLA Vanathi Srinivasan accused a “few organisations of sowing hatred” and urged the DMK government to book those responsible under the National Security Act.

On his part, BJP chief K Annamalai said “fake news” about migrant workers was being spread and that it was the DMK’s fault for creating a “divide”. After all, didn’t Stalin’s son Udhayanidhi once wear a t-shirt saying Hindi Teriyadhu Poda while Stalin’s sister Kanimozhi grumbled about airport security speaking to her in Hindi?

“They were the ones who started the venomous campaign, against North Indians,” he wrote on social media, “and it makes us think that they could be the reasons for the current rumours against the guest workers.” He was promptly booked for promoting enmity and disharmony.

Annamalai’s approach isn’t surprising. The BJP in Tamil Nadu walks a line that’s often forced to deviate from the national one. It defends Tamil identity and describes itself as being “allergic” to Hindi imposition. Its only major ally, the AIADMK, has panned the BJP’s pet projects like NEET and the Citizenship Amendment Act. The BJP was also caught between the AIADMK’s splitting into two in the battle between E Palaniswami and O Panneerselvam, finally throwing its weight behind EPS.

And Annamalai has his own internal woes to deal with.

Internal strife

Two days ago, BJP state IT cell president CTR Nirmal Kumar resigned, saying the state leadership conducts “surveillance” on functionaries, works against party interests, and uses the party for “commercial means”. He then joined the AIADMK.

A day later, IT cell secretary Dilip Kannan also quit. Like Nirmal, he squarely blamed Annamalai for leaving and then joined the AIADMK.

Annamalai then lashed out at his alliance partner for accepting the BJP’s former members. “If I go shopping,” he told India Today, “my shopping list will be big.”

Months before, another rift had unfolded within the party over an audio leak of a conversation between two party members – OBC Morcha state general secretary Surya Siva and minority wing leader Daisy Saran. The state BJP suspended them for a period of six months.

It also suspended actor Gayathri Raghuram, who had joined the party in 2014, after she slammed Surya on Twitter and said it was a mistake to give a state post to “such hyenas”. She then quit the BJP in January, saying “women are not safe” under Annamalai. She called him a “cheap tactic liar and adharmic leader”, and said she was “ready to raise a police complaint”.

Annamalai, a former IPS officer, had joined the party in 2020. He contested in the assembly election in May 2021 from Aravakurichi but lost. Two months later, he was appointed the president of the BJP Tamil Nadu after former chief L Murugan was sworn in as a minister of state in the Lok Sabha. He was only 37 years old at the time and perhaps the idea was to project him as the true “youth leader”, a sobriquet once held by MK Stalin.

After all, the BJP’s inroads in Tamil Nadu have been slow going.

In the 2019 Lok Sabha poll, The BJP lost its only seat in Kanyakumari and its vote share fell from 2014’s 5.56 percent to 3.66 percent. In the 2021 assembly poll, it won four seats and entered the legislative assembly for the first time since 2001, albeit in an alliance with the AIADMK, the primary opposition party. It is still a minor party though Delhi media treats it as a key member of the opposition.

So, the migrant rumours of this week presented Annamalai’s BJP with the opportunity to tackle the DMK government on a particularly thorny issue – conflating the DMK’s “anti Hindi” stand with being “anti North India”.

In Tamil Nadu, Hindi imposition is an intensely political and personal issue, and has been since the 1930s, when Periyar and the Justice Party led demonstrations against C Rajagopalachari’s Congress government. Former Tamil Nadu chief minister CN Annadurai once criticised the idea that Tamils had to study Hindi for a larger communication with India, reportedly saying: “Do we need a big door for the big dog and a small door for the small dog? I say, let the small dog use the big door too.”

These politics were resurrected under the BJP government in the centre. In October 2022, the Tamil Nadu government adopted a resolution against the central government’s attempts to impose Hindi.

The BJP had staged a walkout at the time, but perhaps saw the migrant rumours of this week as a way to revive the issue. But instead, with a flurry of clarifications and FIRs, public attention has been drawn to the fact that the entire controversy was engineered.

Not quite the outcome the BJP would hope for.

Tamil Nadu finance minister explains why he won’t listen to Modi on ‘freebies’

Tamil Nadu finance minister explains why he won’t listen to Modi on ‘freebies’

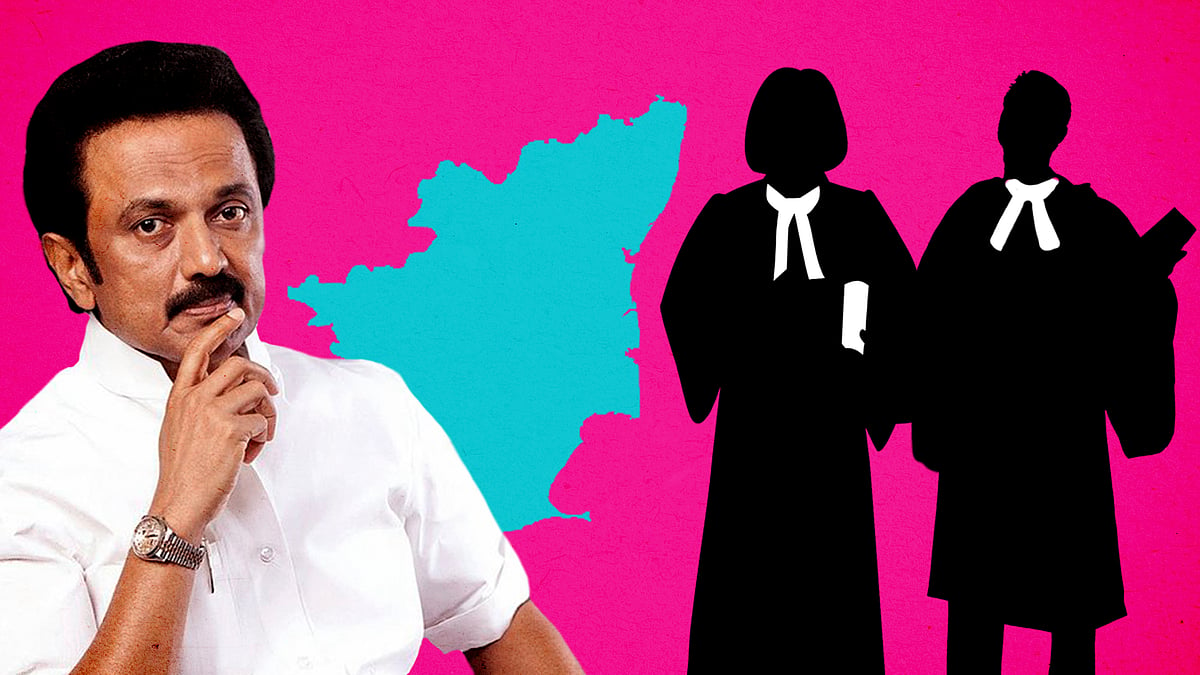

With the largest legal wing in Tamil Nadu, why DMK banks on it to get things done

With the largest legal wing in Tamil Nadu, why DMK banks on it to get things doneNL Digest

A weekly guide to the best of our stories from our editors and reporters. Note: Skip if you're a subscriber. All subscribers get a weekly, subscriber-only newsletter by default.